A False Farewell: Writing as Resistance to a Transfer to the AP Photo Desk in New York

GRUMPY OLD VIETNAM HAND.

By mid-1974, the cease-fire in South Vietnam held - at least on paper. But no one really knew what would come next. In Washington, Congress was slashing aid and by August, President Thieu’s strongest ally Nixon was gone. I was still in Saigon, six years into a locally-hired post with the AP, and now called back to that damned photo desk in New York by early ‘75. I began the motions of farewell: another R&R with the family, a final swing up into Laos, and starting adoption paperwork for Kim-Dung’s niece. But I wasn’t ready to let go. I was still writing - stories beyond the lens, entangled in a war and a country that had been my home for more than a decade, one I couldn’t simply leave behind.

After all those years, we were running out of places to R&R, but we decided to head back to Bangkok and perhaps Vientiane, and this time take the kids along, especially as Laura was still recovering from a debilitating bout of haemorrhagic fever. But the R&R quickly turned into our worst ever, as Kim-Dung was hospitalised with badly infected cysts in each armpit, which required surgery at the Bangkok Nursing Home. That two weeks was the longest I’d ever spent in the Thai capital, and I came away hating its atrocious weather, horrible expense, endless traffic jams and super-cold air conditioning.

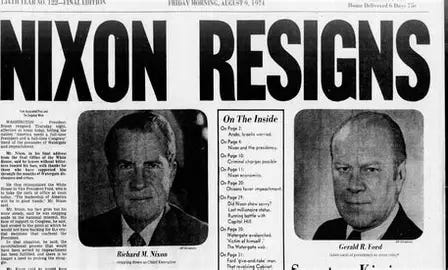

Lots more was happening back in the US in early August 1974, as the Congress limited annual military aid to South Vietnam to $1 billion, down from $2.8 billion the year before. A few days later that was reduced to $700 million, and then only $300 million in 1975. Although much has been made of this dramatic cut over the decades, I supported not giving President Nguyen Van Thieu any more for ‘his bloody war-making machine’, as I called it in one letter. The bastard should free his political prisoners and form that coalition government. Simple.

Coming on top of deep Congressional cuts to military aid, President Richard Nixon’s August 1974 resignation dealt a severe blow to the Saigon regime. President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu had been secretly promised U.S. military intervention if the North violated the 1973 Paris Cease-Fire - concessions made to secure South Vietnam’s assent. As we shall see, it didn’t take long for Hanoi to put that promise - and Washington’s resolve - to the test.

After being hounded for months over the Watergate affair, and now having been impeached by the US House of Representatives, President Richard Nixon dramatically resigned on 9 August. I gloated over his demise, and even welcomed his replacement, Gerald Ford, as a breath of fresh air.

But the Communists were already testing the post-Nixon waters with a ‘limited phased offensive’, although no one yet expected anything full-scale. ‘I think the other side is being very careful not to provoke an incident which would touch off any sort of US reaction, such as renewed bombing,’ I told my folks.

When we got home to Saigon, the kids were totally absorbed by a Mother Goose book my folks had sent Alexander for his third birthday, and which he carried around everywhere, even to bed. When I got home at a reasonable hour I’d read them a few stories, hoping to make them drowsy, but they’d scream for more.

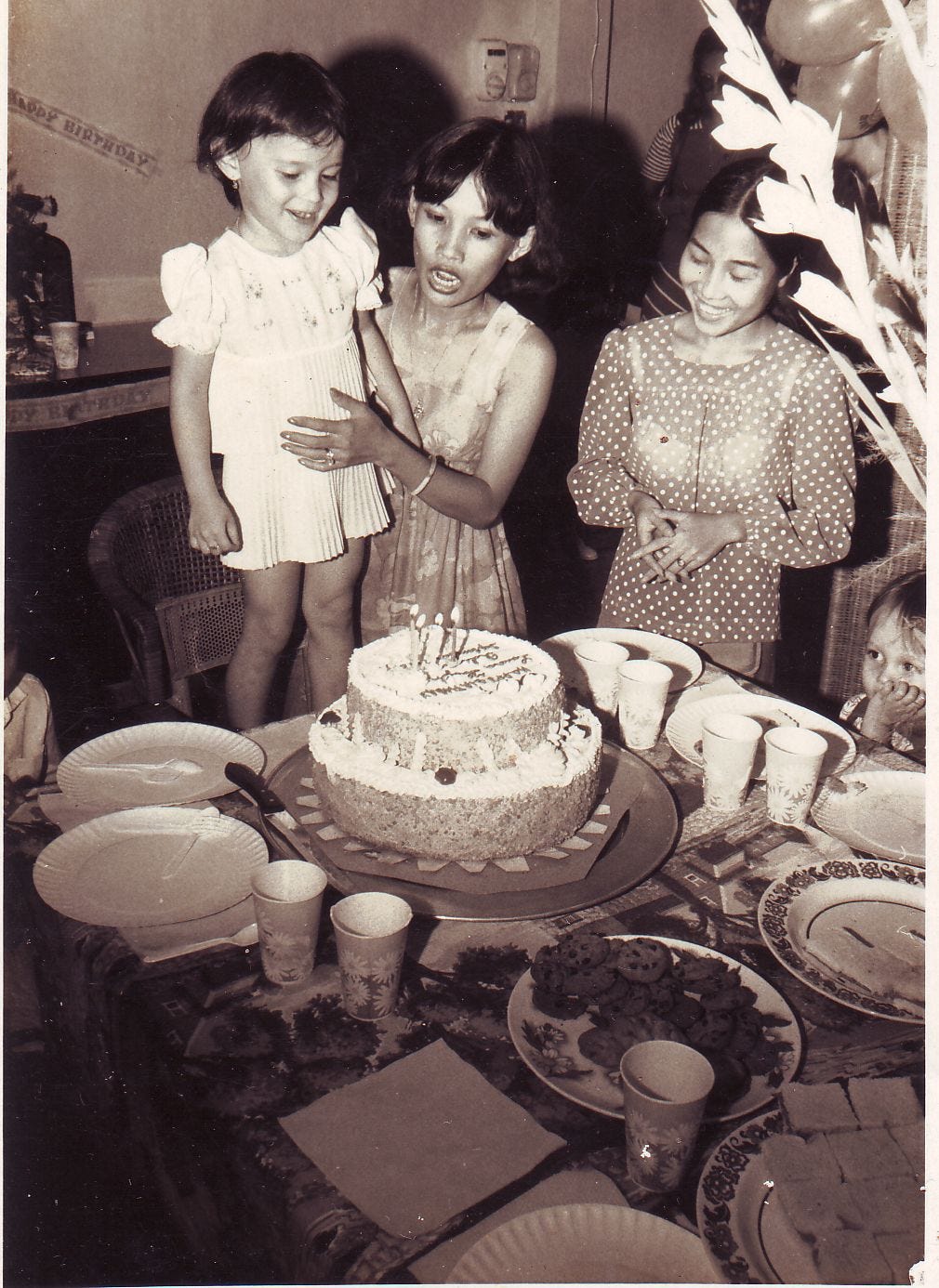

Our daughter Laura turned five in September 1974, here with her mother Kim-Dung and her best friend Mai.

Now nearly five, Laura was going through a ‘why?’ phase, and demanded explanations: why were all those kids in a shoe, why were there so many, why was there no daddy around. Alexander was going through a bad stage, grumpy in the morning like me, and made to stand in a corner for not saying sorry to his mom. But the children were my greatest joy.

Through Bureau Chief George Esper, I’d been negotiating my future with New York for months. I wanted a written agreement of another foreign assignment, but AP wouldn’t commit. Their main concern was that Saigon was overstaffed, and they wanted me on that photo desk in New York by February 1975.

Horst Faas, who was now in London, assured me I’d move on to Europe within a year or so, so I agreed, and with mixed feelings began my farewells to Vietnam. ‘I’ve gotten just about all the “experience” I can out of this stint and it’s time to move on to other, but not necessarily better, things,’ I wrote my folks. We also began work on adopting Kim-Dung’s young and born-out-of-wedlock niece, Phuong, who was living with the family down in Go Cong.

Despite New York’s determination to bring me back as a photo editor, I was still mostly writing. I was doing ‘bleeding heart’ stories like the begging girl in the C-ration box on Tu Do Street, who was heading to Houston for an operation on her congenital heart problem. A single woman from Denver who wanted to adopt a couple of Vietnamese orphans.

I also wrote about how South Vietnam’s economy, and certainly its infrastructure of roads, ports and airports, was in remarkably good shape, and the country self-sufficient in rice once again. I was pleading, in effect, for more economic aid and investment.

The black market had virtually disappeared, and we now changed our money legally at the Chase Manhattan Bank. And while I couldn’t write it in so many words, I hoped that the combination of a viable neutralist government and foreign aid and investment could see South Vietnam survive.

With world oil prices continuing to rise, and in desperate hopes of getting more Americans onside, the Saigon government was pushing itself as a possible oil producer. So in one my oddest ever assignments in Vietnam, I flew by civilian helicopter out to a floating exploration rig in the South China Sea off the northern Mekong Delta, where I spent several sickening hours bobbing up and down like a cork.

The American explorers had picked up a few positive whiffs of petroleum, and my story pointed to Vietnam’s possible entry into the game, even though its full potential, especially in gas, would only be reached post-war – and then thanks to the Soviet Union.

A Farewell to Laos.

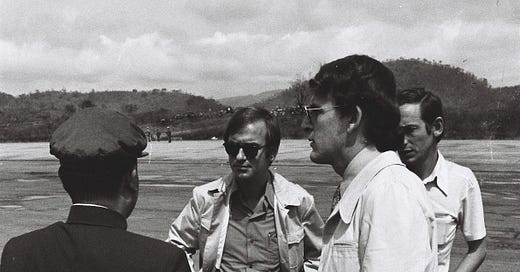

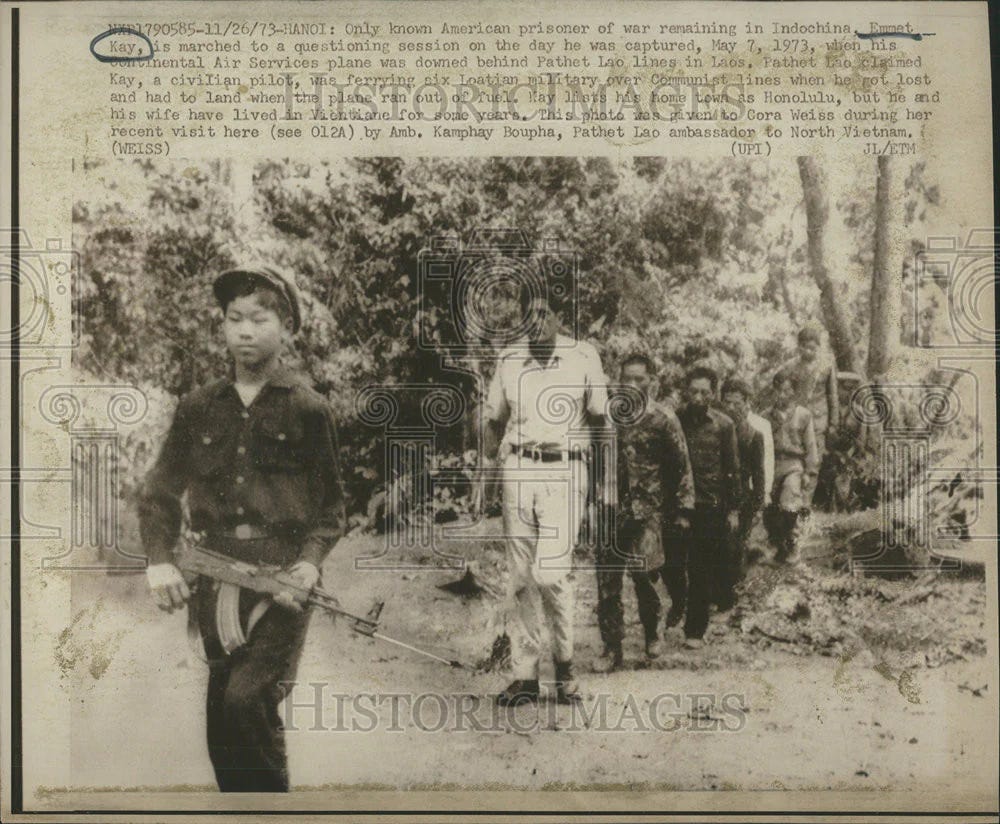

I headed back up to Laos, this time to cover the release of supposedly ‘the last American POW in Indochina’, pushing and shoving with other photographers and cameramen at Vientiane airport as a civilian pilot with Continental Air Services on contract to the CIA, Emmet James Kay, was released.

He’d actually been shot down in May 1973, after the country’s ceasefire, and so had only been briefly held, but other than a handful released in Hanoi, most US military pilots shot down over Laos were killed, or captured and then executed, by the Pathet Lao. With my scheduled transfer to New York now only months away, this was my farewell to Laos.

After Kay’s release, the highlight was a one-day trip up to the famed Plain of Jars for a very odd prisoner exchange that illustrated just how much of a proxy war Laos had been. North Vietnamese POWs were heading back to Hanoi, having been swapped for Thai Army volunteers funded by the CIA.

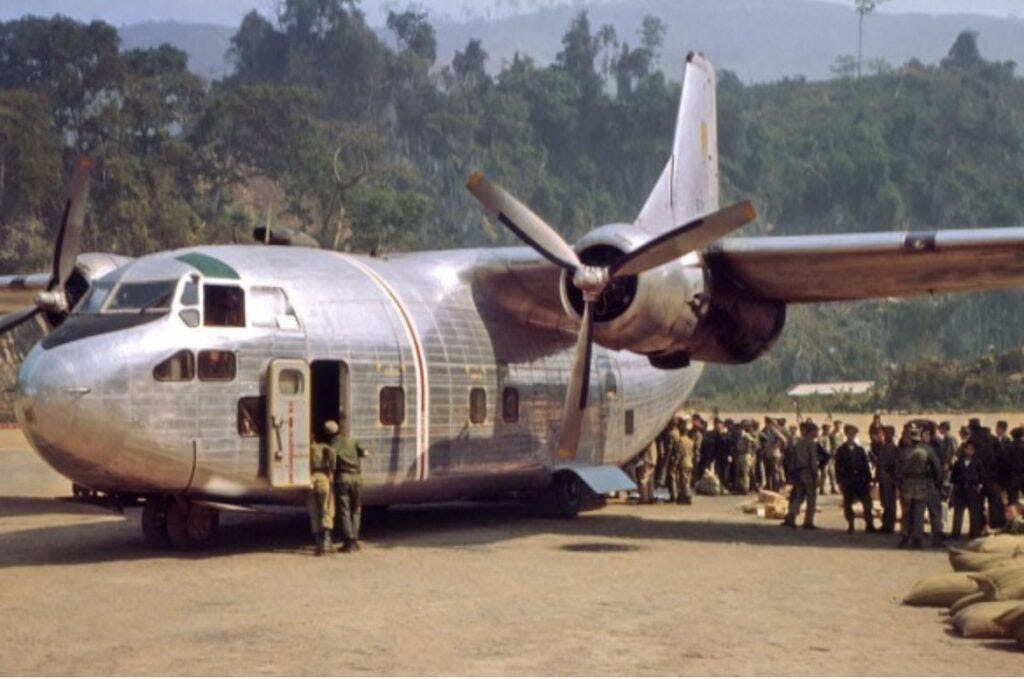

As our Air America C-123 landed on the high plateau’s dirt airstrip, I was reminded of the Katanga’s savannah country of grasslands and rolling hills in then-Belgian Congo, but here were long scars from B-52 strikes, and disfigured hilltops of Royal Lao firebases overrun when the NVA and Pathet Lao occupied the Plain of Jars in 1972.

As at those post-ceasefire POW releases in South Vietnam in early 1973, the NVA tossed off their prison uniforms and hauled out flags, banners and chants, no doubt to make a good impression on their political cadre and explain their captures back home. More subdued, and seeming like overgrown schoolboys in brand-new white shirts, blue pants, caps and knapsacks, the Thais were meekly heading back to their modern world.

Before we could leave, all the released POWs pitched in to push and shove our bogged C-123 out of a muddy bomb crater on the strip. That harmonious moment provided the lede for my story, but I lost play to UPI’s piece about a released Thai POW who had supposedly sighted a US POW during his captivity, a story I discounted.

Hopes for a Political Change in South Vietnam.

Back in Saigon, things were finally happening on the political front with the rise of what became known as the Anti-Corruption Movement, led by President Thieu’s staunchest long-time supporters, the anti-communist Catholics.

Thieu had converted from Buddhism to his wife’s Catholicism, but was never overt about his religion. Recently he’d been cultivating the Confucian emperor ethos, with the revival and celebration of Vietnam’s legendary Bronze Age founders, the Hung Kings.

At rallies all around southern Vietnam, Catholics turned dramatically against Thieu, accusing him and his family, plus his crony generals and officials, of corruption, and demanding immediate change. At first Thieu left them alone, no doubt worried about further cuts in US aid, and still uncertain after losing his arch-supporter, Nixon.

But as they were joined by other dissidents, including the Third Force, and now openly called for his resignation, the repression began as Thieu brought out his brown-camouflaged tear-gas-firing riot police once again. With the presidential palace sealed off with concertina wire, many demonstrations took place in front of the National Assembly building, Saigon’s old Opera House, below our office, so we could sit and watch the scene over a coffee at Givral’s.

When secret policemen grabbed and beat up AP’s Neal Ulevich and CBS correspondent Peter Collins one day, I jokingly said, ‘Well, there goes another $100 million in American aid.’ The government immediately apologised and promised not to do it again.

After the doldrums of earlier in the year, I felt great busy again in Saigon. The endless ceasefire violations and actual battles out there were the stuff of South Vietnamese military communiques, plus the odd comment from the Communist delegations out at Camp Davis. As ever, Saigon’s High Command didn’t want journalists out covering the fighting, and what was left of the press corps didn’t push things. US sources fed most war stories now.

But we really had taken our eyes off the ball. No one was paying close attention to South Vietnam’s ‘million-man army’, and part of the corruption story was how many ‘phantom troops’ that included – just names on the payroll, with Thieu’s cronies pocketing their pay. Things were much worse than we could imagine. And we certainly weren’t putting two and two together over the drastic cutbacks in US military aid by Congress.

Soon I was back on the beat, interviewing and becoming close to the Catholic dissident movement, particularly the Redemptionist Father Chan Tin, a gentle French-speaking priest whose church became a regular stop on my political rounds. I didn’t trust the phones and relied on face-to-face contact.

The Reluctant Prophet - Father Chân Tín

Redemptorist priest and theologian, Father Stêphanô Chân Tín, stood at the heart of South Vietnam’s anti-corruption and pro-democracy movement which burst out in 1974. A soft-spoken intellectual fluent in French and Latin, he led with conscience, not bluster. Through Đối Diện (Face to Face), a Catholic monthly he co-founded, Father Chân Tín exposed torture, political repression, and the regime’s hypocrisy - earning him arrests under President Thiệu and surveillance by the Communists after 1975.

Unlike many clergy, he chose to stay in Vietnam post-war. For his courage, he was placed under house arrest, stripped of his rights, and exiled to remote Cần Giờ. Still, he kept writing - sermons, essays, and samizdat - quietly insisting on the rights enshrined in the very constitution the government claimed to uphold.

At his funeral in December 2012, thousands gathered at Our Lady of Perpetual Help in today’s Ho Chi Minh City. The crowd was thick with the quietly defiant: Catholics, old dissidents, and those who remembered Đối Diện as more than a magazine. It was a farewell not just to a priest, but to a moral compass. He died as he lived - unafraid to speak, even if only in a whisper, and I was privileged to know him.

Long discouraged, my Third Force friends were heartened by the burgeoning Anti-Corruption Movement. But other than a cabinet shake-up and sacking his nephew as a press secretary, Thieu’s changes were only cosmetic. And as violent rioting by thousands of protesters broke out in Saigon near the end of 1974, his repressive image was hardly conducive to any further help from the new administration of President Gerald Ford, which was distracted by rampaging inflation at home.

I was also trying to get my head around moving to New York in the new year. I’d heard depressing tales of difficulty we’d face just finding a place to live in the city. What would we do about school for the kids? They were both attending a nearby Montessori school; Laura particularly enjoyed drawing, where she showed some of her dad’s artistic flair. But Alexander was almost impossible to get moving in the morning, kicking and screaming as the maid took them off to school. They both loved books and their English was coming along well.