My Substack a couple days ago knocking the New York Times for praising a Vietnamese-born buster-bomb maker as a refugee success story drew above-average views, plenty of positive feedback - and more importantly, some insight into the closed but often tumultuous world of the Vietnamese diaspora, what I call the Vietnosphere.

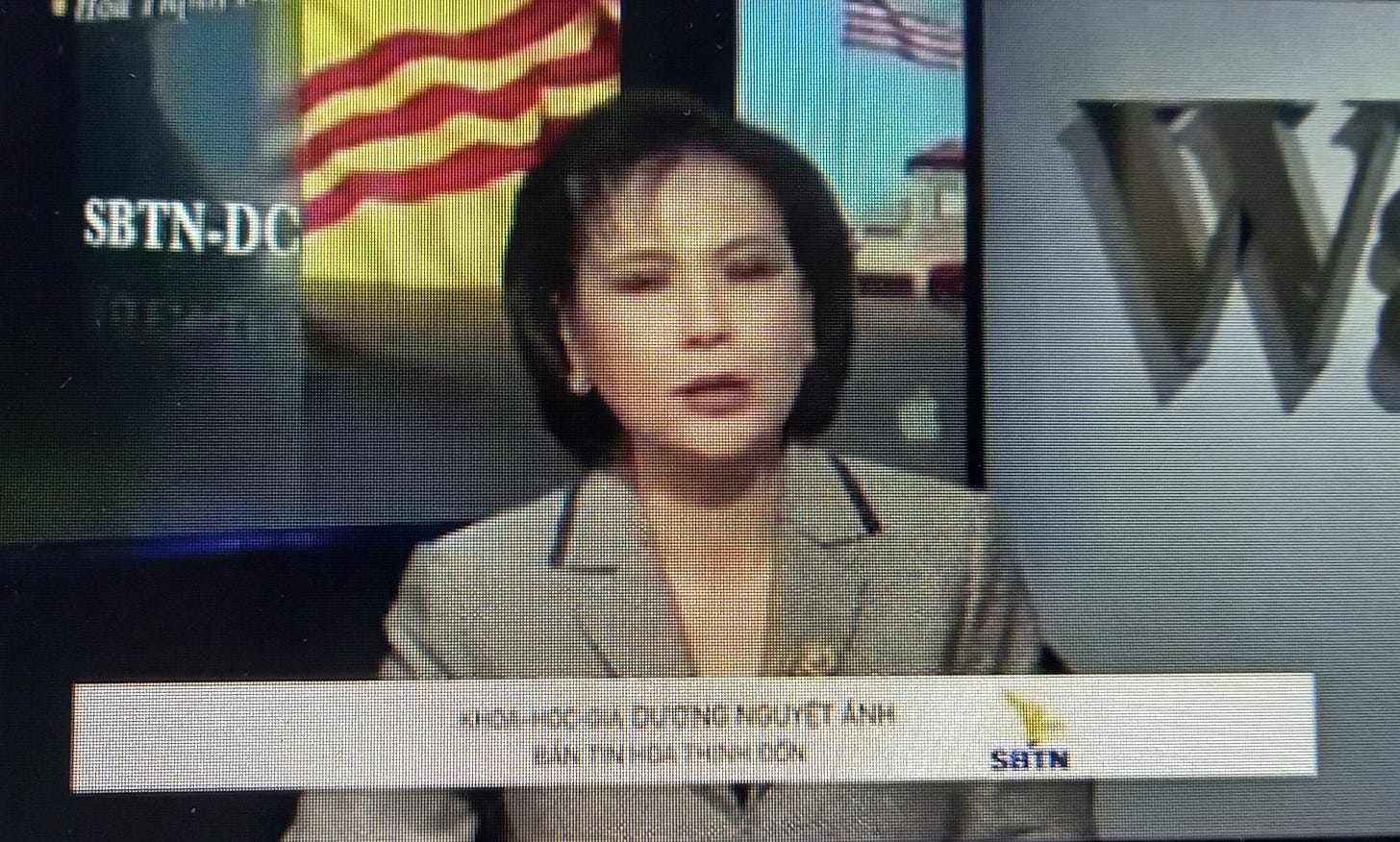

What continues to surprise is how little mainstream coverage grasps the inner machinery of that world. The NYT, for instance, misnames her as “Ms. Anh Duong,” failing to recognize that Dr. Dương Nguyệt Ánh has long been a mythologized figure within Vietnamese exile circles - gala tributes, YouTube documentaries, bootlegged Asia Entertainment specials. She didn’t “break out” into the American spotlight. The spotlight simply showed up late and took an interest in someone the diaspora had already canonised, calibrated, and paraded like royalty.

Having lost the Vietnam War, this community has long been hungry for heroes and role models. It doesn’t just elevate its achievers - it codes them. Figures like Dr. Dương Nguyệt Ánh are instantly sized up: accent (hers unmistakably northern, suggesting 1954 refugee lineage), religious markers (likely Catholic, later linked to Baptist circles), timestamp of exile (airlifted out on her older brother’s helicopter two days before the Fall of Saigon), and stance on reconciliation (she openly condemns those wishing to return, even for brief visits). For those watching closely, it’s identity Morse code.

And there’s another point, often overlooked: Dr. Ánh hails from the most hard-line segment of the Vietnamese diaspora - the branch that fully embraced the American Dream, often alongside deeply conservative politics. Ever wonder why all those South Vietnamese flags were on Capitol Hill on January 6, 2021?

Within that world, exile isn’t just displacement; it’s moral clarity. But much of the broader diaspora, especially outside America, is less doctrinaire. Plenty stay emotionally and physically connected to Vietnam, even under a hard-line regime, visiting family, engaging quietly, refusing to let ideology eclipse lived ties. Dr. Ánh’s rejection of reconciliation puts her at one extreme of a spectrum more nuanced than mainstream coverage tends to allow. The Vietnosphere isn’t monolith. It breathes through contradiction.

To be fair, the NYT does gesture at the familiar arc - the refugee turned scientist, the embodiment of exile resilience and American assimilation. But it does so with the soft glow of admiration, not the sharper lens of context. What’s missing is the pre-existing architecture: how the diaspora already elevated Dr. Dương Nguyệt Ánh into icon status, years before the spotlight swung her way. The paper delivers her as a fresh revelation, when in truth, she was already a well-rehearsed symbol - complete with accent, lineage, moral clarity, and a history of coded reverence within exile circles. And why now, exactly? She’s been retired since 2020.

But this is all as per usual. Mainstream media tends to treat diasporic communities as demographic backdrops, not as the complex, self-sustaining ecosystems of memory, politics, and identity they actually are. Stereotypes abound. Coverage surfaces only when a group becomes useful to a strategic narrative: refugee triumph, culinary novelty, or yes - a potential ally in regime change or colour revolution talk. Plenty of rich, contradictory stories never make the cut.

The Vietnamese diaspora has them in spades. Want to hear some of ‘em? Stick around.