REDACTED: the true story of the Napalm Girl Photo in my 2020 memoir.

GRUMPY OLD VIETNAM HAND.

“Well, why didn’t you put that in your book, huh?!” You know, like when your The Bite of the Lotus: an intimate memoir of the Vietnam War came out in 2020, eh? And when AP published that ‘painstakingly researched’ 23-page "Hit Piece" - and on a former employee, no less - on myself & the producers of “The Stringer” documentary just before its premiere at the Sundance Film Festival on 25 January 2025, they wrote: “For decades, neither Robinson nor the other photographer publicly challenged Ut’s credit for the photo. There is no reference to the allegations in Robinson’s own book about his time in Vietnam.” Never mind the very same day, Nick Ut’s lawyer was already threatening defamation action and demanding Sundance cancel the show. Oh, well. But good question, folks, so why wasn’t the true story of the Napalm Girl included in my story about my civilian years in South Vietnam from 1964 to its end in 1975?

Well, the simplest is what I wrote in The Weekend Australian Magazine of 8-9 February 2025: “I almost revealed the truth in my 2020 memoir The Bite of the Lotus, but held off, fearing legal action and not wanting to distract from the rest of my years in Vietnam.” I’d also mentioned the legal threat in the 90-minute documentary, specifically referring to what my one-time AP Saigon colleague Peter Arnett - yes, that Peter Arnett - emailed “Vietnam Old Hacks,” the Google Group of former war correspondents I manage, after someone brought up my assertion that Nick Ut did not take the Napalm Girl photo back in November 2015. What a blast! (And do note that I’m not talking out of school here as the Google Group is public & searchable.)

There is not a shred of truth to Carl Robinson's whispering campaign asserting that Nick Ut didn't take the Kim Phuc picture; the Vietnamese staff present in the AP bureau that day, as was I, can and have attested to his authorship. The origins of Carl's bitterness with Nick Ut and other Vietnamese staffers apparently come from the last years of the war when Carl and his family's behavior antagonized many in the bureau. The AP management is well aware of Robinson's patently false private claims made over the past few years and will robustly defend Nick's reputation based on witness statements and AP photographic records of that period, if he decides to go public. Nick himself plans to sue Robinson in a Sydney court on defamation charges should that happen.

I have tangled with Robinson over the years on this matter, and frankly, remain current with the Old Hacks to be in position to ridicule him and call for a boycott of the website if he has the temerity to openly challenge Nick and the AP.

Well, gulp! So, Arnett had told AP management of my assertion after I’d naively reached out to him in 2009 thinking he’d offer some sort of support to the mental turmoil about that photo that I’d experienced since 1972. (And I have his angry email replies too.) And never mind his fib of tangling with me over the years, like when? That last reunion in Saigon in 2015? And throw my wife’s family in for good measure, eh? (What was that accusation and why?) But you definitely get the fella’s Kiwi tabloid training, right?

But it was a lots more than just that suing stuff. I was pushing 70 years old when I reviewed all my previous attempts at autobiography and finally inspired into setting the right structure, mindset and tone. Then, working from an outline of chapters for every period of my life up until the Fall of Saigon in April 1975, I started remembering and writing and, looking back now, was amazingly self-disciplined for a life-long procrastinator.

Something early every morning & every day. Chronological. Born in America, my childhood in the Belgian Congo, back to the US at 15 and - bang! - out of there to Hong Kong and Vietnam five years later which you’ve been reading about here. And I always knew I’d get to this point and writing about exactly what happened with that Napalm Girl photo in AP Saigon Photos on the 8th of June 1972. And when I finally wrote these memories down in mid-2014, I recall a great sense of relief. I’d finally done it!

But my story of the Vietnam War still had three years to go and I was quickly back to writing ever onwards to the Fall of Saigon in April 1975 which opens - and closes my story. It’d taken about 18 months and completed at the end of 2014.

Covering so much time and territory, however, the final manuscript was just too long and too much of a hard sell for my agent Margaret Gee. I couldn’t afford an editor to trim my life story down. Discouraged, I went back to writing about my post-Vietnam days and our settling in Australia, something for the grandkids anyway. Nobody wanted another book about Vietnam, I reckoned.

But then my old Vietnam friend Tom Fox, whom you’ll meet here shortly and also see in “The Stringer,” was visiting Australia in 2017. Wearily, I tossed him the manuscript to read on his travels. He called me back a couple days later suggesting - and inspiring - what turned out to be The Bite of the Lotus.

But dusting off and editing down that monster manuscript to only my years in South Vietnam, I now faced a very serious decision of whether or not to include the true story of the Napalm Girl Photo in the revision. And it wasn’t just that now half-forgotten threat by Arnett after I’d finally written the story down. (And he wasn’t the only one who’d brought up the threat of legal action.)

Something else held me back from including it. What? The opprobrium of former colleagues? Not really, I’d told a few of them privately and most had told me to just forget it. (My friend Tom was the pushiest.) My agent was nervous with books about Vietnam, even journalist memoirs, already a hard enough sell to publishers. Would they also fear litigation?

I agonised for weeks about its inclusion, even seeking the counsel of the rector of the Anglican Church in Sydney’s Upper North Shore where I’d re-discovered my Christian roots. No, and what if Nick Ut took his own life? And call me modest - or perhaps just the powers of rationalisation - but I didn’t want my book to come out and all the attention just on the Napalm Girl photo. My life and experience was much richer than that. No, just another day in the office. Another day in the Vietnam War.

And so in the middle of the second paragraph of page 242 of The Bite of the Lotus: an intimate memoir of the Vietnam War, a couple thousand words went down the redaction chute and replaced quite cleverly, I thought at the time, with the simple sentence: “Photographer Nick Ut’s name went in the caption.”

The redacted, or deleted, material begins:

Some time ago when I first joining AP Photos in Saigon back in ’68 (An Outsider in the World of Journalism - in Saigon) , I mentioned ‘Nick’ Ut as working alongside Huan and others in the darkroom. He was the kid brother of Huynh Thanh My, a handsome aspiring Vietnamese actor who took up photography, was hired by AP and tragically killed covering an ARVN operation down in the Mekong Delta back in 1965. (His photo was one of four on our own Roll of Honour on the office wall of staffers killed in the war.)

A photo of Nick Ut’s older brother Huynh Thanh My (left) hung on the AP Saigon’s Roll of Honour here with an annual Buddhist ceremony to honour the dead.

After My’s death, Horst Faas took the young Ut – still just a kid - under his arm and gave him a job in the darkroom developing film and printing pictures. Nick also took up photography and, along with Cung, covered events in and around Saigon. But Horst was very protective and before departing for Singapore a couple years before was quite firm about his covering any combat. “No combat for Nick Ut,” he instructed me – and I’m sure Jim Bourdier too.

Having come to work at such a young age, everyone treated Nick Ut like the office mascot. I never took him all that seriously and certainly wasn’t as close to him as other Vietnamese photographers like Dang Van Phuoc (DVP) and Le Ngoc Cung. He was okay in the darkroom and for ceremonies and stuff around town.

But he was itching to get out there and, during Photo Editor Jim Bourdier’s tenure when I was busy writing and travelling, Ut got into the habit of sneaking off and while never actually getting into combat – well, as far as we knew anyway – he was getting pretty close such as covering the relief operation up Route 13 towards An Loc. He had all the combat gear and stuff, but never sent to cover combat.

Quite frankly, Ut was difficult to manage. I was never quite sure exactly where he was – out taking pictures or chasing the pretty girls.

By early June 1972, the Easter Offensive had fizzled out although some of the territory lost along South Vietnam’s borders, including the DMZ, would never be recovered. The Communists were still capable of launching the odd spectacular battle but life was settling back into its old routine.

One afternoon, I returned from my lunch and siesta slightly later than usual to find the photo office bustling with Jackson Iwasaki from AP’s Tokyo office – a desk reinforcement during the Easter Offensive – hustling in and out of the darkroom printing up film that’d arrived during my break.

Ever-efficient, the experienced old pro was wrapping and drying a handful of black & white prints which he laid out on the desk. “Here, have a look at these,” he said more excitedly than usual. Something dramatic had happened and we needed to decide which one to radiophoto out.

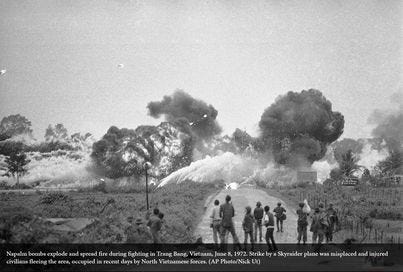

Overnight, the North Vietnamese had cut the main road to the Cambodian border - then known as Route 1 and today’s Route 22 – at Trang Bang, 50 kms northwest of Saigon, most likely to infiltrate its troops out of the nearby Parrot’s Beak into the Cu Chi area and other bases north of the capital.

This border region had been pretty quiet lately and the closure of a major highway so close to Saigon was always a concern. A crew from NBC next door was heading up and Nick Ut hitched a ride. And as word spread, other freelancers also made their way up.

Going through the negatives made clear what happened as the Vietnamese and foreign journalists joined an ARVN unit on the road just southeast of the occupied village dominated by the distinctive tower of a Cao Dai Pagoda, a syncretic home-grown religion based at Tay Ninh further north.

A VNAF, or South Vietnamese Air Force, propeller-driven Skyraider flew low and dropped napalm onto suspected Communist positions inside the village.

Then as the smoke cleared, villagers – mostly women and children - began fleeing down a slope towards the group. Many had their clothing singed black by the napalm and in the middle of the road ran one girl who was completely naked with her arms out and wide-open mouth screaming.

We had several rolls of film of the incident, both Nick Ut’s and those of a couple Vietnamese freelancers, usually official ARVN photographers out making some extra money. As usual, they’d been meticulously logged in with a double set of stick-on numbers – one beside the photographer’s name in an exercise book and the second on the actual roll of film.

The couple pictures Jackson had chosen and printed up focused on the girl – one full-frontal running towards the camera and other from the side as she ran past and more oblique. We both hesitated. AP had a thing – not actual policy – about showing any nudity, even boys and girls.

As I prepared to type up the caption for the radiophoto, I double-checked the film numbers for the by-line. The side shot was from Nick Ut’s film; the full-on shot was from a freelance photographer or stringer.

Then, Horst Faas walked back into the photo office from a long lunch down at Le Royal with his long-time colleague Peter Arnett, who’d also been sent back to Saigon for the Offensive. Horst took a look at what we were doing. I pointed out that we really couldn’t the girl’s naked frontage which even seemed to show pubic hair.

Pointing straight at the picture, Horst said, “No, we will go with this one.” He checked the negative and ordered a tighter crop and sent Jackson back into the darkroom for a new print.

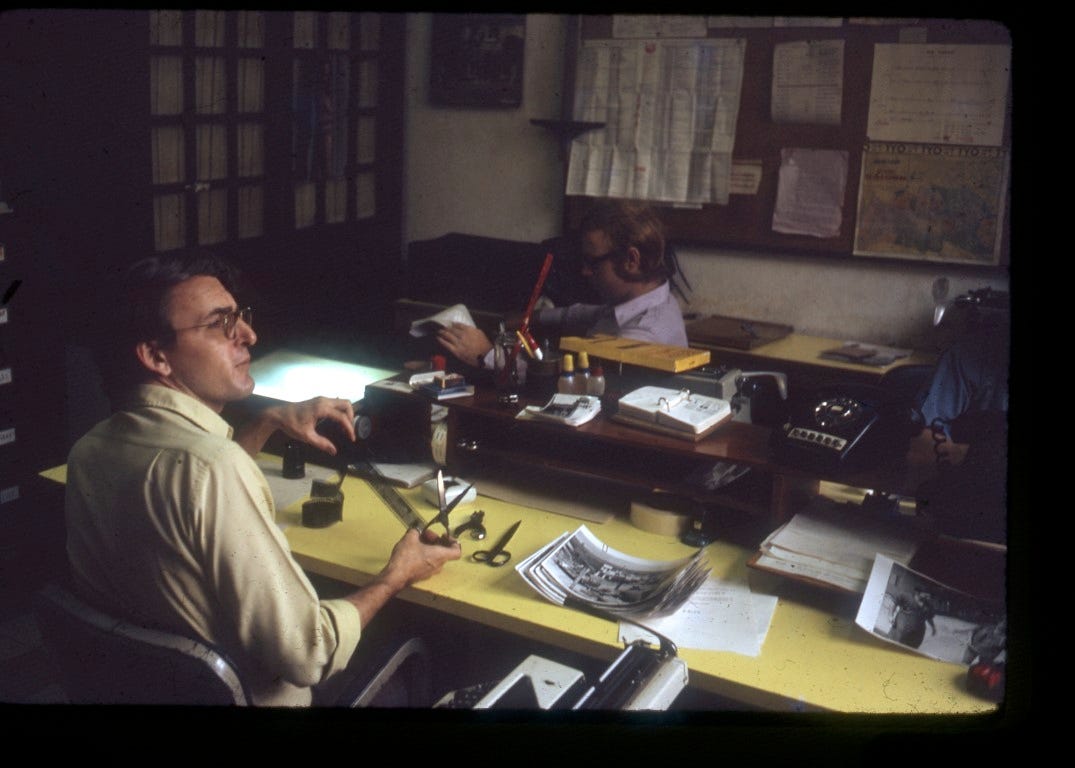

In our well-established style in AP Saigon Photos on the main side of the desk, I began the caption with the initials SAI, for Saigon, a hyphen and then a number; the dateline; the date of June 8; and then a tight three lines about the picture. The grey-painted metal typewriter stand was located perpendicular to the desk and Horst hovered behind me next to the light box.

The working set-up on the AP Saigon photo desk with the lightbox to the left and the log-in book just left of my ashtray and typewriter on a stand perpendicular to the desk. Turned around to my right, this was my position as I typed the caption for the Napalm Girl radiophoto that we’d transmit to Tokyo - and the world. (This photo was taken a couple years earlier.)

As I was finishing typing the caption with the usual (AP Radiophoto) and then the photographer’s byline of “stf/name” for staff or “str/name” for stringer, I glanced over my left shoulder to check the exercise book for the freelancer’s name. Faas leaned down and said firmly in my ear, “Nick Ut. Make it Nick Ut.” Shit! I didn’t argue with Horst. I just did it.

With the caption finished, I pulled the gummed paper out of the typewriter and used a large pair of scissors to cut it down to size for the radiophoto, licked the back and pasted it onto the edge of the picture. We’d already lined up a “cast” to Tokyo and Mr Hung was waiting to drive the picture over to Radio Saigon on his Mobylette where AP’s short-wave radiophoto transmitter was located. Horst took another look at the picture.

Yes, with all the shadows from the clearing napalm smoke, the girl’s openly-visible crotch did seem to have pubic hair. Quickly, Huan was ordered to pull out the office retouching kit and repaint the area a more neutral grey. And with the photo still drying in his hands, Mr Hung headed off.

Job done, I was now seething. I walked out of photos and into the newsroom which had already picked up some of the excitement of our dramatic picture. Along with now-Bureau Chief Richard Pyle, Michael Putzel was a good friend and we’d enjoyed a few pipes together over in Phnom Penh and even slipped out for a few in Saigon too.

I waved for Michael to follow me outside to the open walkway that ran along every floor inside the Eden Building and overlooked a large area open to the sky above the glass-covered ground floor shopping arcade.

Leaning over the waist-high wall, I told Mike what’d happened with the caption. I was pissed off. How could Horst do that? Just ‘cause the guy who really took the picture was just another fucking stringer?

After hearing me out and smoking another Bastos cigarette, I wandered back into the office and glumly took up a seat on the other side of the photo desk. Nick Ut looked a bit stunned as a couple newsmen walked in to shake hands and congratulate him. He sure wasn’t looking at me in the face. All the Vietnamese, including Phuoc and Cung, knew exactly what had happened.

And what was I going to do about it? Well, don’t forget, Horst had hired me out of that Saigon bar four years before. I had not just a wife but now two kids to worry about too. I wasn’t even AP staff yet just this open-ended contract and titles coming and going. Should I make a scene and quit?

Why had Horst done it, I wondered? All I could think – and still even today – was the by-line switch was for Nick Ut’s dead brother. Horst had doubtless carried the guilt of My’s death for years and this was the payback. What’s the harm? He certainly wasn’t thinking of the consequences. (Plus, as I’ve discovered over the years since, this wasn’t the only time Horst did something like that.)

You can sense when a picture’s a winner and we knew the Napalm Girl was another one – just like that one of the police chief shooting the Viet Cong on a Saigon street during Tet ‘68. The picture was an immediate sensation all around the world but stood alone and without a story. Back in the office the next morning, NY was screaming for more details. Who was this girl and what’d happened?

I was assigned to find the Napalm Girl in Saigon’s crowded and often chaotic hospital system. Contrary to what he’s claimed later, soldiers – not Nick Ut - splashed water over the girl and other burn victims and put them into a couple Tri-Lambrettas, a three-wheeled public taxis, for the run into Saigon.

Thankfully, my ex-IVS friend and fluent-Vietnamese speaker Tom Fox wandered into the office and with photographer Cung along, we headed out into the city to find her. Meanwhile, the supposed author of that picture – Nick Ut – was nowhere to be seen. Off again somewhere.

And the published version of my memoir continues:

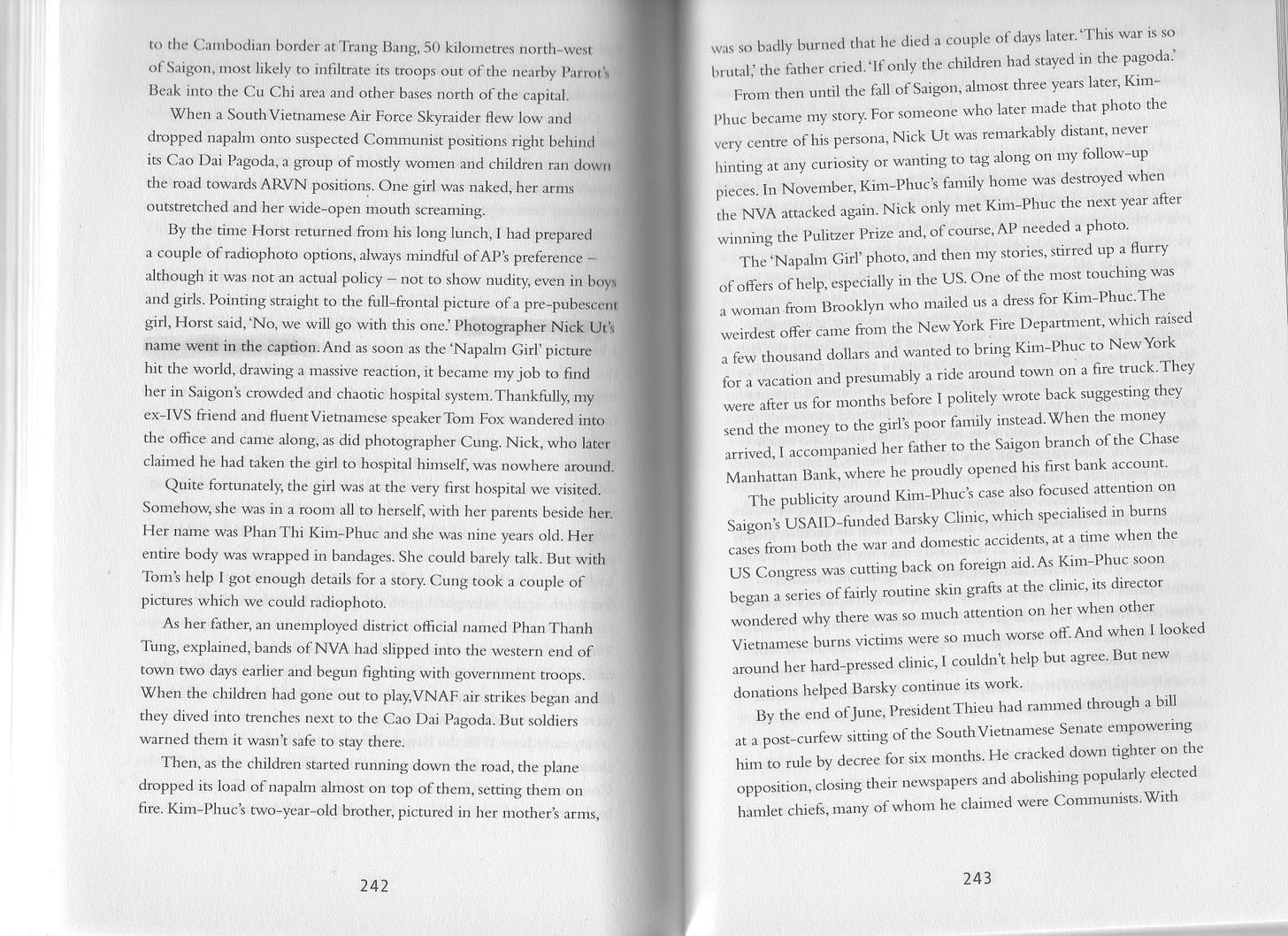

Quite fortunately, the girl was at the very first hospital we visited. Her name was Phan Thi Kim-Phuc and she was nine years old. Her entire body was wrapped in bandages. She could barely talk. But with Tom’s help I got enough details for a story. Cung took a couple of pictures which we could radiophoto.

As her father, an unemployed district official named Phan Thanh Tung, explained, bands of NVA had slipped into the western end of town two days earlier and begun fighting with government troops. When the children had gone out to play, VNAF air strikes began and they dived into trenches next to the Cao Dai Pagoda. But soldiers warned them it wasn’t safe to stay there.

Then, as the children started running down the road, the plane dropped its load of napalm almost on top of them, setting them on fire. Kim-Phuc’s two-year-old brother, pictured in her mother’s arms, was so badly burned that he died a couple of days later. ‘This war is so brutal,’ the father cried. ‘If only the children had stayed in the pagoda.’

From then until the fall of Saigon, almost three years later, Kim-Phuc became my story. For someone who later made that photo the very centre of his persona, Nick Ut was remarkably distant, never hinting at any curiosity or wanting to tag along on my follow-up pieces. In November, Kim-Phuc’s family home was destroyed when the NVA attacked again. Nick only met Kim-Phuc the next year after winning the Pulitzer Prize and, of course, AP needed a photo.

The ‘Napalm Girl’ photo, and then my stories, stirred up a flurry of offers of help, especially in the US. One of the most touching was a woman from Brooklyn who mailed us a dress for Kim-Phuc.

The weirdest offer came from the New York Fire Department, which raised a few thousand dollars and wanted to bring Kim-Phuc to New York for a vacation and presumably a ride around town on a fire truck. They were after us for months before I politely wrote back suggesting they send the money to the girl’s poor family instead. When the money arrived, I accompanied her father to the Saigon branch of the Chase Manhattan Bank, where he proudly opened his first bank account.

The publicity around Kim-Phuc’s case also focused attention on Saigon’s USAID-funded Barsky Clinic, which specialised in burns cases from both the war and domestic accidents, at a time when the US Congress was cutting back on foreign aid. As Kim-Phuc soon began a series of fairly routine skin grafts at the clinic, its director wondered why there was so much attention on her when other Vietnamese burns victims were so much worse off. And when I looked around her hard-pressed clinic, I couldn’t help but agree. But new donations helped Barsky continue its work.

By the end of June, President Thieu had rammed through a bill at a post-curfew sitting of the South Vietnamese Senate empowering him to rule by decree for six months. He cracked down tighter on the opposition, closing their newspapers and abolishing popularly elected hamlet chiefs, many of whom he claimed were Communists. With heavy casualties on both sides, the siege of An Loc was lifted while the counter-offensive to retake Quang Tri, now just a pile of rubble, ground along. The Paris peace talks resumed.

* * *

Back in the US, burglars broke into the Democratic Party headquarters in the Watergate Building in Washington DC, and George McGovern was nominated as the party’s candidate for the coming presidential election. I was annoyed when he mentioned Kim-Phuc in a campaign speech, saying she was running from a school. Didn’t the bastard know what a Cao Dai pagoda was?

At this stage of the Vietnam War, when things were supposedly winding down, no one wanted the dubious honour of being the last Western journalist to die in Vietnam. But up in Quang Tri in July, we lost four colleagues in just a week, including Alex Shimkin, another ex-IVSer and fluent Vietnamese speaker who’d scored a job with Newsweek. The others killed were the Singapore-based and much admired ABC camera crew of Terry Khoo and Sam Kai, and the French freelancer Gerard Arrou.

When Holger Jensen was lightly wounded, the first thing he wanted to know afterwards was if anyone had taken his picture, giving rise to an office joke: ‘Help, I’m wounded – take my picture!’

An even grimmer incident involved a young and fit Britisher named James Gill, who, like so many others, showed up at AP seeking a freelance letter so he could get press accreditation from the military. We did so without much thought, and gave him several rolls of film. He brought back a few rolls of fighting somewhere, and we bought a couple of pictures. Then he disappeared. His Vietnamese girlfriend showed up at the office distraught at not having heard from him. We couldn’t help.

Then MACV contacted AP asking for help identifying the badly decomposed body of a Western civilian found by ARVN troops in the sand dune country south of Quang Tri – the forbidding ‘Street Without Joy’ immortalised in Bernard Fall’s seminal work on France’s Indochina War, and where the historian himself was killed in 1966. He was apparently alone.

One quiet Sunday morning, Mike Putzel and I travelled out to a part of the vast military base around Tan Son Nhut airport we’d never seen before, a huge, high-roofed, tin-sided building that was brightly lit and fully air-conditioned inside: the US Army mortuary. Walking past one stainless-steel table after the other of partial skeletons, skulls and other remnants, we reached the far side of the vast room. We saw a few bones and flesh and fragments of clothing. And there was that distinctive tattoo I’d spotted on James Gill’s forearm. He was a deserter from Britain’s Royal Marines who’d ended up in Vietnam.

Thanks for sharing, as Paul Harvey termed it, “the rest of the story.” Incredible. Just shows that eventually the truth will always out.

Carl, As I understand it, the producers and underwriters of the documentary in question, which counts you as a principal source of the allegations about Nick Ut, are all sheltering behind non-disclosure agreements or whatever you might term self-imposed commitments not answer outsiders' questions about the doc or the verfication procedures that went into it. Such covenants or self-inflicted gag rules are favored by tabloid shows that don't want to answer for made-up things (or politely put, creative license), or by the CIA (once my employer in Vietnam) in the interest of avoiding accountability. Having long practiced television journalism since leaving the CIA I can honestly say that no serious news operation or production I know of would gag its principals in covering a story as newsworthy as the one you claim to have about Nick Ut. Indeed, if the production in which you are involved has such an allergy to candor and full disclosure, no one with an ounce of integrity or interest in truth would or should touch it with ten foot pole. If there are no such constraints on your chosen mouthpiece for these allegations, then open the door and let the light in - put everything that went into it out in public for everyone to examine. I do not prejudge. But until full disclosure is the rule for every participant in the production surely you will understand if you all come across as hot air balloons venting smoke. Again no fair person would prejudge. But the time has come to put up, put out or shut up. Wouldn't you, of all people agree with that? As one who had a role in Vietnam war coverage you doubtless understand and appreciate what makes for seeming bald-faced lies and credibility gaps. FS