Ambush in Phnom Penh: Diplomats, Dope, and the Dark Side of the Moon

GRUMPY OLD VIETNAM HAND.

Before Phnom Penh fell, there were nights that felt almost enchanted - and then suddenly weren’t. I was back in Phnom Penh - not quite late 1974, but past the midpoint of the year, past the point of pretending things might hold. What followed was perhaps my strangest assignment yet: a ceasefire of the personal kind, a diplomatic confession that could have come from a le Carré novel, and a poolside party that turned into a very different kind of ambush.

But what happened to my dear Kim-Dung is also one of my favourite - and strangest - stories from those long years between 1964 to 1975 around the old French Indochina as excerpts from the penultimate chapter of The Bite of the Lotus: an intimate memoir of the Vietnam War continue:

After I took a couple more weeks off, AP Bureau Chief George Esper and I sat down for a long chat. I told him that his temper tantrums were making the office atmosphere too tense, and how I’d prefer to talk things over rather than receive endless memos. He accepted my remarks, but only time would tell. The rainy season was here, bringing beautiful days of billowing tropical cloud formations crowded across the sky. It was time to snap out of my month-long depression.

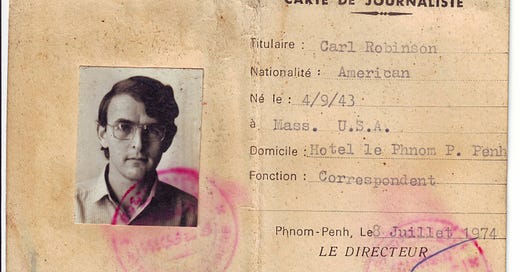

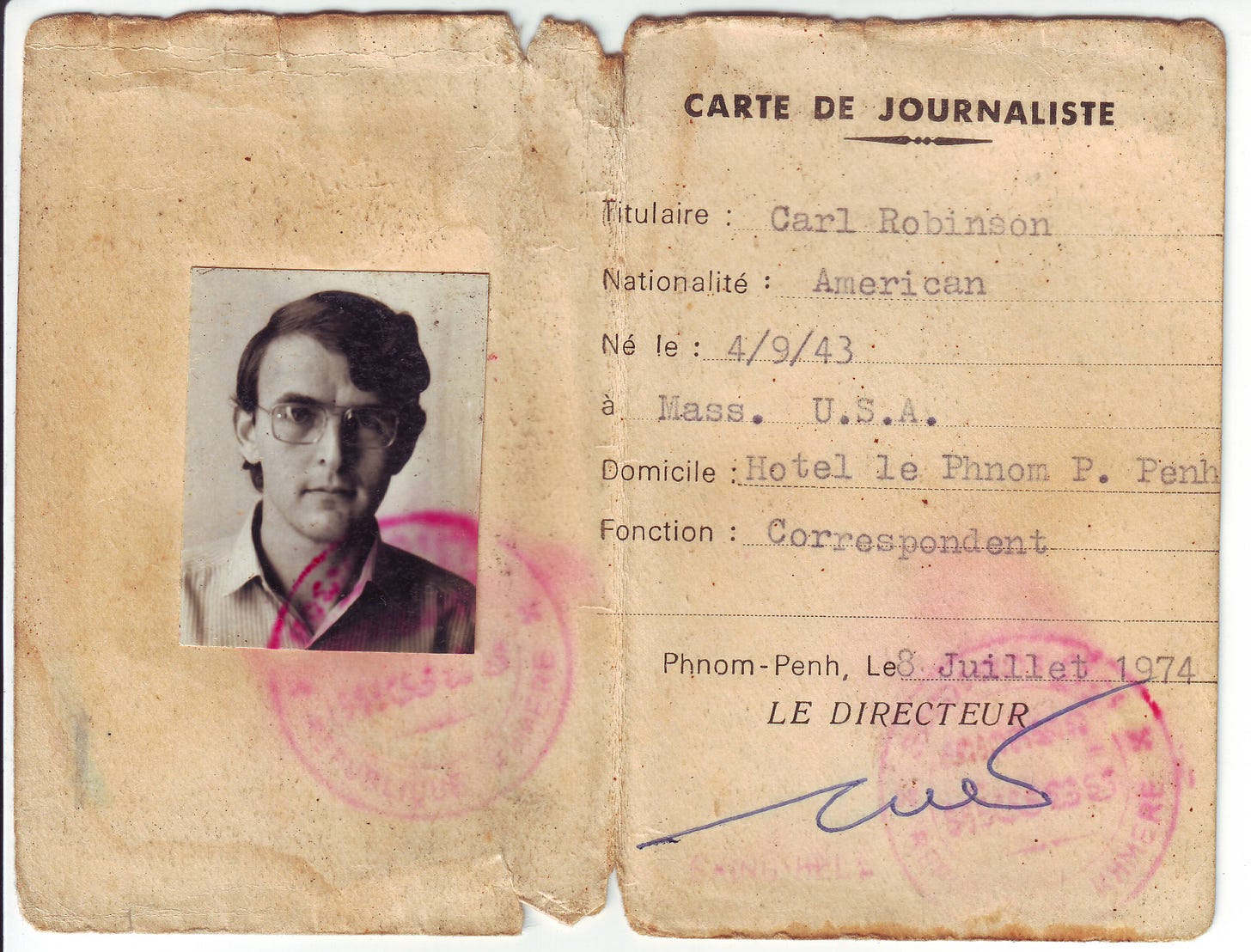

And now, going into late 1974, I was back on the road again for a five-week stint over in Cambodia. There had been student riots in which two government officials were killed, a government crisis occurred and new cabinet formed, meaning day-to-day war stories and even a plane crash. But all the writing also renewed my frustrations over my future with AP.

As I was heading over to Phnom Penh, I told George that I was planning to bring Kim-Dung and the kids for a few days. The city was not so much under siege as ‘beleaguered’, as we clichéd in our stories, and I didn’t consider their visit all that dangerous, even with the mad dash from the airport into town to avoid incoming artillery and rocket fire. I’d show them around the city, enjoy some good restaurant meals and spend time in Le Phnom’s swimming pool with Laura and Alexander. He wasn’t too happy with that idea, but agreed to my bringing Kim-Dung over for a few days.

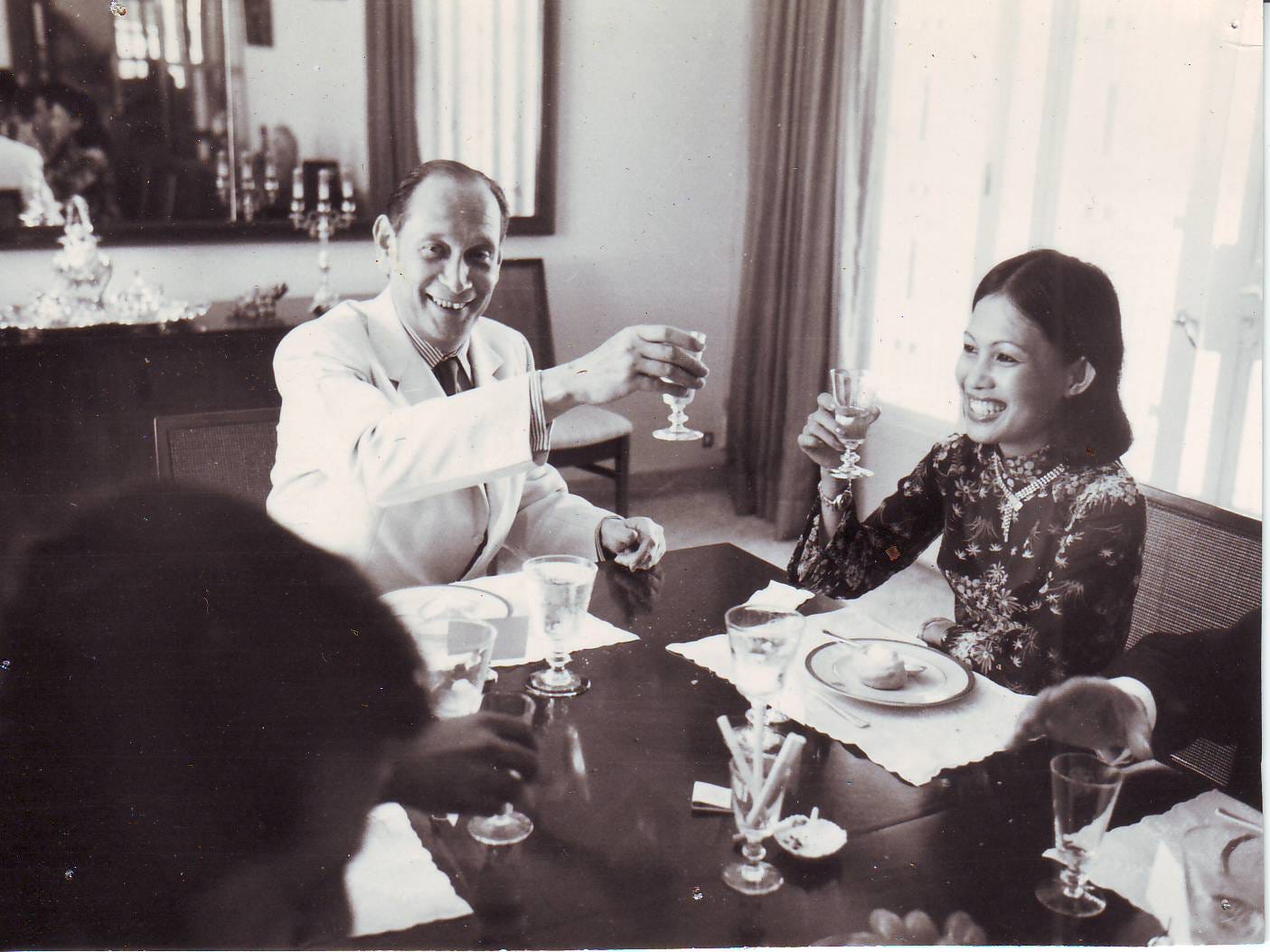

I was looking forward to her joining me in Phnom Penh and, after a frenetic couple weeks down at Chantal’s opium den, I declared a smoking ceasefire of my own and went straight for the duration of her visit. I warned everyone not to say a word about my bad smoking habits, and they were all very welcoming and hospitable, including a formal luncheon and a swim over at new US ambassador John Gunther Dean’s residence. And he definitely wasn’t an opium smoker.

My wife Kim-Dung with US Ambassador John Gunther Dean to Cambodia during her visit over to a ‘beleaguered’ Phnom Penh in 1974. A true gentleman who truly felt the feelings of the Cambodians and heart-broken by the tragedy to come.

The Ambassador Who Wept.

John Gunther Dean arrived in Phnom Penh in April 1974, just as Cambodia’s unravelling entered its final act. A German-born Jew who’d fled the Nazis as a child, Dean brought a moral clarity and emotional depth to the role that was rare in Cold War diplomacy. Unlike his predecessor, Thomas Enders - whose technocratic detachment and Kissingerian pragmatism had left many journalists and Cambodians cold - Dean was deeply invested in the fate of the country and its people. (See my personal anecdote in this earlier Substack.)

When the U.S. evacuated Phnom Penh in April 1975, Dean was seen clutching the embassy’s American flag in a plastic bag as he boarded a helicopter. He later described that day as one of the most tragic of his life: “We’d accepted responsibility for Cambodia and then walked out without fulfilling our promise. That’s the worst thing a country can do. And I cried because I knew what was going to happen.”

The Killing Fields of the Khmer Rouge.

And until his death in 2019, Dean remained haunted by the fall of Cambodia and the horrors that followed.

Among my regular companions down at Chantal’s was the Malaysian chargé d’affaires, in effect the acting ambassador, a man named Ranji, and a first secretary from the French embassy named Jean-Louis. The Indo-Malay Ranji was married to a French woman and, when I dropped by his rambling and comfortable villa one afternoon, he made a strange and tearful confession. While on his previous assignment, in Moscow, Ranji was caught in a relationship with a Russian woman, and then blackmailed to work for the KGB – the classic honeypot – and he was now living in torment.

I didn’t know what to say. Was he just pulling my leg? I never was able to draw him out on the subject again. Interestingly, the Soviets kept their mission in Phnom Penh through the entire 1970–75 period, and even had correspondents covering our side of the Cambodian War.

Just after Kim-Dung arrived, I overheard that Ranji was hosting a big curry party, to which everyone was invited – but not me. When I pressed him, Ranji hesitated a moment and then said, ‘Yes, come along.’

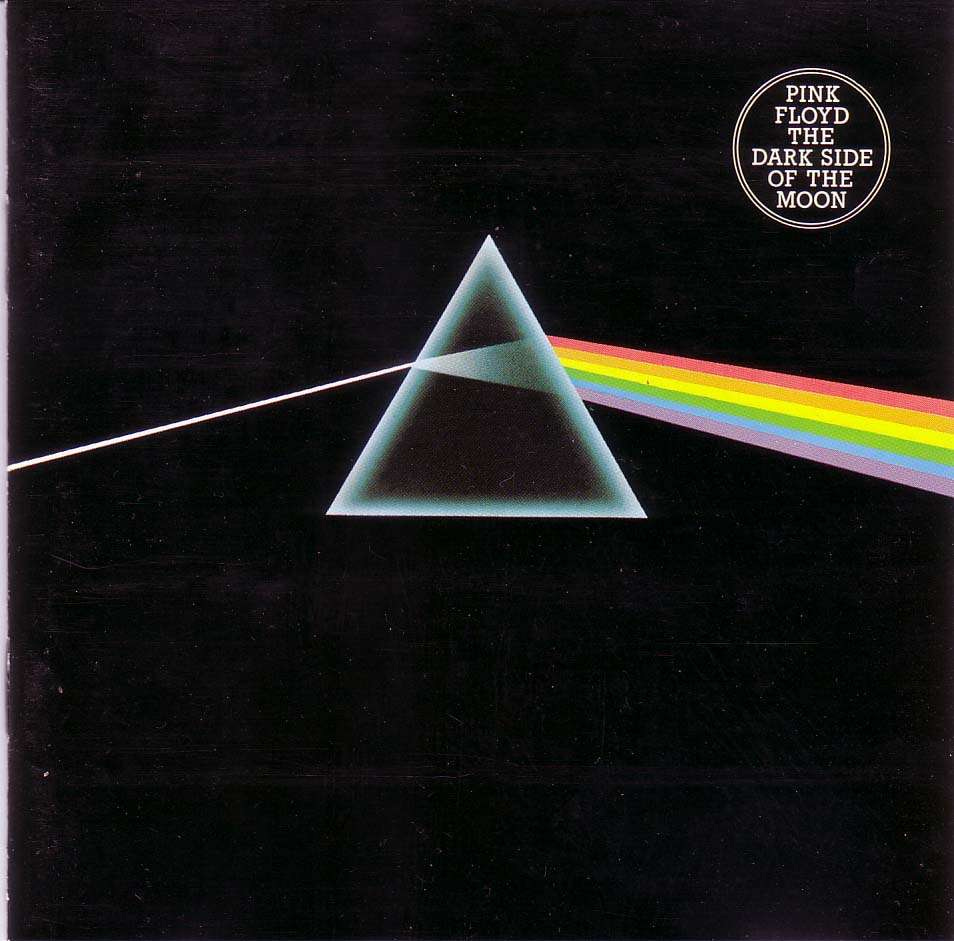

All dressed up, we arrived as the party got underway around the small lit pool, with servants setting up the feed under a grass-roofed cabana. The subdued light and the cool evening created a wonderful tropical ambiance as only Phnom Penh could provide. Music I’d never heard before, Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon, was wafting over the stereo system.

And the moment I first heard this track embedded that night forever in my memory.

Track three on The Dark Side of the Moon, On the Run is a jittery, propulsive instrumental that simulates a breathless airport chase - complete with synth pulses, whooshing blades, and disembodied voices. Heard poolside in Phnom Penh, the track sounded like choppers flying right overhead on a combat assault. Looking back, it played like a warning: the calm before the curry.

Released in March 1973 not long after the Paris Cease-Fire Agreement for Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, The Dark Side of the Moon was Pink Floyd’s eighth studio album - and their most iconic. Conceived as a concept album, it explores themes of time, madness, mortality, and modern anxiety, all stitched together with tape loops, analog synths, and philosophical fragments. Tracks like Time, Money and Us and Them became became anthems of existential unease.

The album’s seamless flow and sonic experimentation - especially on instrumentals like On the Run - created a listening experience that felt less like a collection of songs and more like a psychological journey. It became a global phenomenon, spending over 14 years on the Billboard charts and selling more than 50 million copies worldwide.

By the time it drifted across that Phnom Penh poolside, it wasn’t just music - The Dark Side of the Moon was mood, prophecy, and warning.

Food was served: a delicious curry with rice and all the condiments, and a couple of other dishes. Kim-Dung and I were sharing the time together, not talking much and watching the other guests, mostly fellow journalists. Pink Floyd continued, and soon Kim-Dung started swaying to the music, raising her hands in the air and was looking so absolutely radiant that all eyes turned towards her. I was feeling pretty good myself, and watched in fascination.

Then, in a flash, Kim-Dung became suddenly serious. She looked into my eyes and blurted out, ‘Are we stoned?’

‘Yes, apparently so,’ I replied. ‘Somebody must have slipped something into the curry.’

I tried getting her to continue relaxing and enjoy the mood. But no. ‘Get me out of here – I want to go back to the hotel,’ she pleaded, her eyes wide. As a Vietnamese in Cambodia, she was scared. When we got up to leave, I realised that I was even more stoned than Kim-Dung, who’d only had a half-spoon from the spiked dish.

Le Phnom Hotel was just a couple of blocks away, and damn it if I didn’t get lost on the way there. The rest of the night passed very slowly, and Kim-Dung was not terribly happy the next day. It was her one and only ever stone.

They hadn’t wanted me at that party, and now I understood why.

Back in Saigon from my busiest and most productive assignment ever in Cambodia, my first job was to cover South Vietnam’s provincial and council elections, which now was hardly an exercise in democracy so much as President Thieu’s phoney Democracy Party consolidating its power. Kim-Dung’s father was running for election again down in Go Cong; after he’d stirred the pot over the province chief’s corruption over the past four years, the Saigon government made damned sure he and his colleagues wouldn’t succeed.

While hardly surprising, the results brought home how hopeless and depressing South Vietnam’s political scene had become. And with nothing happening with that Council for National Reconciliation and Concord, my Third Force friends were more miserable than ever.

Nothing like an unexpected dose of edibles