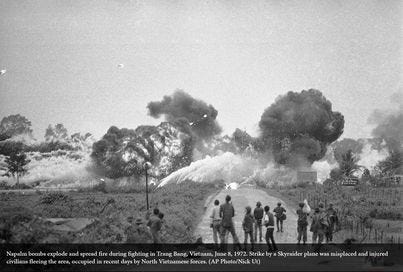

There was another photo that day. No, not the famous Napalm Girl ‘Terror of War’ one - the full-frontal image of Kim Phúc, arms outstretched in pain, fleeing down South Vietnam’s Route One after the napalm strike at Trảng Bàng in 8 June 1972. That photograph, the world knows all too well. It’s now subject of the controversial documentary ‘The Stringer’ - the one my boss at AP in Saigon ordered me to assign Nick Út’s byline. Worried for my job and family, I complied. Meekly, yes. The decision burdened me with years of complicity and guilt, until I finally cleared my conscience.

But there was another photo - my first choice, in fact: a side view of the naked girl running past, flanked by two helmeted soldiers, one on either side of the frame. It was more discreet, more in line with AP’s policies on publishing nudity, even when it came to children. I remember both prints on the desk. I remember going back over the negatives that Tokyo-based photo editor Jackson Iwasaki had developed, edited, and printed. I checked the logbook. As I’ve related many times before, the full-frontal image was from an unfamiliar stringer. The side view, the one I had wanted to run, was logged under Nick Út.

And so - whatever happened to that photo? And the negatives? Now into my early 80s, I’m often complimented on my sharp memory, especially for the details. Just ask the documentary folks, or take a look at the long Q&A responses I gave to AP after ‘The Stringer’ premiered at Sundance in January. They know my story.

But here’s what I still can’t explain: why have I never seen that side shot again? When I finally turned around and looked at all this straight in the eye - back after the photo’s 50th anniversary in 2022 - I couldn’t find it anywhere. Not in the archives. Not in the echoes. And yet, with all the focus on the now-controversial ‘Napalm Girl’ image, maybe no one thought to ask.

Then came AP’s 96-page update on 6 May. I gave it a strong critique - wondering why they hadn’t spoken to a key witness, the stringer’s own brother-in-law, who was right there beside him. Still, I praised one of their findings: confirmation that an Asahi Pentax - not a Leica - took the image. Something I’d long suspected. Nick Út, they now said, was merely a “possible” photographer.

There was a lot to absorb in that report. But I couldn’t help noticing: the side-view photo wasn’t on the contact sheet they published - neither among Nick’s black-and-white nor colour frames from Trảng Bàng. And then came the twist. After AP studied the NBC network’s footage - material the documentary makers couldn’t obtain - they introduced a new figure into the scene: Huỳnh Công Phúc, a South Vietnamese military photographer on the right side of the road as Kim Phúc and the children ran past. Gosh. What a surprise!

But that was just the prelude. Barely ten days later, on 16 May, World Press Photo dramatically suspended Nick Út’s byline for the image now known as ‘The Terror of War’ and its 1973 prize winner, bringing the controversy squarely back into the mainstream media with even me slipping out of the narrative. Út’s defenders responded with full-scale condemnation. While not claiming to know definitively who took the photo, an open letter signed by more than 400 photojournalists declared that “accusing someone without irrefutable evidence, and making a decision to strip the attribution is unwarranted, unreasonable and just plain wrong,” and demanded Nick Út’s reinstatement to its honoured ranks.

I had my own reactions - annoyance, mostly - reading the WPP report. For all its detail, it felt just as institutionally bound as the AP’s. Despite everything, it still refused to say definitively who took the photo. Instead, it floated two possibilities: Nguyễn Thành Nghệ, whom together with the documentary team I’d tracked down and apologised to two years ago - someone I’m personally convinced is the real author, as is the documentary - or this newly introduced figure, Huỳnh Công Phúc - the South Vietnamese military photographer AP identified from NBC footage. That’s quite the spread. And quite the cop-out.

It wasn’t until I read AP's May report and saw Phúc’s name - this previously unidentified figure on the far right of the road - that something clicked. A light bulb moment, as they say. We now know Nick Ut was way out of position down the road. What if Phúc took the side-view photo? The one I remember so clearly on that desk in Saigon. The roll of film logged under Nick Út’s name. It would explain the vantage point, the absence on Nick’s contact sheets, the persistent uncertainty. And yet - neither AP nor World Press Photo ever asked me about Phúc. Not in the detailed back-and-forth I had with AP. Not in WPP’s latest and much more lengthy report released on 26 June. I was never interviewed. So how could I have spoken up?

Well - here, I suppose. Although the documentary filmmakers are updating the film so it may well appear in the final version.

I’ll admit, I thought it was all over in May. When World Press Photo suspended Nick Út’s byline, it felt like the final act. But then - on 26 June, and much too quietly - came the the full, independent report commissioned by WPP. Thorough, yes, and well worth your while to read, but still limited in scope. All credit to them, although its focus was entirely on what happened at Trảng Bàng - not what happened back at the AP office. Still, after all the analysis, all the spatial reconstructions and archival deep dives, it came down to the same two names: Nguyễn Thành Nghệ and Huỳnh Công Phúc. The same uncertainty. The same refusal to decide.

This time, there was no media coverage. No headlines. More criticism from Nick Ut’s supporters, even a t-shirt fund-raiser. Just the quiet thud of a report that tried to clarify and, in doing so, confirmed what many of us already knew: that no one wants to be the one to say it. The caravan, it seems, has already moved on.

But maybe it’s not over. Not entirely. Thanks to World Press Photo’s own investigation, we know more about Huỳnh Công Phúc - the man I now believe took that side-view photo. He stayed in Vietnam after 1975, kept working as a photographer, and reportedly died on assignment in the Mekong Delta. But his family must still be out there. And if they’re anything like the photographers I’ve known - who never throw away their negatives - maybe, just maybe, that missing frame still exists. The one I saw on that desk. The photo I’ve never forgotten.

Pictured at the front of the photo by Nick Ut himself, Huỳnh Công Phúc (1937–2009) was a Vietnamese photographer, reports this extract from the WPP-commissioned independent report. He died at age 72 in the Mekong Delta’s An Giang Province during a photo assignment, after a motorbike accident while carrying heavy camera gear in 2009.

Though often misidentified online as Nick Út, Phúc is visible in archival footage at the front of the scene near Hoàng Văn Danh, beyond the barbed wire. Danh later told the VII Foundation he did not know the other individual’s name. A comparison with Út’s own photo confirms that the man in question could not be Út, as he appears in the frame. Visual differences in clothing, build, and stance further rule this out.

Both the VII Foundation and photojournalist Michael Ebert independently confirmed that the individual is not Út. In April 2025, AP relayed that, according to UPI photographer David Hume Kennerly, the person was identified as Huỳnh Công Phúc — whose presence at the scene and position at the frontline raise the possibility that he, too, may have taken the iconic photograph.