As the ceasefire in South Vietnam crumbled in mid-1974, so did everything else—work, health, hope. This penultimate chapter of The Bite of the Lotus, titled Dysfunctionality, spirals through dark moods, bad habits, meeting up again with a black U.S. Army deserter fresh from prison, and fleeting glimpses of salvation in a hospital revival meeting. A descent and a reckoning. And then my wife, Kim-Dung, said she wanted to stay and settle down.

Cambodia and Laos had been a great break from the increasingly annoying routines of the Saigon’s AP office. Hardly a day went by when Bureau Chief George Esper wasn’t blowing his temper at someone, either one of our Vietnamese staff or good old Neal Ulevich, who, with me away so much, was running the photo desk. Thankfully, I was spared Esper’s outbursts, but, as I wrote in my diary, ‘they might as well be directed at me for the disturbing effects on me’.

The ceasefire was staggering along, with the most intensive fighting yet up in the Central Highlands, where the NVA (North Vietnamese Army) still had a couple of divisions. In the Mekong Delta, Communist forces recaptured areas lost in Saigon’s pre-ceasefire land grabs. President Nguyen Van Thieu warned of a new offensive but no one believed him. He’d cried wolf too many times. The Democrat-controlled House of Representatives refused to increase US military aid to the Saigon regime. I couldn’t disagree; Saigon had plenty of hardware. What we needed was peace.

The rainy season arrived, and with it came a new test for Saigon as the NVA overran the isolated ARVN base of Ton Le Chan, between the VC’s traditional base areas of War Zones C and D, some 60 kilometres north of the capital. Thieu used the battle as an excuse to cancel talks in Paris on a political solution – the moribund three-part Council of National Reconciliation and Concord seeking a coalition government – and suspended the weekly Camp Davis press conferences, even cutting the phones. But nothing changed.

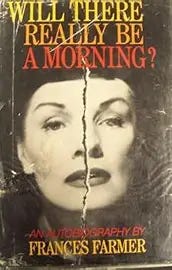

The situation in South Vietnam was more depressing than ever, and I dropped into a black hole. Influenced by the posthumous memoir of the 1930s American actress Frances Farmer, Will There Really Be a Morning?, which I garnered from Robin Mannock’s bookshelf up in Vientiane, I started wondering about my own mental state. Plus I was back on the smack again.

Frances Farmer’s Memoir Will There Really Be a Morning? (1972) A posthumous, searing account of the 1930s actress’s fall from Hollywood grace into the brutal machinery of psychiatric institutions. Farmer’s voice - lucid, bitter, and poetic - chronicles her collision with mental illness, forced confinement, and the long crawl back toward lucidity. A haunting meditation on identity, control and the cost of defiance. It isn’t just a memoir - it’s a warning flung through time, fragile and furious.

Prefacing his remarks with the hope that they wouldn’t piss me off, John Giannini remarked that I was too talented and had too much experience to keep playing the AP game, and suggested we take off to Africa and start a news-photo agency there. I could never leave Kim-Dung and the kids behind in this place, but John had made a telling point about me and the job. ‘I feel a need to get out of this routine, this hole, this lifestyle,’ I wrote in my diary. ‘What is the AP ready to offer except more of the same frustrations? Rewards for mediocrity . . .’ The only hope on the horizon was a rumoured AP plan to locate a new roving correspondent in Bangkok.

I desperately needed to get off the smack. This stuff was running my life. ‘How strong a person am I?’ I wrote one night. ‘Strong enough to finish things off and feel “sick” for the rest of the day – until a gut ache starts to hit, eyes water and a general uneasiness settles in. A time to look into myself and think how tempting a night ride would be to that depressing corner of the sprawling blob of a city only inches above the permanent water level to buy another stash. A head problem . . .’

Everything looked and felt dirty and grimy. I wondered if I wasn’t crazy but sick. in my diary, I wrote, ‘And it’s one of those days where you hope it rains and it does and then turns into a low grey day where everything’s wet and sad and you hardly sweat except for that damp wetness under the arms – and cigarettes taste bad and your muscles ache and your head is on a low boil.’

After the final US troop withdrawal in March 1973 following the Paris Cease-Fire Agreement, Saigon’s vast 3rd Field Hospital outside Tan Son Nhut Airbase became a civilian hospital treating remaining Americans in South Vietnam and also South Vietnamese. I personally experienced both iterations of them over my 11 years as a civilian in Vietnam.

After the US Army closed its 3rd Field Hospital out near Tan Son Nhut and all the troops left after the ceasefire, the facility was taken over by the Seventh Day Adventist church, which already had another hospital for Vietnamese nearby. The sprawling facility continued treating Americans and other foreigners, and now locals too.

A missionary doctor named Dr Sinclair had put me on a methadone program the year before, with neither very positive nor long-lasting results. Thankfully, he wasn’t judgemental, but after holding his stethoscope up against my chest said I had a wheeze and should get a chest X-ray.

Well, packs a day of those unfiltered Bastos wouldn’t help anyone’s health, and I had felt a bit short of breath lately. He also recommended a blood test to see if my liver was functioning right – perhaps a recurrence of hepatitis.

As I waited for a couple of hours, I was reading another Lew Archer whodunit by Ross McDonald, another paperback from Robin, when I began chatting with a tall black dude who said he was Jamaican and married to a Chinese. We watched as a tall toothbrush-moustached US Army lieutenant colonel, clearly on DAO (Defense Attache Office which’d replaced MACV) business, led around a troupe of a middle-aged Vietnamese woman and three children.

‘Do you know two or three wives a month return from the US – in boxes?’ the dude asked.

I hadn’t heard that one.

‘They get knocked off,’ he continued, ‘or knock themselves off. The South Vietnamese embassy in Washington is full of sad girls who want to come home after failed marriages to undereducated white trash, and of course the embassy can’t help them because they’re no longer Vietnamese citizens.’

Back home after my trip to the hospital, my grim mood was hardly helped by the mob scene of a house full of relatives from Go Cong, with no sign of Kim-Dung, who’d popped down to Vung Tau with the kids for a couple days. Leaving a note and skipping the laid-out lunch, I headed into the AP office.

Later, as I headed back out to the hospital to pay the remainder of my morning bill, temptation struck and I pulled into my connection to pick up another stash. The small two-storey reinforced concrete and brick house was part of a grimy neighbourhood of tightly packed homes, many simple tin-roofed shacks, and full of refugees from the war in the countryside.

Heading upstairs, I was wordlessly greeted by a familiar Vietnamese in his twenties. I entered a room with a double bed in one corner and some low but comfortable enough lounge chairs beside a round glass-topped table.

I hadn’t seen Carl Brown for a while. About my height, he was a black US Army deserter, and the only person I’d ever seen who shot up this high-octane heroin. He’d spent five months in Saigon’s Chi Hoa – the same dreadful French-built prison where Kim-Dung’s dad had been a political prisoner back in the late 1950s – and had just beat a murder rap. He was with another dude named Dan, who was talking about heading off to Africa and becoming a mercenary.

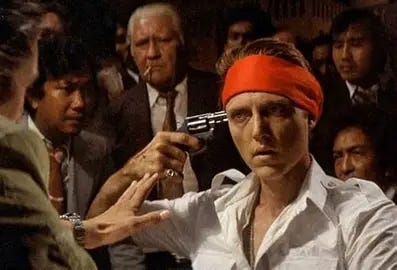

In The Deer Hunter (1978), Christopher Walken’s character - an American lost to heroin and Russian roulette - remains in Saigon as it collapses. Though dramatised, the scene echoes the real, undocumented fate of U.S. deserters who stayed behind after the ceasefire, drifting through the city’s underworld as history closed in. What happened to them?

The Ones Who Stayed: U.S. Deserters in South Vietnam. When the last official U.S. troops left Vietnam in early 1973, they weren’t the only Americans still in-country. A small, shadowed cohort of US military deserters stayed behind - men who had vanished from their units, gone underground in Saigon, and reappeared in black-market dens, safehouses, or alleyway bars.

Some had Vietnamese partners. Some ran hustles. A few, like Carl Brown - fresh out of Chi Hoa prison after beating a murder rap - were still drifting through Saigon’s drug-ridden underbelly in mid-1974, a year and a half after the ceasefire.

By the time Saigon fell in April 1975, few traces remained. There are no clear records of what happened to them. Maybe they fled. Maybe they were captured. Maybe they simply disappeared. I have often wondered what happened to this other Carl and his friend Dan.

They aren’t in the history books. The ghosts of the “peace.”

A return visit to the hospital shortly afterwards revealed that I had worms, and the doctor speculated that the little buggers had got into my bloodstream and were screwing up my lungs. I had shades of the Congo, when we kids were regularly de-wormed by Mom, whether we needed it or not. ‘Eat your dinner or the tape worm will,’ we were always warned as kids. At least this explained my gut-aches, I reasoned.

The doctor also suggested I attend the hospital’s first stop-smoking program, and I soon found myself in the middle of a revival-style congregation of foreigners and Vietnamese, all standing and raising their hands, and shouting, ‘I choose not to smoke!’ Our evangelist leader was virtually rolling his eyes heavenward as he uttered, ‘If you stay with us, we’ll see you through to victory.’

Drinking lots of water and fruit juice to flush the nicotine out of my system, and changing my diet to include more fruits and salads, I stopped smoking and felt better – and hornier. But I was still cheating with a couple of smack hits a day.

My black mood was lifting. I was determined to control my moods. Off sick for a couple of weeks, I enjoyed my time with the family, especially with Alexander while his sister was at school.

Then, to my surprise one evening, Kim-Dung announced that she wanted us to stay in Vietnam for the rest of our lives. Settle down, buy a house and some land down in Go Cong. After all, things were relatively peaceful now, despite all those ceasefire violations out in the boonies. Yes, if it would make her happy, I replied.

Images flashed through my head of that old French geezer who kept the air-conditioning going and put up the movie signs at the Eden Cinema in the arcade below the AP office. That long-lost Pakistani who bitched at everyone trying to get into his pigeon-cage elevator going upstairs.

Or those glum-faced Corsicans who ran restaurants around town, as well as dice games and smuggling rackets. Did I want to be like them? ‘Yes, there’s a great future in this country,’ I mused in my diary, ‘just ask Major Phuong Nam and the boys out at Camp Davis.’

And then I was back at work, determined to keep a positive attitude and catch up on a few feature stories, including one on the Third Force. George Esper was kind and solicitous – overly so, I thought – after a story on a visiting heart team. I was still off the smokes.

And then, during a chat on Sunday afternoon at the end of my first week back, I casually asked if he’d ever known someone who suffered a nervous breakdown. George explained some of the symptoms, and when he asked why I wanted to know, I told him about my own black moods and frame of mind.

The next day, when I came back to work a bit grumpy after lunch, George followed me into the photo department, closed the door and said firmly that he was worried about me; perhaps I should take another week or two off? I readily agreed. I’d barely been able to tolerate that week back at work.

‘Now George thinks that I’m on the verge of a nervous breakdown, although reports from the office seem to indicate more the vice versa,’ I wrote in my diary. George had become so angry one Sunday night over a radiophoto cast to Tokyo that he’d fired Neal again. I asked George exactly what he’d said to Neal, but he replied, ‘I was so angry I don’t remember what I said.’ The main charge apparently concerned Neal’s ‘negative attitude’.