Now in early 1971, as a couple posts ago about the disastrous Laos Invasion, I was finally off that damned photo desk in AP’s Saigon Bureau editing film all day and out in the field shooting pictures and writing stories. With my fluent French, Cambodia and Laos became regular assignments - and very laid back moments too - until the final collapse of the old French Indochina in 1975. As readers might recall, I almost slipped into Phnom Penh in March 1970, expelled at the airport, as Prince Sihanouk’s government was going down in a military coup and could’ve well been there with my good friend Sean Flynn and Dana Stone when they disappeared on their motorbikes in eastern Cambodia the next month. (Would I have gone too, or talked ‘em out of it, I’ve wondered ever since?) Another lucky star moment of my life.

I’d adored a Cambodia at peace in late 1968 and now, just after the Laos Invasion began in February 1971, I returned to a now war-torn country - thanks a lot Nixon & Kissinger! - on my first assignment. A second - and much more poignant one - followed just after my witnessing the total disaster of that invasion up north had become.

And so back to further excerpts from The Bite of the Lotus: an intimate memoir of the Vietnam War (2020) and those memorable days.

And now, almost a year after I tried and failed to slip into Cambodia as Sihanouk was overthrown, I finally got an assignment to Phnom Penh. But Kim-Dung objected. Our friend Sean Flynn’s disappearance and those dreadful post-coup massacres of Vietnamese only confirmed her prejudice against Cambodians, an especially deep-seated sentiment in the Mekong Delta, which, of course, had once belonged to them too. ‘What do you want to go there for?’ she asked angrily. ‘They’ll kill you too!’

Despite the war raging around the country, I found Phnom Penh still quite pleasant. AP had a suite at the city’s grandest hotel, formerly Le Royal and now Le Phnom, with a quite relaxed work pace: a morning briefing and another in the afternoon with copy dropped by the PTT, or post office, for cabling out. Thankfully, not much was happening. A Peter Ustinov lookalike Englishman named Robin Mannock was AP’s stringer there, and a great storyteller. The ambience was still very French. Marijuana was plentiful, and much stronger than anything back in Vietnam.

Robin’s help-yourself stash of dope sat in a wicker basket right on the office desk, and we’d end the day with our first joint and a local pastis, milky white on the ice, from the Cardamon Ranges of western Cambodia. Then a fine French dinner at the hotel or restaurant in town, and on to Chantal’s wooden stilt home off Monivong Boulevard at the other end of town for a few relaxing pipes of opium.

In her early thirties, the large-busted and French-speaking Chantal was a protégé of the legendary Madame Chum, to whose opium den Sean had introduced me after Angkor Wat in 1968. Chantal carried on the civilised tradition of slipping into sarongs before stretching out on colourful mats in a small wooden room. An in-house masseuse was on-hand to accentuate one’s relaxation.

Having spent so many years already in South Vietnam, I genuinely loved the Vietnamese, and had even adopted many of their prejudices. But after a few days I grew much more sympathetic towards the Cambodians, a deep affection that many longer-stay journalists also absorbed, and recognised how badly done they were by the Vietnamese. Not only both sides in the war, but historically, as they’d expanded ever southwards from the Red River Delta around today’s Hanoi.

Whether US policymakers were conscious of it or not, we were contributing to Vietnam’s own ‘manifest destiny’. ‘Torn between the Thais and the Viets,’ I wrote my folks, ‘they’ll be lucky to come out of the war with much of a country left at all.’ This reverse prejudice continued to haunt me on successive returns to Cambodia.

I also came back to Vietnam with a succinct counter to the widely used line – especially by the Communists, but also by anti-government demonstrators – that Americans were imperialists, or đế quốc mỹ. ‘You think we’re imperialists,’ I’d say to any Vietnamese who’d listen. ‘But what about you? After kicking the Chinese out after 1000 years in 938, you pushed south, wiping out the Cham, took over Saigon and then the Mekong Delta from the Cambodians only 200 years ago. You would’ve taken all of Cambodia if the French hadn’t come in the 1860s.’

‘How do you know that?’ they’d reply. ‘You must be CIA.’

‘Nope, I just know your country’s history.’

* * *

[I came back to cover the disastrous ending of the Laos Invasion and returned.]

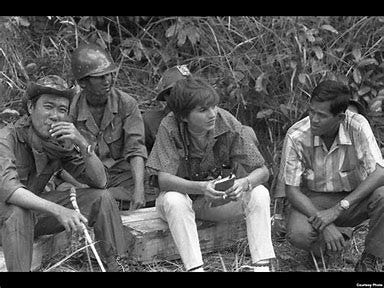

I’d met New Zealand-born Kate Webb at the UPI office not long after she’s arrived in Saigon in 1964. Later with rival AP, we met a couple times in Cambodia where she clearly made a name for herself, especially after her capture by North Vietnamese troops in early 1971.

Soon I was back in Cambodia. Fighting had flared along Route 4, south-west of Phnom Penh, and in an ambush by North Vietnamese troops several journalists were captured, including UPI’s New Zealand–born Kate Webb, whom I’d first met back in Saigon in my USAID days. Fortunately, she was released about a month later – but not before she’d been reported dead.

Our stringer Robin Mannock was wounded, and I was rushed over to help, this time on the news side. I was also given the mysterious assignment of accompanying Dana Stone’s wife, Louise – who’d stayed in the Tu Do Street apartment for a while after his and Sean’s disappearance but was now living in Phnom Penh – up to the provincial capital of Kompong Cham, 100 kilometres to the north-east, on the Mekong River. AP had intelligence reports that two foreigners were spotted on the river’s eastern bank.

Louise was the wife of photographer and later cameraman Dana Stone who disappeared with Sean Flynn, son of actor Errol Flynn, in eastern Cambodia in April 1970. They adored each other and he always called her Smizer, her maiden name. She died of sadness in 2000.

The trip was surreal. I didn’t know Louise very well, but she was deeply depressed about Dana’s disappearance the year before. She was certainly aware that Sean and I were good friends; perhaps she blamed him for their going missing. Petite and thin-lipped, with long brown hair, sad eyes and soft voice, Louise hardly said a word during our four-hour drive in a dark-blue Mercedes limousine that had once belonged to Cambodia’s queen mother. Thankfully, nothing happened along the mostly deserted road.

In Kompong Cham we were greeted by the military governor himself. After lunch, his aides drove us in jeeps up the west bank to the very end of government lines, where we interviewed a few villagers, who had no information.

We spent the night in a large high-ceilinged bedroom in the governor’s mansion, with Louise in a bed on one side of the room and me on the other. Mosquitoes buzzed annoyingly in my ears through a mostly sleepless night, as I imagined Louise gently crying for her lost love. What a terrible pain to bear.

The next morning we crossed over to the eastern bank of the Mekong River, where the Cambodian government’s control barely extended beyond the ferry landing. Again, no one had heard of any captured foreigners. Dejectedly, we headed back to Phnom Penh.

Many years later the information would prove correct: Sean and Dana were not far to the south-east, where they were later executed by the Khmer Rouge.

Back in Phnom Penh, I got into the routine of filing a couple of round-up stories a day on the war. The morning military briefing was literally held under a banyan tree in the garden outside an old two-storey French villa, not far from Le Phnom. We journalists waited at a small tin-roofed cafe for an information officer to tack up a typewritten communique on the massive tree trunk, on the overnight military activities. Yet getting accurate and timely information was always difficult.

When the war first broke out the previous year, the Lon Nol government trotted out a quiet-spoken Cambodian Army colonel named Am Rong as its spokesman. But everything was collapsing so quickly that he was nicknamed ‘Am Wrong’; his reputation never recovered.

His offsider was a young Animal Husbandry graduate from Louisiana State University named Chhang Song, now a captain who spoke with a southern accent. Sometimes Captain Chhang hung around and answered a few questions, but mostly the journalists conferred on what to do for the rest of the day: stay in town or head out on the road to cover the fighting. Many had their own favourite fighting colonels and brigadiers out in the field, who would flesh out the information released at the briefings.

The press corps in Phnom Penh was a tight-knit and relaxed group. Especially after the horrible loss of so many colleagues in the first couple of months of the war, everyone knew and cared about each other. Most were freelancers from around the world – Asia, Europe and the US – and held a very strong affection and loyalty for the Cambodians. Kate Webb’s capture, therefore, along with some Cambodian journalists, came as a real shock.

No one wanted to go out into the fighting, but that was how many, especially the cameramen and photographers, made a living. A quietly spoken Australian, Neil Davis, whose material for Viznews went mostly to NBC, was a mentor for every new arrival, showing them how to cover combat.

Another part of the daily routine was debriefing photographers from the field for the evening news roundup. We also needed to get their film over to Saigon by what we called a ‘pigeon’, a time-consuming process that often involved driving out to the airport, finding a friendly-looking passenger on an outgoing flight who was willing to carry a large and mysterious envelope to the AP office once they arrived. The system worked remarkably well. At least we were spared the task of processing, editing and transmitting photos in Phnom Penh.

Our stories and messages went out by old-fashioned cable, which was a short drive away at the PTT, and always with an extra copy for the censor. But after a certain time of night, usually around 8 pm, the cable office closed, so any spectacular attacks on the city or its airport had to wait till dawn. International phone calls were impossible.

Despite the war all around the capital, Phnom Penh’s languid charm persisted. Driving the office’s tiny Datsun sedan, I became more familiar with the town, especially its river frontages and legendary Four Arms, where the Mekong River from the north widens into a vast pool and splits into three branches. With Sihanouk in exile and Cambodia now a republic, the nearby royal palace was closed off and almost deserted, although its legendary apsara dancers still went through their paces inside.

No matter what had happened during the day, the evenings always ended with a visit to Chantal’s comfortable opium den, and those slow and easy, but oh so intellectual, conversations with my fellow journalists, even the odd French and Malaysian diplomat. After a long and dreamy night, my favourite early morning hangout was Le Café de la Poste, across the small cobblestoned square from the PTT, to have some fresh orange juice, filtered coffee and a freshly baked croissant or two.