Or more accusatory: “You’ve gotta’ be CIA!” Who me, are you kidding? And for my entire adult life too, even in Australia. Those early years as a US Government civilian in South Vietnam triggers ‘em all the time. And let’s face it, folks, South Vietnam was one big 30-year CIA Op -- and I was there for 11 years. (Something wrong there, right?) But anyone saying or thinking that flatter themselves. Of course, I wasn’t a spook, dammit. Do you think they’d hire a CO (Conscientious Objector)? Or a missionary’s kid? (My fellow Congo schoolmate John Stockwell might care to explain himself on that one.) No, I’m too smart. And it is kinda’ funny when a particular insight about global politics and history triggers and wonders.

During the Vietnam War, the Communist propaganda constantly hammered us as Đế quốc Mỹ (American Imperialists) and that sing-song expression became a running joke between myself and Vietnamese staffers in Saigon’s Associated Press (AP) Bureau, especially a couple photographers. And then as my knowledge of Vietnam’s 4000-year old history grew, I recognised it wasn’t just us. Just like all those NVA (North Vietnamese Army) fellas coming down the Ho Chi Minh Trail today, the Vietnamese had pushed southwards from their Red River Heartland for the past thousand years, wiping out the Cham Empire, taking over the Central Highlands, grabbing Saigon from the Cambodians and taking over most of the Mekong Delta, a process ending barely 200 years ago.

“You think we’re imperialists,” I’d forcefully tell any Vietnamese who’d listen. “What about you? You are Đế quốc Việt.” Silence. And then they’d say, “How do you know that? You’ve got to be CIA!”

No, hardly. I’ve just read up on you. But the Vietnamese love a good intrigue and certainly saw the hand of the CIA everywhere. Most simply, everything in South Vietnam was so screwed up that it just had to be one huge CIA chaos operation.

By war’s end in 1975, as you’ll read later in my excerpts, I was quite sympathetic with the Third Force under the enigmatic ex-General Duong van ‘Big’ Minh and like them desperately hoping for a coalition and neutralist end to the war. I was close to an opposition deputy in South Vietnam’s National Assembly and journalist, Ly Qui Chung, and we’d often meet for coffee as police agents watched nearby. Just normal and increasingly pessimistic conversations. But with the NVA now at the gates of Saigon on 28th of April, Big Minh became President and my friend Chung the new Minister of Information. The next day, the helicopter evacuation was on and faced with getting out some of my wife’s family, or none at all, I took what I call the Confucian Option and missed out on the Fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. For the next 20 years, my friend Chung believed I was CIA and ordered out by them, even writing so in his own memoir. Thank goodness, our friendship resumed after 1995.

Famous Viet Cong agent and Time magazine employee Pham Xuan An (in white shirt) and I became good friends after the Vietnam War when I’d often catch up with him at his Saigon home, here pictured with former colleagues Richard Pyle of AP (R) and Daniel Southerland (UPI & Christian Science Monitor), his wife and myself during a visit in April 2005. An passed away a year later in 2006, aged 79. Three books and many articles have been written about the old spy.

And the infamous “Spy who Loved Us,” Pham Xuan An, who turned out to be a Communist agent working for Time magazine. Something about him I never trusted, warned about from one of those Vietnamese colleagues mentioned above, and always kept my distance. I didn’t like his narrative creating influence with Vietnamese staffers working in the western media. I had my own sources. We finally met up at a journalist reunion in Saigon in 2000 atop the Caravelle Hotel, where a couple TV networks stayed during the war.

We shook hands and I sat down and spoke quite directly, “You know, I never trusted you, An. I was warned about you.” And what was his reply? “Well, I never trusted you either. I thought you were CIA.” Laughs. We became good friends until his death in 2006.

Of course, growing up well-read on world events, I knew of CIA operations like the Shah of Iran, Guatemala and the Cuban Invasion before arriving in South Vietnam as a university student in early 1964 from Hong Kong and later hired up with a one-year contract with USOM (United States Operations Mission) Rural Affairs, as a young ‘pacification’ advisor down in the Mekong Delta. And, yes, I’ve only recently learned, USOM was indeed set up by the CIA in the early post-1954 days of South Vietnam and later handed over to USAID, the Agency for International Development, by the time I returned for my second tour in 1966, now hired out of Washington. (See my earlier Substack posts on my early days in South Vietnam.)

The CIA was a remarkably overt - as opposed to covert (secret) - operation in South Vietnam and they were literally everywhere and in everything, plus instantly recognisable by their green Ford Broncos (then a brand-new model), the font of all their vehicles’ licence plates and its clean-cut guys with those oh-so-cool folding stock Swedish-K 9mm Submachine Guns. They even had their own airline for gosh sakes and which they later contracted out to USAID.

The Helio-Courier was one of several short take-off & landing (STOL) aircraft operated by Air America, the CIA-run airline in South Vietnam, and here taking off from just outside Go Cong with the CIA officer I’d just boldly met.

I was still young (only 20) and learning spook protocol when an Air America Helio Courier landed one dusty dry season day on a road right outside Go Cong town in early ‘65. My curiosity brought me into the MACV (Military Advisory Command-Vietnam) Team’s villa where I met the civilian aboard who’d dropped by for a coffee. Nice plane you got there, I remarked and then blurted out, “Are you with the CIA?” Silence. Gulp! “I’m with the Embassy,” he quietly replied. And that was their Code Word. Never mention CIA. Or perhaps entre-nous, “The Agency.” The real US Embassy guys would clearly identify themselves from Political, Economic section or whatever. These guys were a totally separate operation with own offices & hotels.

And as I’ve related here earlier, I was quite close to a veteran spook in Go Cong Stew Mayse (a real name?) where we simply agreed to call it XYZ - and kept drinking our gimlets (vodka & lime juice) and smoking Filipino cigars and reminiscing about his days running the Cuban Operation out of Miami.

So, they were everywhere. In the Pacification Program, they trained what they called RD (Revolutionary Development) Cadre in black pyjamas, just like the Viet Cong, to live and work in newly-reclaimed hamlets, supposedly anyway. (Most hot-tailed it back to town where they’d been hired, not country folks.) They ran Provincial Interrogation Centres (PICs) to track down the VCI (Viet Cong Infrastructure, or underground) and then send their US-led Counter-Terror (CT) Teams out to get ‘em in what later became the Phoenix Program. What else? Infiltration from the North working with special forces.

Domestic South Vietnamese politics? I’m sure they were doing something, but not with me, probably just buying off or even creating opposition parties to make the Freedom & Democracy Franchise look legit against the US-backed military dictatorship. Oh, well. We know how all that worked out in the end.

And then two years after the Fall of Saigon in 1975, the AP assigned me to Sydney, Australia, where I soon sensed quite a bit of anti-Americanism, especially in leftie politics and the media, over the famous dismissal of Labor Party Prime Minister Gough Whitlam. (He’d angered US President Nixon by openly criticising the Christmas Bombing of Hanoi in 1972 just after his election and relations went downhill from there.) In what’s called a “regime change” operation today, many believed the US was behind the sacking of Whitlam in November 1975 - and in a big leap after all those years in South Vietnam, just why was I in the backwater of Australia, eh?

And then after AP sacked me in May 1978, I decided to stay and got a job on a Sunday newspaper until its new editor - who was a huge proponent of America’s supposed intervention in ‘75 - clearly snubbed me and forced my resignation. But he’d definitely screwed around with my reputation and over coming years, I was often point-blank if I was a spook. Well, who’s spreading that, I’d wonder out loud?

Now working for Newsweek magazine in the early 1980’s, I was with Labor Party Opposition Leader Bill Hayden one day at Canberra’s Parliament House and just finished my interview. He paused and watched me closely as I switched off my tape recorder and then asked, “Are you with the CIA?” Gosh! Him too. My whole life. And, of course, even today back in today’s Vietnam.

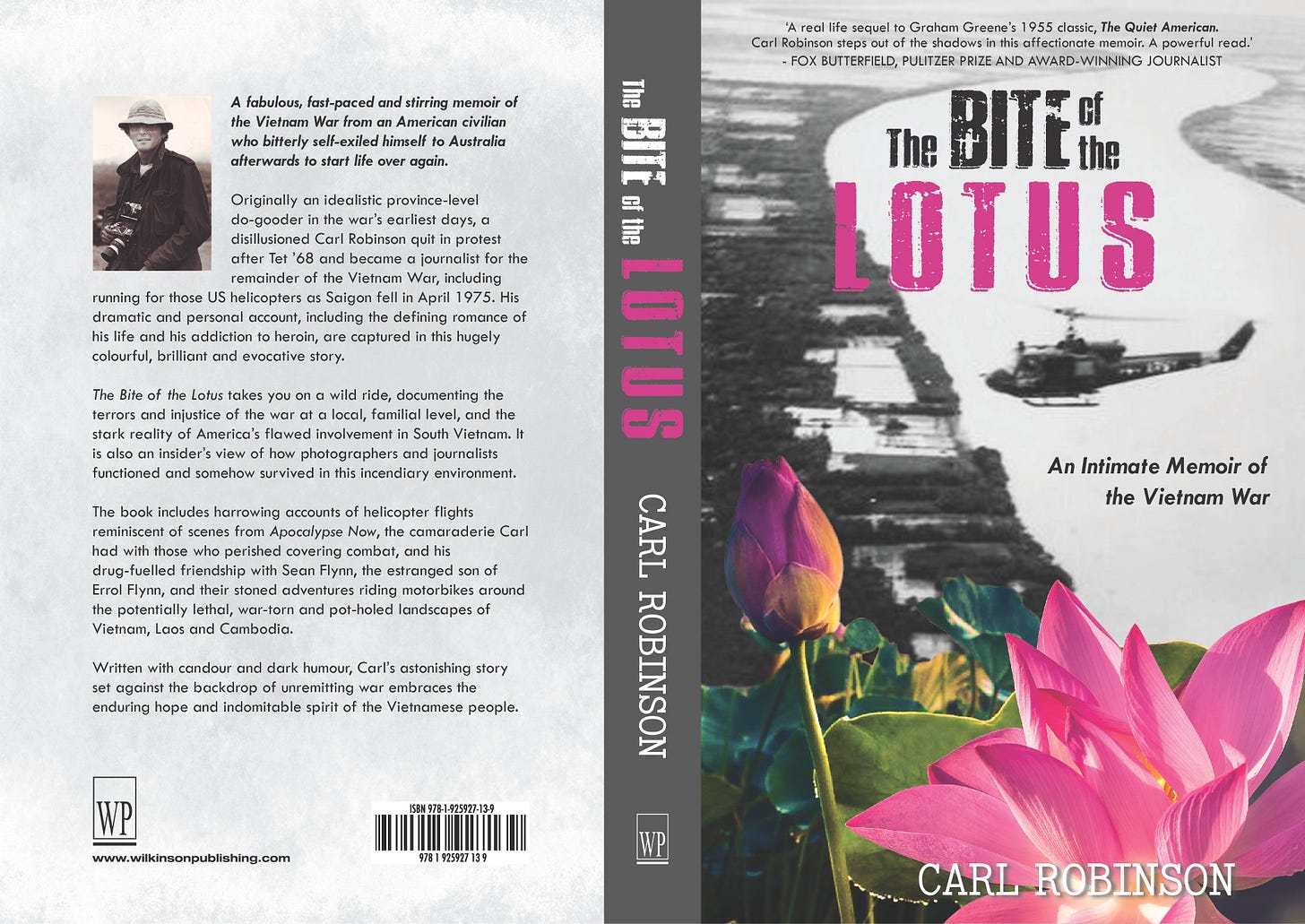

And so now, just to prove my bona fides here, folks, I’ll end with another excerpt from The Bite of the Lotus: an intimate memoir of the Vietnam War and one of my favourite stories from Vietnam too. I would never ever lie in this situation now, would I?

And now, with Tet coming up – this one in mid-February 1969 – it was time for some serious marriage talks with Kim-Dung’s family. Important tasks must be completed before the Lunar New Year, which is why so many weddings happen before Tet. In our case, we just needed a decision.

We were both nervous about travelling down to Go Cong on my motorbike in late January. This time I had no Vietnamese-speaking colleague around to help me. And Kim-Dung was in the odd position of playing matchmaker – or interpreter – at her own marriage negotiations.

Sitting together at a small table, her father and I ate a simple but delicious lunch of crispy fried chicken wings on a bed of watercress and sliced tomatoes with vinaigrette dressing and steamed rice, which Kim-Dung and mother had prepared. A memorable favourite. Then the serious negotiations began.

Her father had three questions. Was I married already? It was not a dumb question, as many Americans were taking second wives in Vietnam – with all the ceremony, even the paperwork – and later abandoning them.

‘No,’ I replied. ‘I have never been married.’

Kim-Dung was the oldest of five children from the second marriage of both parents, whose earlier ones had produced three older girls. And so, with no number-one son or daughter in southern Vietnamese culture, only twos, she was number five, or Nam, which was how she was generally addressed, except by her own parents, who called her Dung. This daughter was not just beautiful but precious too, and her father worried that I’d be taking her away, never to be seen again.

“Are you planning to leave Vietnam,” he asked.

‘No,’ I honestly assured him. ‘I am not planning to leave Vietnam. I never want her to lose touch with her own family.’

He seemed satisfied, and then said: ‘I have one more question for you. If I am satisfied with your reply, you can marry my daughter.’

‘Yes?’ I replied anxiously. ‘What is it?’

Taking a deep breath, and then looking me straight in the eye, he asked, ‘Do you work for the CIA?’

I laughed out loud and looked at Kim-Dung. That’s his last question? So I’ve passed! ‘No, I’m not with the damned CIA,’ I sputtered, and burst into a wide grin. ‘So I can marry your daughter now, right?’ We all laughed.

Preparations for our wedding began. But first we needed to fix a date, and not just any date. Kim-Dung’s mother consulted a soothsayer – I don’t like the term ‘fortune-teller’ – to pinpoint an auspicious day. After just one look at our animal years, however, he threw his hands up in despair. ‘No, these two are not compatible. She is a Buffalo and he is a Goat.’

Of the 12 animals on the lunar zodiac, we were directly opposite each other, and that wasn’t good, apparently. Plus, our respective horns would, logically, always be locking together and fighting.

‘But they’re in love and we’ve given our approval,’ protested Mother.

Reluctantly, the soothsayer continued his deliberations, and finally declared that there was only one auspicious day in all of 1969, the 26th of May. Otherwise it would have to be next year. Okay, then.

Please get in touch if you’d like to receive a signed copy of my memoir. Thank you!