Heroin use in wartime Vietnam had a perverse sort of normality. It wasn’t junkie me sprawled in a back alley - it was casually functional, as routine as lighting a cigarette. A tool to endure, not to escape. But I know the stigma. And there is it, right on the back cover of The Bite of the Lotus: ‘his addiction to heroin.’ Like so much in my memoir, I told the truth, just as I once planned to about the Napalm Girl Photo.

I covered up my addiction pretty well back then - so I thought. But now, as I’ve challenged the Napalm Girl misrepresentation, some are dredging this up to tarnish my reputation. ‘Self-confessed heroin addict’ - another label meant to dismiss rather than engage. But the truth is in my memoir because I never shied away from telling it.

As readers might recall, I made passing references to heroin when I jumped ahead to excerpts from The Bite of the Lotus’s final chapter back in April - marking the 50th anniversary of the Fall of Saigon while I was in today’s Ho Chi Minh City. I also related how I slipped my last stash past navy inspectors aboard the USS Mobile in the South China Sea after my helicopter evacuation from the collapsing South Vietnamese capital.

Today, I openly admit to my heroin addiction back then. People often ask how I gave it up, and my answer is simple: I got on a chopper and left. That’s the only way to handle addiction - get the hell out.

And now back to explaining how that all began as excerpts from The Bite of the Lotus: an intimate memoir of the Vietnam War and that 1973 - 1975 cease-fire period continue.

Note: In early 1974, my younger brother Richard - nicknamed Muk, from his birthplace in the Belgian Congo - arrived in Saigon after six months studying Tibetan Buddhism in an ashram high in the Nepalese Himalayas, in the shadow of Mount Everest. I hadn’t seen him in four years. He accompanied me on a couple of trips before ending up working for USAID in Laos as South Vietnam collapsed, as mentioned in earlier excerpts. Muk later escaped Laos before it also fell in late ‘75.

Back home, Muk was down in Vung Tau for the week, and (daughter) Laura was recovering well from tonsilitis. My brother and I spent a lot of time catching up. I taught him a few photography tricks in case he wanted to stick around, passing him one of my older Leicas. We soon headed off together to Cambodia and then Laos – with me once again on assignment.

With all my trips to Cambodia and Laos, opium was now part of my lifestyle – and my workstyle too, as a few pipes at night, even a good dozen, hardly affected my reporting, writing and photography the next day. I was never all that self-confident, and very much a self-taught journalist and photographer, and opium gave my writing more assurance and coolness.

After that first stiff cup of café filtre, freshly squeezed orange juice and a croissant, I worked flat-out all day – well, with a brief siesta thrown in, and a wake-up coffee – ending with a relaxing joint of marijuana, perhaps an iced Pastis, followed by a convivial dinner.

Then it was off to the opium den with some like-minded folks for a relaxing evening of conversation, and then those pleasant half-awake, half-dreaming hours til dawn. I was a fully functional addict, and living the romantic life of Graham Greene’s Thomas Fowler in The Quiet American.

But a rougher side to my opiate addiction had also entered my life: heroin, that 95 per cent stuff I’d so condemned John Steinbeck IV for taking up. Now I too was hooked. Although manufactured from opium somewhere up in Laos, heroin was very much a ‘Vietnam Thing,’ and a serious problem among US troops in the early 1970s.

With the heroin epidemic affecting 20 per cent of GIs, the US military introduced Operation Golden Flow of compulsory urinalysis for all departing personnel and this is my photo for AP when the program began in mid-1971. By this stage, I was also personally aware of the problem and only an occasional user, such as in that bunker at a US firebase under North Vietnamese artillery fire during the invasion of Laos in an earlier excerpt here on Substack.

Heroin was easily available, and I’d cadged plenty of smokes off others before taking the decisive step of buying my first stash from an itinerant woman cigarette seller at the Tu Do Street entrance of the Eden Arcade, below the AP office. Unlicensed, they’d disappear with their wooden glass-topped cases and folding stands in a flash when police showed up. A transaction took only seconds.

During the GI days, heroin - or smack - was sold in small plastic vials about the size of a large sewing thimble with a screw-top lid; it looked a lot like icing sugar. You poured a few grains into the lid and snorted the heroin. Those with more time unravelled a cigarette about one-third of the way down, shook in a few grains, refilled it with tobacco and twirled the end shut.

You sure didn’t want to shoot this stuff up – it was too strong. Later, heroin was sold in small plastic bags sealed with an iron; they were easy to slip into a wallet or stash of papers, and were less grainy and powdery.

The effect of smoking heroin was almost instantaneous, especially the first hit of the day, as the body responded in a thrilling motion through the shoulders and chest and down the arms, and then a slow, pleasing jerk. The gut relaxed. But compared to opium, where the thrill of that first pipe reached all the way to one’s toes, heroin was less relaxing, more rough and edgy.

And while opium required a certain journey, time and ceremony, and a couple of days later I could be back to normal – whatever that was in this dreadfully endless and depressing conflict – the urge for smack was almost impossible to shake.

By early 1974 I’d been smoking smack for a while, and had functioned fine and got my work done. The stuff was inexpensive, widely available and I wasn’t robbing houses to support my habit of three hits a day.

When we headed off on our regular R&Rs or took extended home leave, I just stopped cold turkey, sometimes cutting the edge with a menstrual pain tablet available over the counter at any Vietnamese pharmacy. I didn’t feel particularly guilty, but did worry about getting found out – either by Kim-Dung or the office.

Almost all my friends had left Vietnam. I didn’t want to make any new ones, worrying about the jinx of having them die, get wounded or disappear on me like so many others had over the years. The handful still around were also into smack; in fact, scoring and smoking was the basis of our friendship.

Never that much of a mixer in the Saigon press corps, I retreated still further into my own company. Booze was out. Sex was rare, as my libido was shot. Music grated my ears and I preferred silence. Heroin seemed to suit my mood, and the mood of Vietnam at the time. I wanted to ignore where the place was going. It was a slow-motion train wreck, and I was a passenger. I’d lived with that gut-ache of dread for years, and could now salve the pain with a hit or two.

Without the buzz of war, Saigon was boring, and AP Bureau Chief George Esper was driving me up the wall at work. That earlier AP office conviviality had morphed into a lack of respect all round, and a depressing dysfunction.

The secretiveness of heroin also suited my personality – an extension of the sneaky stuff from my boarding school for missionary kids back in the Congo. I’d slip into the office toilet or darkroom to prepare another smack cigarette, and then have a sneaky smoke in the open corridor outside. Nobody knew this wasn’t just another Bastos Bleu. The guilt of my secret behaviour also brought pleasure. Even so, I was ever alert, and constantly worrying: were my pupils really that dilated?

In appearance, I was no junkie – at least not then. Always wearing my distinctive rolled-up long-sleeved shirts, but a rather horrendous choice of striped bell-bottom wide-belt trousers from the PX and open leather sandals, I thought I looked pretty damned good. My hair wasn’t terribly long; after all, I might need to visit Singapore. My glasses were stylish gold rims I’d bought in Paris.

Especially with Muk around, I wanted and needed to get off the smack, and I began another diary to convince myself to stop. After all, I couldn’t really write home about this one. I’d tried and failed many times before. My entries were cryptic.

And so, in mid-March of 1974, I escaped to Phnom Penh with Muk, writing of ‘the cold sweat of habits to be left behind and, hopefully, stay away from’. It was folly to blame Saigon’s boredom and George, whom I described as being ‘high without drugs’, but I now had a chance to break away from heroin.

‘How many times have I played this game only to slip back?’ I wondered.

* * *

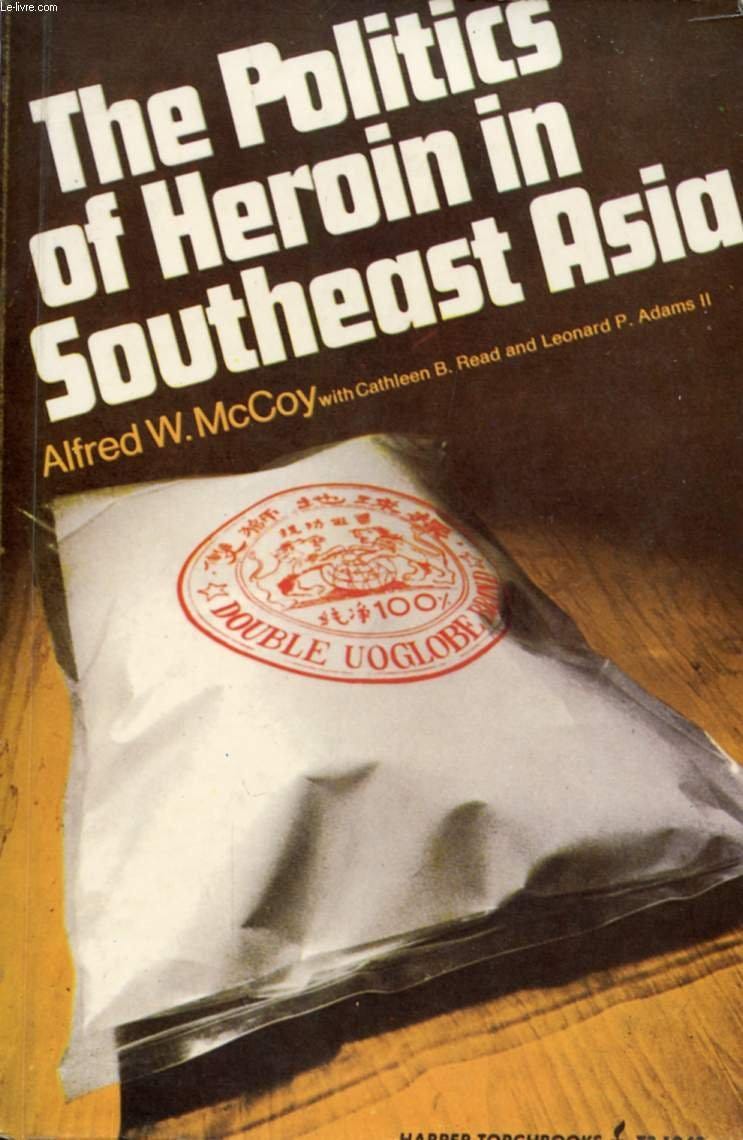

The Politics of Heroin - Alfred W. McCoy’s groundbreaking exposé on the CIA’s complicity in the global drug trade, revealing how heroin became embedded in the machinery of war. I became friends with him after the war in Australia.

While we users didn’t give it much thought, the heroin trade in wartime Vietnam wasn’t a low-level operation - it had backing from figures far beyond the street dealers. Corrupt officials, intelligence operatives, and even elements within the military ensured a steady supply, turning addiction into an embedded part of survival, not just among GIs but many South Vietnamese too, soldiers and civilians alike. Saigon’s generals and senior police officers played a central role, controlling distribution while skimming profits, while CIA-backed operations had their own connections, trading favours for access. It was an open secret - part of the machinery of war, sordid yet functional. And all too conveniently overlooked by history.

Fascinating! Must've been heady days 😅