Cease-Fire Blues: As Vietnam Faded from the Headlines in 1973, the World Moved on.

GRUMPY OLD VIETNAM HAND.

My last excerpt from The Bite of the Lotus: an intimate memoir of the Vietnam War, captured those frantic early days following the Paris Peace Accords cease-fire of 27 January 1973 - the moment when many southerners, myself included, clung to fading hopes of genuine peace and a political resolution.

America salvaged its image, securing the return of its POWs and the withdrawal of its last uniformed troops from South Vietnam. Yet its chosen proxy, South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu - whose reluctant agreement had been forced by relentless U.S. pressure - remained firmly in power.

A surreal calm settled over the South, but little truly changed. For the outside world, and especially for the media, the Vietnam War was already yesterday’s story. Focus quickly shifted to new flashpoints and, in the U.S., to President Richard Nixon’s escalating troubles over Watergate.

The only thing I was truly looking forward to in early May 1973 was three months of round-the-world ‘home leave,’ including another visit to AP headquarters in New York - and where this chapter’s excerpt picks up.

Flying first-class – a rare privilege at AP – Kim-Dung, Laura, Alexander and I headed off on our round-the-world trip, with a brief stopover in Hong Kong. To avoid the usual hassles of US Immigration and Customs in Honolulu, we flew to Vancouver on a luxurious Canadian Pacific DC-8. After a short flight to Seattle, we continued to Denver to spend time with my parents and Nina, who was completing her last year of high school.

…

The three-month break from Vietnam was just what I needed. Spending the first few weeks, including Easter, in Denver, we travelled up into the Rocky Mountains, where my folks had just built a cabin. We bought the adjoining lot. And I did no unauthorised interviews with the Denver Post this time around (see earlier excerpt from 1969.)

Then down to Fort Collins to see John Black, now a US Army major, our old MACV advisor friend from Go Cong who had come with us to Long Hai all those years ago. We then hit the road, catching up with my old friends Carl Adams and Bill Robbins in Berkeley.

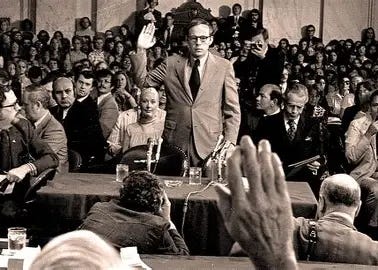

The US Senate’s Watergate hearings, which would ultimately bring down President Nixon, were just starting, so we spent days in Berkeley watching the proceedings live on TV and then a constant accompaniment to our entire time back in the U.S.

And on to the Midwest, where we caught up with brother Jim and his family in Champaign-Urbana, and sister Elizabeth, now called Libby, up at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

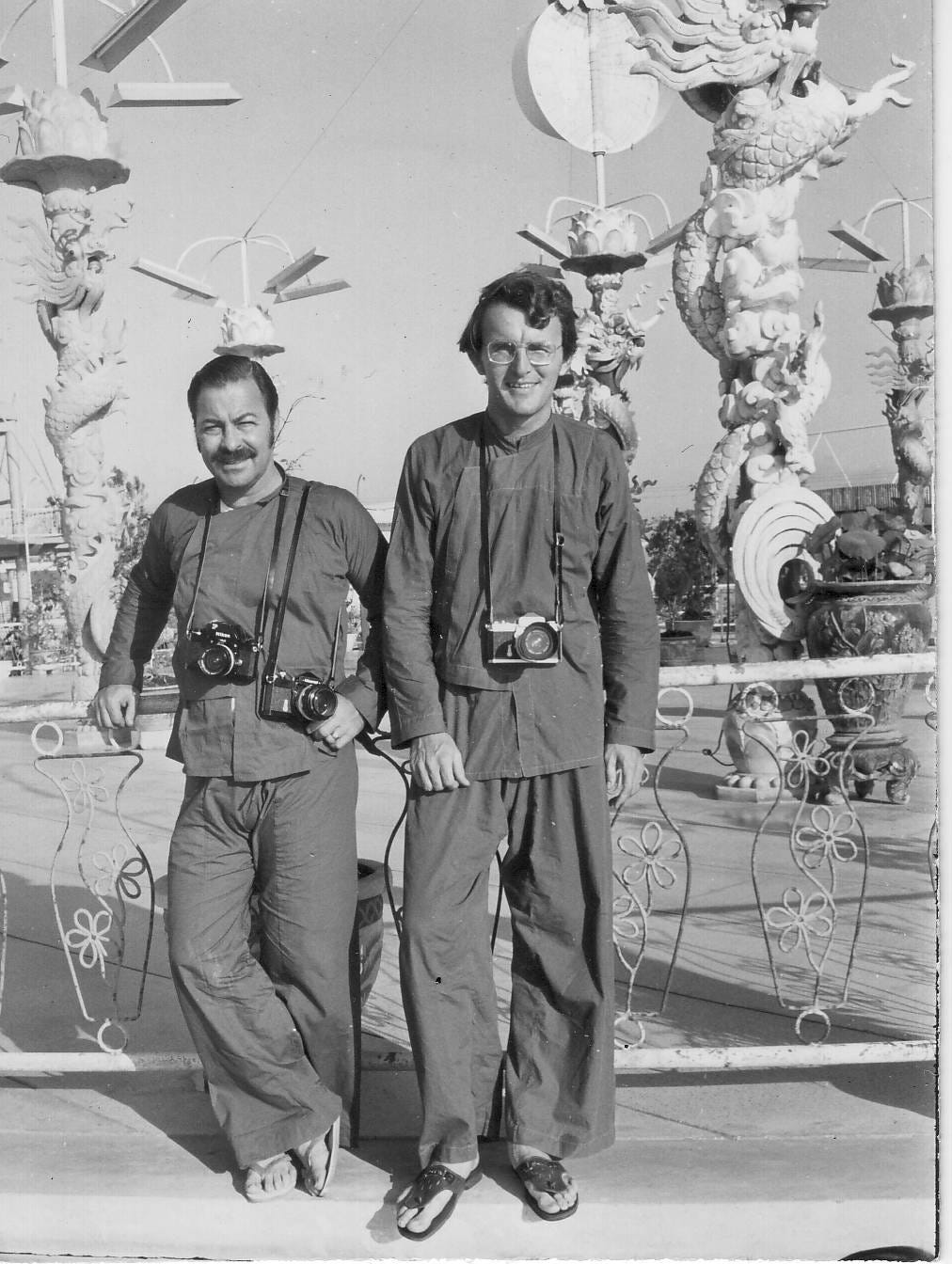

From AP’s Miami Bureau, Jim Bourdier (L) - seen here visiting the Coconut Monk’s Island in the Mekong Delta - took over as Saigon Photo Editor when Horst Faas moved to Singapore in late 1969. A stark contrast in personality, Jim was generous in supporting my transition from the desk to the writing side. I later replaced him when he returned to Miami in late 1971, while Horst Faas returned for emergencies like the ‘72 Easter Offensive and the ‘73 Cease-fire.

Flying down to Miami, we spent a few days with my predecessor as AP Saigon photo chief, Jim Bourdier, and his wife, then went up to Satellite Beach to catch up with Uncle Cloud, my mother’s favourite younger brother, and Aunt Lorraine at nearby Cape Canaveral. We enjoyed his daiquiris so much that we stuck around for a couple of extra days.

After my previous disastrous visit in 1969, I wasn’t looking forward to visiting AP in New York. Against my better judgement, but accepting Jim Bourdier’s advice, I played the game of continuing as a photo editor although my passion was writing. With writers a dime a dozen and photo editors always in short supply, everyone was very pleased; AP President Wes Gallagher even took me out to lunch at the city’s renowned Toots Shor restaurant.

But after five years being employed by AP’s Saigon bureau, I was now hired out of New York, with a promised retroactive raise. ‘There will be a job waiting for you when you come back,’ assured photo boss Hal Buell. ‘We’ll blend you into the domestic network.’ For now, though, I’d continue in Saigon.

Everywhere around New York City, TV sets ran live coverage of the Senate Watergate hearings, including the explosive testimony from nerdy-looking presidential aide John Dean, implicating Nixon himself in the burgeoning scandal. Where was this all going?

Over the weekend, Richard Pyle and his wife, Toby, popped up from Washington for a pleasant Sunday brunch at a lovely Central Park eatery with other former Saigon staffers, including AP’s first woman correspondent there, Edie Lederer. Afterwards, we strolled around the park, checking out the hippies.

I also found time to catch up with other Vietnam friends, including the writer Michael Herr, whom I first met at the Tu Do Street house, and CBS correspondent Jack Laurence.

Looking forward to some first-class travel back to Saigon the other way around, I was disappointed when Pan Am, already running late, laid on a brand-new 747 with a capacity of 450 economy passengers on the lower deck, and not enough room in the small upstairs lounge for us. We were downgraded and arrived in London tired and miserable.

After a few days, we shifted over to Paris, with plans to travel on to Germany to visit Kim-Dung’s cousin. But with the weak US dollar, crowded summertime Europe and just plain weary of the suitcase life and dragging the kids around, we hopped on an Air France 747 back to Saigon with a visa stopover in Bangkok. Happy for the first few days, I soon began spiralling back into the same old slump.

* * *

Not much had happened in South Vietnam while we were away. President Nguyen Van Thieu had visited Washington in early April, and was assured by Nixon of continuing military and economic aid. But the heavily Democratic Party–controlled House of Representatives and Senate now dictated the war policy. And their first step, right after Thieu’s visit, was to ban any reconstruction aid to North Vietnam without US Congressional approval – an odd decision, it seemed to me, given how it could’ve been a very useful lever in smoothing post-war relations.

In early June, all parties to the Paris Agreement re-signed a 14-point ceasefire agreement, and my first job back was an AP news analysis on its failures. But one notable success for the North was the US clearing those mines out of its harbours; soon enough Soviet and Chinese ships were back in port, and not just bringing marshmallows.

Thank goodness the long-serving and overly patrician US ambassador, Ellsworth Bunker, whom I’d loathed for years, was gone. But his replacement, the mousy Graham Martin, would prove an even greater disaster.

Also in June 1973, a US Senate committee began probing that ‘secret bombing’ of Cambodia before the March 1970 coup, never mind that Prince Sihanouk had given his approval, which he now publicly denied.

Most critically, Congress blocked funds for any further US military action in South-East Asia, and most visibly brought an end to the bombing in Cambodia on 15 August 1973. Known as the Case–Church Amendment, the law also effectively negated Nixon and Kissinger’s promise of a strong military response to North Vietnam’s resuming the war.

What with all the gear the Americans left behind, including helicopters and aircraft, South Vietnam’s million-man military looked impressive, on paper anyway. But it was hardly a cheap operation to run, much less maintain properly.

And in the leadup to the ceasefire, Thieu had seriously overextended his forces, grabbing long-held Viet Cong strongholds like the Plain of Reeds, Chuong Tien and Camau’s U Minh Forest, all in the Delta region.

Plus, South Vietnam could hardly continue the same wasteful tactics the Americans had used throughout the war, like H&I (Harassment & Interdiction) artillery fire and saturation bombing, and even close-in artillery and air support. Soon the NVA were using the Soviet-made heat-seeking rocket known as the Strela, or Sam-7, to blow VNAF choppers and aircraft out of the sky. Frightened South Vietnamese pilots now dropped their bombs from even higher up in the sky.

One boozy evening in the months before the ceasefire and his departure as AP Saigon’s Bureau Chief, Richard Pyle and I were analysing things when I came up with my ‘Rotting Barn Theory’ about South Vietnam’s chances of survival.

Just like one of those big red barns spread across America’s sprawling Midwest, everything would look good for a while, I argued. And then one day, a wall would fall over, and then another, before the entire edifice collapsed in a heap. We laughed sourly at the idea, though I never meant to be quite that prophetic.

Towards the bottom of the Paris Agreement, both sides had inserted an article ‘Regarding Cambodia and Laos’, which intended to bring an end to the Vietnam War’s spread into those neighbouring countries.

The North Vietnamese were clearly in violation, with their continued use of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Up in Laos, which already had experience of coalition governments, both sides were progressing towards one more. Shortly after my return, therefore, I was back in Vientiane for a week to cover the negotiations.

But in Cambodia, on the eve of the bombing halt ordered by Congress, the situation was much worse, with the Khmer Rouge insurgents tightening the noose around Phnom Penh, which was now totally dependent on river convoys up the Mekong River from South Vietnam, and even then was under constant attack.

And now stories emerged that the US, after everything they’d done to Cambodia, was begging for Sihanouk to return and lead a coalition government, a proposal the prince flatly rejected from his Peking exile.

After one last burst of bombing, including the accidental B-52 bombing of the government-held Mekong River ferry town of Neak Luong, killing nearly 150 civilians, the Americans finally and ignominiously wrapped up their dozen years of combat activity in Indochina on 15 August 1973.

In one of his rare forays out of the office, Bureau Chief George Esper, accompanied by our only Western photographer, Neal Ulevich, headed over for the historic moment, the last laconic words coming from a US pilot, who waved his wings and then headed back to his base in Thailand.

With Esper away for a couple of weeks, Tad Bartimus, who had replaced Edie Lederer as AP’s second female correspondent, and I ran the office. More used to soft stories, Tad was struggling a bit with the daily war roundups – well, the ceasefire roundups. One day she asked me: ‘Is 300 mortar rounds on an outpost a lot?’

‘Yes – just imagine yourself sitting under that,’ I replied.

We clashed repeatedly, but when an exiled Royal Laotian Air Force general staged a farcical coup in Vientiane to disrupt the coalition talks, we were charging away, with her taking dictation over the phone from our stringer David Jenkins, and me writing the stories, one urgent wire story after another all day. Brigadier General Thao Ma crashed his lumbering propeller-driven T-28 at the capital’s airport and was later executed. The talks continued.

Henry Kissinger, now inexplicably treated as a rock star despite the wobbly situation in Indochina, became Nixon’s new secretary of state, and a couple of months later he and Le Duc Tho were bizarrely named joint winners of the year’s Nobel Prize for Peace, an award the latter wisely refused to accept. I covered South Vietnam’s upper-house elections, which were overwhelmingly rigged in Thieu’s favour, with an amazing turnout of 99.2 per cent.

* * *

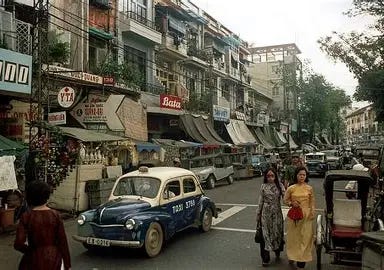

Everything was fine at home. We’d brought an ice-cream machine back from the US, and our first batch was Durian Ice Cream. Yum! And in something of a first for Saigon, we’d also brought a waterbed – with all the passionate wave-making love that would produce. Laura was back in kindergarten and learning English, which we practised at night. Alexander was a real clown, lots of fun and still forming his words. Despite needing constant repairs, the Citroen served us well for trips down to Go Cong or the beach. At least the roads were safe now.

In early September, I turned 30. Mindful of the cliché of the day – ‘Don’t trust anyone over 30’ – I spent the day ignoring the milestone, saving my energies for Laura’s fourth birthday the next day, when all her little friends would be coming over.

George Esper headed off on home leave, with Tad and me running the office. ‘I wouldn’t be surprised to see New York reduce this bureau to a roving correspondent who pops his head in once a month,’ I told my folks.

Saigon’s sidewalk kiosks were full of great books left behind by departing Americans, and so, for the first time in years, I went on an extended reading kick. South Vietnam was experiencing a kind of peace after all, but we never knew when the shoe would drop.

For an R&R we headed down to Singapore, where I lounged by the luxurious Goodwood Park’s swimming pool while Kim-Dung shopped, and then it was up to Bangkok for a few more days. Staying at the comfortable Montien Hotel at the top of Bangkok’s Patpong Road, Kim-Dung collected a dozen colourful tropical birds for our planned rooftop aviary back in Saigon and, for good measure, an adorable German shepherd puppy. Thai Airways insisted that all the Saigon-bound animals needed papers, but Kim-Dung talked them around; the South Vietnamese customs people barely took a second look. Shep would become our best dog ever.

Yup, that’s how we dressed back then! Using my Leica M-5 to cover the arrival of Pathet Lao troops in Vientiane as part of the Paris Peace Accords on Laos, a new coalition government, here some of them atop of Soviet-built truck. I was rubbing shoulders with Russian and Chinese photographers and cameramen on this assignment.

Up in Vientiane, the Soviets arranged the arrival of Communist-led Pathet Lao soldiers and police from their zone up in north-east Laos. Meanwhile, all hell broke loose in Bangkok with a student-led uprising against the military dictatorship, with heavy anti-US overtones. I souped and radiophotoed my pictures from Laos, then rushed back to Saigon to be with Laura, who was heading into hospital with a tonsil infection. The Bangkok uprising climaxed with a demonstration of 500,000 students, and the shooting deaths of over 100 of them.

Meanwhile, South-East Asia slipped off the front pages completely as the Yom Kippur War broke out in the Middle East and an oil embargo was imposed by Arab nations against the West, touching off fuel shortages and dramatic price rises, leading to worldwide inflation. US vice president Spiro Agnew resigned over corruption allegations in Maryland. And the Nixon administration continued its agonising unravelling amid growing calls for the president’s impeachment over the Watergate scandal. By mid-November 1973 Nixon was whining ‘I am not a crook’ to the annual Associated Press Managing Editors’ conference.

‘Another outpost overrun by the North Vietnamese, a shakeup of generals and ministers, charges and counter-charges about the ceasefire,’ I reported to my folks. ‘Vietnam is still on the teletype but now just another story, along with Northern Ireland, the Cold War, more executions in Chile, more kidnappings in Argentina and, of course, the stock and metal markets and endless scores of football games.’