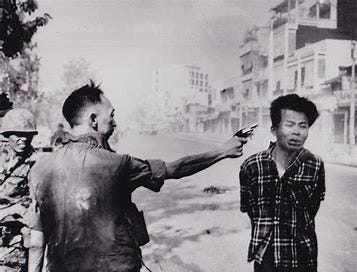

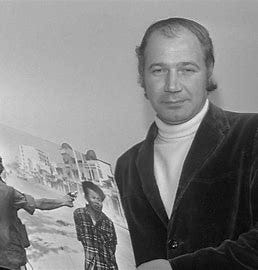

I joined The Associated Press (AP) in Saigon after the Tet Offensive of 1968 after angrily quitting USAID. Photo boss Horst Faas hired me out of a Saigon bar. Photographer Eddie Adams was there too, fresh from his shot of the street execution of a Viet Cong by South Vietnam’s police chief just weeks before. I was a total new guy writing captions and learning photo editing, a job to stay in-country with my new Go Cong sweetheart Kim-Dung. Eddie was an ex-US Marine with lots of combat photo experience, like most of our photographers and stringers, a totally different world from my civilian pacification job down in the Mekong Delta.

While I would certainly build close friendships with many combat photographers over the coming years until the Fall of Saigon seven years later in 1975, Eddie and me just didn’t hit it off. Ten years older. Living in another world. Irascible. Quick-tempered. Made his own assignments. Didn’t like me editing his film. But mostly, I soon reckoned, because he regarded me as “Horst’s Boy” and the two despised each other. The German-born Pulitzer Prize Winner Horst Faas and very all-American Eddie Adams. Photographers have bigger egos that chefs, I tell ‘ya!

Looking for a job to stay in South Vietnam with my young sweetheart after quitting USAID in protest over the conduct of the war, AP’s photo editor Horst Faas hired me as a caption writer and photo editor out of a hotel bar. He & Eddie did not get along and I was collateral damage in forming any sort of friendship as I did with other combat photographers.

After the Fall of Saigon in April 1975, I ended up on the World Desk at AP Headquarters in New York City and Eddie Adams around too, working on news feature stories and I’d run into him in the AP cafeteria on the overnight shift. Black hat. In fact, dressed all in black. Never said much. A certain mockery on his face. Maybe we should’ve finally talked about the war. But none of us wanted to back then. Just shove it silently behind us and forge on with our lives, helped by dope & booze.

For me - and literally married to the place - my own looking back at my Vietnam square in the eye didn’t happen for another 20 years and after my return there in 1995. Eddie Adams also took his own time confronting his own personal demons over that infamous photo. Much has been written elsewhere how the photo came to dominate his life and his struggles with that. He passed away in 2004.

Based on true events, here is Robin Hemley’s fictionalised account of the first meeting between Eddie and the General at his Virginia mall restaurant back in 1990 and which I’d like to share with you below. Robin is a good friend and writer who introduced me to Substack. His story was published , the story was written in a year and a half ago and published earlier this year in Conjunctions.

You can follow Robin at https://substack.com/@robinhemley.

Les Trois Continents Robin Hemley (Burke, Virginia, 1990)

“I came here to apologize,” Eddie tells the man.

“What is there to apologize for?”

“The photo. It’s ruined—” He doesn’t finish. He’s unable to speak.

When Eddie Adams calls Les Trois Continents, a woman answers in Vietnamese-accented English. “Les Trois Continents,” she says. “We’re not yet open. Call back at eleven.” And hangs up. He calls back, a mere thirty seconds closer to eleven, and she answers in a weary voice, but before she can repeat what she’d just said, he interrupts. “I’m calling for your husband,” he says, “not about food.”

“My husband is dead,” she says. “What do you want?”

Eddie wonders if this is fate—he’s finally screwed up his courage to call Nguyen Ngoc Loan, and the guy drops dead? Car accident? Cancer? Most likely suicide. But no, he’s made a false assumption, hasn’t he? It’s his nerves.

“I’m calling for Nguyen Ngoc Loan.” “He’s not my husband,” the woman says. “My husband is dead. You think all Vietnamese people are related?”

He apologizes and tells her he doesn’t think anything of the sort. “Could you just tell him that Eddie Adams would like to speak with him?” The question is met with several thuds. The woman must have answered on a wall-mounted phone. He imagines the phone dangling, repeatedly hitting the wall.

“What do you want?” General Loan (presumably) asks in a tone as businesslike as the woman but not as gruff by half. A simple question but not easy to answer.

When you photograph someone, when it turns out to be a notable photograph, your life and theirs are connected forever. Taking a life is similar. When one dies, both die, he’s sure of it.

When people ask Eddie about that photo he took on the chaotic streets of Cho Lon in 1968, he tells them that two people were killed that day, the man with the bullet in his head and the man who pulled the trigger.

“I’d like to stop by,” Eddie says. “I’d like to talk. Do you know who I am?”

“I know who you are,” the man says. “You can come when we open at eleven, before the noon rush. We’re located in Rolling Valley Mall.”

The general’s English is impeccable, better than Eddie’s. Eddie grabs a pad from the nightstand and the nubby pencil that rests on top, knocking over several empties in the process. He never drinks in the morning but this morning gives the lie to that. He writes down Rolling Valley on the notepad. Though he already knows the address, the action of writing down something is a comfort. The man hangs up. Lying in his bed, Eddie writes Rolling Valley over and over until the piece of paper is full, like some old-fashioned grade-school punishment. The words conjure up nothing—not even the rolling valleys he has known, from the Western Pennsylvania valleys of his youth to the valleys of Southeast Asia. He’s known a lot of rolling valleys deeper than any you’d find around a strip mall in Burke, Virginia.

Several hours later, he parks his rental near the entrance to the restaurant. The mall, as he expected, is sad and empty. He could park across three spaces if he wanted. The only businesses that seem to be thriving are a Blockbuster Video and a nail salon. Les Trois Continents has a big front window—there’s virtually no one inside. Eddie expected at least a little elegance with a name like Les Trois Continents. Instead, an unlit neon sign announces pizza in the window, and he would assume the place was closed, maybe even out of business, but for the presence of a couple of guys in suits seated by the window, drinking coffee and spearing pizza slices into their mouths. Maybe he’s arrived at the tail end of their lunch service, not that he wants any, and they’re closed until dinner. He has arrived later than he said he would, stupidly falling asleep after his phone call. It’s 12:45 now. Still, only three booths are occupied.

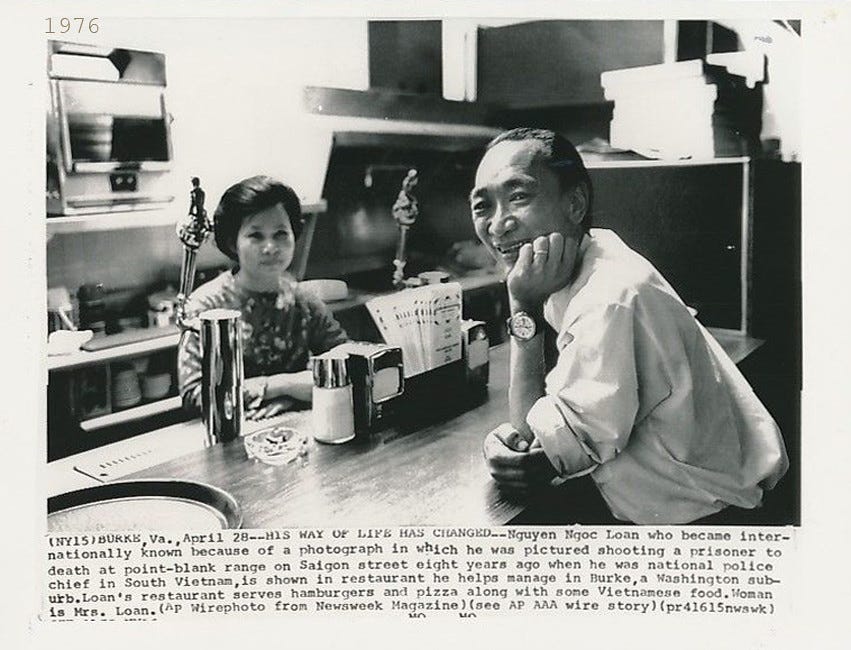

This AP story in 1976 - just a year after the Fall of Saigon - hardly hardly helped the former South Vietnamese police general who’d settled into a modest eatery in Burke, Virginia, called Les Trois Continents. Like all early post-war Vietnamese refugees, he was granted ‘parolee’ status as an immigrant. But public knowledge of his presence touched off calls for his expulsion and investigation by immigration authorities a “war criminal.” The case was dropped, thanks in part to a petition from Eddie Adams. But they didn’t meet until another dozen years later.

The only hint that the place has a connection to Vietnam is the pictures on the wall—tourist posters from the sixties, it looks like. Two women on the back of a motorbike on Nguyen Hue Street, the opera house, the obligatory rice paddy, nothing from the North, of course. And it’s not likely the restaurant will be getting replacement posters anytime soon. His own photograph, not an enticement for tourists, will never grace these walls, of course, though in another sense, it’s there, undeniably. He bets he’s not the only person here who sees it. Invisibly visible. He could live the rest of his life without seeing it again. But sometimes we don’t get to choose what we’re known for, if anything. His new wife, like his old wife, thinks he should just be grateful.

The woman whose husband is dead—he’s pretty sure it’s her— seats him next to an unplugged jukebox, across from two booths occupied by white customers. She places a menu in front of him as a Vietnamese American busboy who looks about eighteen fills his glass with water. Maybe they’re related, maybe not. He’s not conducting a census anyway. He knows that General Loan has three daughters and a son. Two of the daughters seem accounted for—both standing idly by the kitchen. At least, he assumes. He can’t help himself. Assumptions are human. They’re what get us in trouble with other people. And they’re sometimes proven correct. They, not good intentions, are what the road to hell is paved with. The woman returns after only a few minutes have passed and asks if he’s ready to order. He hasn’t had a chance to look over the menu, but at a glance, he sees why it’s called Les Trois Continents. Pizza, burgers, and Vietnamese food. He supposes that counts as three continents.

“How’s the pho?”

“The best,” she says. “You were in Vietnam. I can tell.”

“How can you tell?” “You know pho. Americans don’t know pho. They don’t even know how to pronounce pho. They ask, ‘What’s foe?’ ‘You foe,’ I tell them,” and she laughs. “You say it correct.”

“I called earlier,” he says. “I wanted to speak to Mr. Loan.”

She regards him critically. “You’re late,” she says. “We’re busy now.”

Is she joking? He looks up at her but she hurries off. He thinks he may have ordered but he’s not sure. He didn’t even get to specify what kind of pho he wanted. As he’s waiting, a man in the booth immediately across from him laughs so loudly, it’s more like a shout. The guy looks to be in his forties like Eddie; the woman accompanying him is in her twenties or early thirties. The man speaks rapidly, as though he’s a stand-up comic. Other than that, the room is as quiet as a restaurant can be and still be open. The unlit jukebox and neon pizza sign make him feel he’s landed in some restaurant version of purgatory. Hard times.

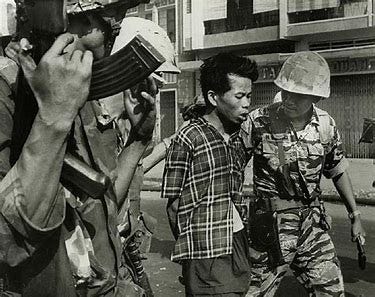

General Loan slides into the seat across from Eddie. A thin man, on the frail side, mostly bald now. The last time they met, if you could call it a meeting, twenty-two years earlier, was on the chaotic streets of Chinatown, Cho Lon, in Saigon during the Tet Offensive. House-to-house street fights, choppers searching for VC, blowing up buildings, streets choked with smoke and the dead. Eddie caught sight of the general and hurried to him—the man in conversation with a subordinate while a handcuffed prisoner waited a few steps away, facing in his direction. Eddie, his peripheral vision honed by the war, was focused on the prisoner’s face, at the same time keeping his eye on the general in his huddle. It was the prisoner who captivated him—while hell was going on all around, he looked like someone waiting his turn in line at a shop.

The general nodded, stepped toward the prisoner with revolver raised, and shot the man through the temple at the same time that Eddie lifted his camera and took the photo. It was a reflex photo. He wasn’t even sure what he had until he developed it at the AP office.

Afterward, the general approached Eddie, revolver lowered, and said calmly, “These people kill a lot of our people.” Some claim that the photograph was staged, that the man never would have been shot if the press hadn’t been there (a camera crew filmed the execution too), but Eddie’s shot was as thoughtless and sudden as the execution seemed.

“Why are you here?” the general asks Eddie.

The question is not put in an unfriendly tone. The woman appears, smiles at the general, sets down a bowl of beef pho in front of Eddie. The scent is sweet but it does not awaken Eddie’s hunger. He’s not sure he can stomach anything. “For the pho?” the general asks, smiling. He urges Eddie with a gesture to eat, but Eddie just takes a sip of his water. “I was talking to someone at the Times about my obituary,” Eddie tells the general.

“Oh,” the general says. “Are you dying?” Eddie feels like he’s dying, but it’s a false death. A momentary death, fuelled by drinking when he doesn’t even drink anymore. Death of willpower. Death of best intentions.

“No,” Eddie says. “I plan to live another hundred years. I’m going to wait awhile. Death is the biggest kick, you know. That’s why they save it for last.”

This makes the general chuckle and Eddie leans back. He’s been sitting on the edge of the seat until now. “A guy from The New York Times called me up the other day and asked if he could interview me for my obituary. They do it all the time, apparently. I gave him what he wanted but before he hung up, I asked him what the lede would be. Before he could answer, I recited it, ‘Eddie Adams, war journalist and photographer, who won the Pulitzer Prize for his photo of the summary execution of a Viet Cong prisoner during the Tet Offensive, died on Friday in Manhattan at the age of 192.’ Something like that, the guy told me, but not as clunky. And the age of death seemed a little overly optimistic.

But that was the point, I told him. No matter how long I lived, no matter what else I do in my life, no matter how many greater photos I take, this will be what I’m remembered for. And you too.”

He points to the general, who nods. “As soon as I hung up, I told my wife I had to leave—we have a newborn and—”

The general interrupts. “Congratulations,” he says.

“I’m not the kind of guy who just abandons his wife on a whim to drive to Virginia, but that’s the kind of guy I am, I guess. My wife told me she understood why I needed to make this trip.” He’s not sure why he’s telling the general this—it’s not the general he needs to convince.

“I came here to apologize,” Eddie tells the man.

“What is there to apologize for?”

“The photo. It’s ruined—” He doesn’t finish. He’s unable to speak.

Eddie finally takes a spoonful of his pho as cover, pretending to savour the sweet broth. He breaks his chopsticks in two and rubs them together as though he wants to start a fire. One of his Southeast Asian skills: his expertise with chopsticks. This won’t be mentioned in his obituary but to him it’s noteworthy. He grabs a thin slice of beef. “The thing is, I’ve followed your story. The deportation hearing back in the seventies. The renewed negative publicity lately. I read that business has been slacking, and that you’re closing the place? Is that true?”

The general nods. “The rent is too high here. Are you going to eat?” The general watches him expectantly until finally Eddie tastes the beef. Ordinarily, he would devour the rest of the bowl. He doesn’t tell the chief that if there were an obituary flavor of pho, this is what it would taste like. He’s not even sure what he means by this. He could say it tastes like death, but that’s an exaggeration. It tastes like one specific animal’s death. Will this finally convince him to go vegetarian, as he’s intended for so long?

“God, this is good,” he says and the general smiles. It’s not a lie. He knows it’s good while at the same time it’s like a fist plunging to the depths of his stomach.

“The man you shot—”

“Nguyen Van Lem,” the general says without pausing, blinking, or looking away.

“No one ever talks about what he did—why you shot him. I believe that if they knew, they would think differently about you. I wanted to say I’m sorry. I drove here from New York to tell you this.”

The general, whose eyes have not left Eddie’s, folds his hands on the table. “If you hadn’t taken the photo, someone else would have. I believe I will be forgiven.” He emphasizes that word “believe.”

So the general has religion—Christian, Buddhist, who knows? For Eddie, forgiveness is more local than cosmic. Still, he imagines that in the scale of things, the general’s crime is less than Nguyen Van Lem’s. A child murderer. Not just one child but six. Can any just cause justify that? The general’s crime is known only because Eddie and a camera crew were there to record it. What if they had been inside the house to record Lem’s crime? He’s often pondered this. Would people feel any different about the general if Eddie had been there to take photos as Lem and his group blew away Lt. Colonel Nguyen Tuan, his wife, six of their seven children, and his eightyyear-old mother? Or maybe a photo of the one surviving child, a nine-year-old boy, shot three times, lying still in his mother’s arms, listening to her fading heartbeat as she bled to death? The boy, he heard, was adopted by an uncle, and made it to the US. Eddie hopes he’s doing well, but he can’t imagine what horrors must fill his dreams. Or maybe he has been able to move past this trauma, has focused only on his future. What does he feel when he sees Eddie’s photograph? He’s sure he’s seen it. Everyone has seen it.

“I was filled with rage,” the general says, his eyes unwavering. If it were Eddie recounting this, he would look at his hands, his lap, the wall of outdated touristic posters. “But not for the reason you might think. If he had been in uniform, I would not have shot him. He was a coward. He could kill this family and then fade into a crowd because he didn’t have the courage to wear a uniform and say, Yes, this is who I am and this is what I have done.”

“I get it,” Eddie says. “That’s why I’m here.” And he does get it. He was a marine before he was a photographer. Some things you must own up to, no matter the consequences. He just wishes he could be known for another photograph, one that’s more positive. At least half a dozen others deserved the Pulitzer more than his accidental shot.

“Excuse me. I have to visit the washroom.” The general smiles and points to the end of the room, past the older man and younger woman, past several empty booths, to the bathrooms, one with the wooden figure of a man in a conical hat on the door, the other a woman in an ao dai.

Inside, he feels like he’s going to vomit, but wills himself not to. He’s a loud retcher. Everyone in the restaurant would be able to hear him. At the urinal, he puts his forehead against the wall in front of him. He hates beer. Hates regret. He ruined the man’s life, but the general won’t see it that way. He’s made a pointless trip. It’s time to return to his child and his wife—he has plenty else in his life to be proud of.

But his will is no match for the practical reflexes of his body. As he stumbles to the toilet, he wonders what it sounds like out in the restaurant. Like the explosive shout of a gorilla meant to carry across valleys and mountains. It is one of the worst sounds a human can make. He grabs some toilet paper from the dispenser, wipes his brow, and notices some graffiti above the toilet: “We know who you are, fucker.”

When he finally emerges from the bathroom, the other customers are gone, their tables bused as though no one ever sat there. Only the general and the woman remain. The rest of the general’s family, if that’s who they are, have fled elsewhere, maybe huddled in the kitchen, waiting for the crazy man to leave without doing them harm. The general sits exactly where Eddie left him, looking out at the parking lot as though it’s a mountain lake. Eddie goes to the cash register and quietly asks for his check. What would Eddie even say now to explain himself? The man hardly seems to notice that Eddie is leaving, and it seems that the woman doesn’t notice him either, though he’s standing right in front of her. She’s counting money from the register, unmoved by his presence. He must still be a little drunk. It’s not only his appearance that’s dissheveled but his thoughts as well. What if he’s already a ghost? What if he just died in that bathroom and doesn’t yet know it? What if three people died when he took his photograph in the mayhem of Cho Lon? The woman stops counting, sets a small stack of five-dollar bills aside, and glares at him as if still upset that he didn’t show up at a more convenient time.

(With author’s permission. Uncorrected Proof@2020. Conjunctions.)

In May 1968, the Communist-led Viet Cong staged a second offensive on Saigon - called Mini-Tet - and General Nguyen Ngoc Loan was shot and severely wounded in the leg in the city’s Dakao District along the Thi Nghe Canal. Here, just hit, Australian journalist Pat Burgess - later a good friend in Sydney - helps pull him to safety. A divine justice.