It’s gotta be an expat’s worst nightmare.

You’re an American who’s spent fifty years in Japan, a widower from a bad marriage with an estranged daughter who never learned your language. After a two-year dating scam, you've lost everything—even the phone that tethered you to old friends. Forced to sell your Tokyo apartment to repay the debts, you’re whisked away—virtually kidnapped—by your daughter and placed in an aged care facility in unfamiliar Nara. You have delirium and dementia. You don’t even know where you are. You barely speak the language.

And let that be a caution to anyone dreaming of a quiet expat retirement.

Hearing this news about my long-time friend Carl over the past week has saddened me. We’re the same age, 82. I’ve lost more friends than I ever had. During the Vietnam War, killed like photographer Ollie Noolan and disappeared like Sean Flynn. And those afterwards, like Tim Page—suddenly, and quickly—from pancreatic cancer. All those other friends too, gone. It’s also made me realise how few real friends you truly have in life. In backstabbing journalism, you’ve got plenty of chortling colleagues, but few friends indeed. Everyone’s got stories of family—parents, spouses, partners—needing care. But a lifelong friend far away in another country, fading without you... well, that’s a different sorrow altogether.

The Other Carl and I go way back—to 1961, that first day in Freshman English at the University of Redlands. Readers of The Bite of the Lotus might recall him scattered through its pages, a constant presence over the years and continents. One of those small Southern California liberal colleges like Claremont, Whittier, and Pepperdine, tucked up against the San Bernardino Range, far to the east where LA’s smog drifted by sundown - murky, orange-grey, and doom-scented over the town’s stereotypical lines of top-heavy palm trees that never fall over.

Another Carl. Not such a common name, really, unless you're a villain with a K in a 007 movie. We laughed and shook hands, then sat side-by-side in Freshman English class just to confuse the teacher. When questions came, we’d glance at each other with a grin and silently decide who’d answer. He was a relentless joker—the opposite of me. Finding his serious side was nearly impossible.

He majored in English. Me, the new field of International Relations and ambitions of becoming a U.S. diplomat. For compulsory Phys Ed, he ran cross-country. I played co-ed Badminton. But we clicked immediately, tagging along to football games the university rarely won, parked in the top rows of the bleachers, hurling reckless one-liners that cracked up everyone below.

One of the University of Redlands’ real strengths was its exchange and study abroad programs—with semester offerings in Washington, DC, and Salzburg, Austria. I was curious enough to take German for a year, nearly flunked it, and watched my GPA tumble. Besides, The Sound of Music never did speak to me. Then, midway through sophomore year in 1963, during one of our weekly—again, compulsory—Chapel sessions, a senior student spoke about his year at Chung Chi College in Hong Kong—and something sparked.

My first love was still Africa—specifically the former Belgian Congo, where I’d grown up until I was fifteen. By now it was Mobutu’s turbulent Zaire. My folks had returned there the year before after doing their bit for the civil rights movement at a Methodist church in Los Angeles, leaving me behind. I dreamed of going back myself, maybe through JFK’s newly created Peace Corps after graduation.

Asia? I hadn’t thought much about it. Just scraps from World War Two history, the Korean War and stuff going in a place called Laos. Monks were burning in South Vietnam. My pacifist parents had once wanted to be missionaries in Japan —after Hiroshima and Nagasaki—but families weren’t permitted by the U.S. occupation authorities and got the Congo as a sort of second prize. I also can’t say I knew much about Chinese food beyond Chop Suey and Chicken Chow Mein.

And so afterwards, Carl told me he was applying for the university's formal exchange position in Hong Kong. Half-heartedly, I did too. He got it—I didn’t. But that day’s speaker also let me in on a little secret: I could apply directly to Chung Chi College. “It’d probably be much cheaper too,” he explained. Carl had to keep paying his tuition at Redlands to support the incoming student from Hong Kong, while a direct applicant like me could bypass that entirely. “Your biggest cost would be the airfare getting there and back,” he said.

So I applied directly, got accepted, and spent the summer working to scrape together the money. Through the British Consulate in LA, I applied for a student visa. And, quite ominously, I needed my Draft Board’s permission to spend a year overseas—a legal hoop everyone had to jump through back then. Just for good measure, they asked me to justify the Conscientious Objector status—the subject of a future Substack, by the way—that I’d ticked off the year before when registering for the military draft. And that took some serious head-banging writing, especially since I’d gone a bit wobbly on the religious grounds required at the time. I got permission and my 2-S student deferment held. But the Draft Board issued no ruling on my CO.

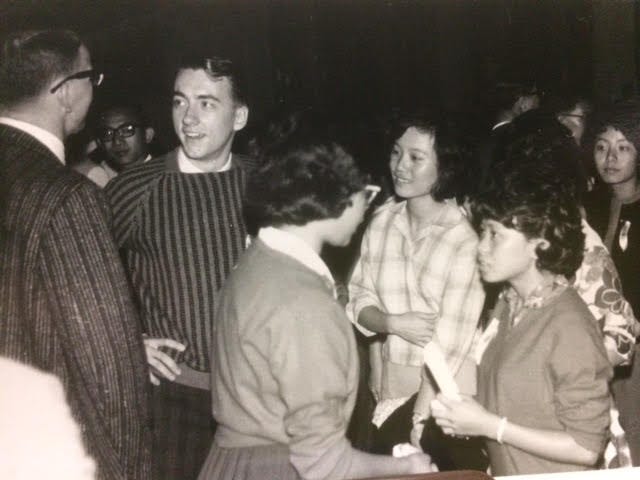

Carl and me after Chung Chi College’s annual To Lo Harbour swim with some of our Chinese student friends, most of them from overseas Chinese communities in Sabah (North Borneo) and Sarawak and, with more assured future, a lot more ready to have fun. The Other Carl did a much better job of keeping in touch than me, off to South Vietnam.

And so came our introduction to Asia as we took on Hong Kong together. Constant companions. Memories for a life-time. Chung Chi College—a remnant of pre-Communist China’s 1949 missionary-run university system—was tucked out in the then-British colony’s vast sparsely-populated New Territories, beside the main rail line to Guangzhou (formerly Canton), near To Lo Harbour and past Sha Tin, with a soaring mountain chain to the south.

I’d arrived late, tangled in visa delays and a typhoon delay to our JAL DC-8 in Honolulu. Classes had already begun, and Carl—whose knack for making friends never failed him—was already settled. He helped me navigate the noisy dorm life, where morning wakeups came not from alarms but from throat clearing and noisy noodle slurping right beside me. (I quickly learned to get up and out the dorm before them.) Later at lunch and dinner came the mob scene of round-table communal meals, where I earned my chopstick stripes in record time or nothing to eat. The food was totally lousy—and as I recall from an unpublished stretch of memoir:

By the end of that first week at Chung Chi, I was ready for a serious Chinese meal – and a group of Overseas Chinese students invited Carl and I for the short train ride down to Sha Tin and its many open-air seafood restaurants. Ah, what a pleasure! The orchestrated chaos of yelled-out orders, ladles banging around woks and calls for more bottles of Carlsberg or San Miguel beer. Mostly from Malaya’s Sarawak and North Borneo (Sabah), the students spoke better English and with financially-assured futures much more care-free than local students whom I’d already noticed took their studies very seriously. Away from home like us and at loose ends during holidays, they became out closest companions, along with a handful of Hong Kongers.

Getting down to the city on the KCR—Kowloon-Canton Railway—was always a treat on the rickety diesel-pulled train, slamming all the windows down from the soot through the tunnel under Lion Rock Hill and down a couple stops before finally pulling into Tsim Sha Tsui right at the tip of the Kowloon Peninsula overlooking Hong Kong Harbour.

The sight of this magnificent harbour still takes my breath away over 60 years later. But back then, the setting was much more unhurried and in a British Colonial-era time capsule. With its clock tower and distinctive dome, the Kowloon Canton Railway’s two-storey colonnaded grand terminal building dominated the northern side of the harbour right at the water’s edge. The Star Ferry was a quick walk away past a busy terminal of rickety single and double-decker buses and long queue of taxis, all British-made vehicles out a Dinky Toy collection.

Just up Salisbury Road past a small military compound stood the white-fronted Peninsula Hotel, the colony’s grandest hotel, with the YMCA next door – a fascinating juxtaposition. At the first intersection, Nathan Road headed north through Tsim Sha Tsui’s tourist and shopping district then dominated by endless small shops without a brand-name outlet in sight. On a side street not far behind the renowned hotel was a restaurant run by White Russians who’d sought refuge first in China and then Hong Kong. For only a few local dollars, we could enjoy a meal of borsch and fresh Russian-style brown bread and butter – and soon our favourite stop on our trips into the city. (During the year, hundreds more White Russians arrived from northeast China and were put to work on public works projects before migrating to other countries.)

And that magnificent harbour was like something out of a Joseph Conrad novel.

Before the massive land reclamations of later years, Hong Kong Harbour was much larger. And before the age of container ships and super tankers, its dark-green waters were dotted with dozens of smaller freighters like that old Victory ship I’d taken back to Africa in 1954. Like suckling pigs, wooden junks, barges and walla-wallas, or large roundish sampans, surrounded the freighters unloading their goods with on-board winches and hauling them to godowns, or warehouses, on-shore. Just around the corner and north of the Star Ferry was the main passenger terminal for ocean-going vessels such as those from American President Lines on the trans-Pacific run to the US West Coast – a tempting trip I was never able to do. The terminal was also where – only months later – I’d catch a French paquebot down to Saigon on my first trip to South Vietnam. Hong Kong Harbour had its own heart-beat and I was totally entranced

Carl should’ve been talking to that lovely young student next to us at one of many student functions at Chung Chi College and which became part of the Chinese University of Hong Kong in the academic years of 1963-64.

And Carl and I were right into everything. Penny pinching students on a budget. Happy for a free meal, especially yum cha (literally ‘drink tea’) when it was still genuine. The female students at Chung Chi were mostly plain, bowl haircuts and daggy classes, and we’d wander into Central on Hong Kong Island to perve at the office girls in their split high-collared cheongsam. Sometimes just sitting in plush hotel lobbies for a change of scene. Neither of us were very sexually experienced and couldn’t afford the fleshpots of Wan Chai in any case and Carl constantly joked of his FSU, or frustrated sex urge. We settled for Saturday tea dances although I later got a girlfriend and he didn’t. Kurosawa movies. Weekend hikes over those mountains. Beach barbecues with those Chinese friends. An overnight ferry over to then-Portuguese Macau drinking cheap plonk.

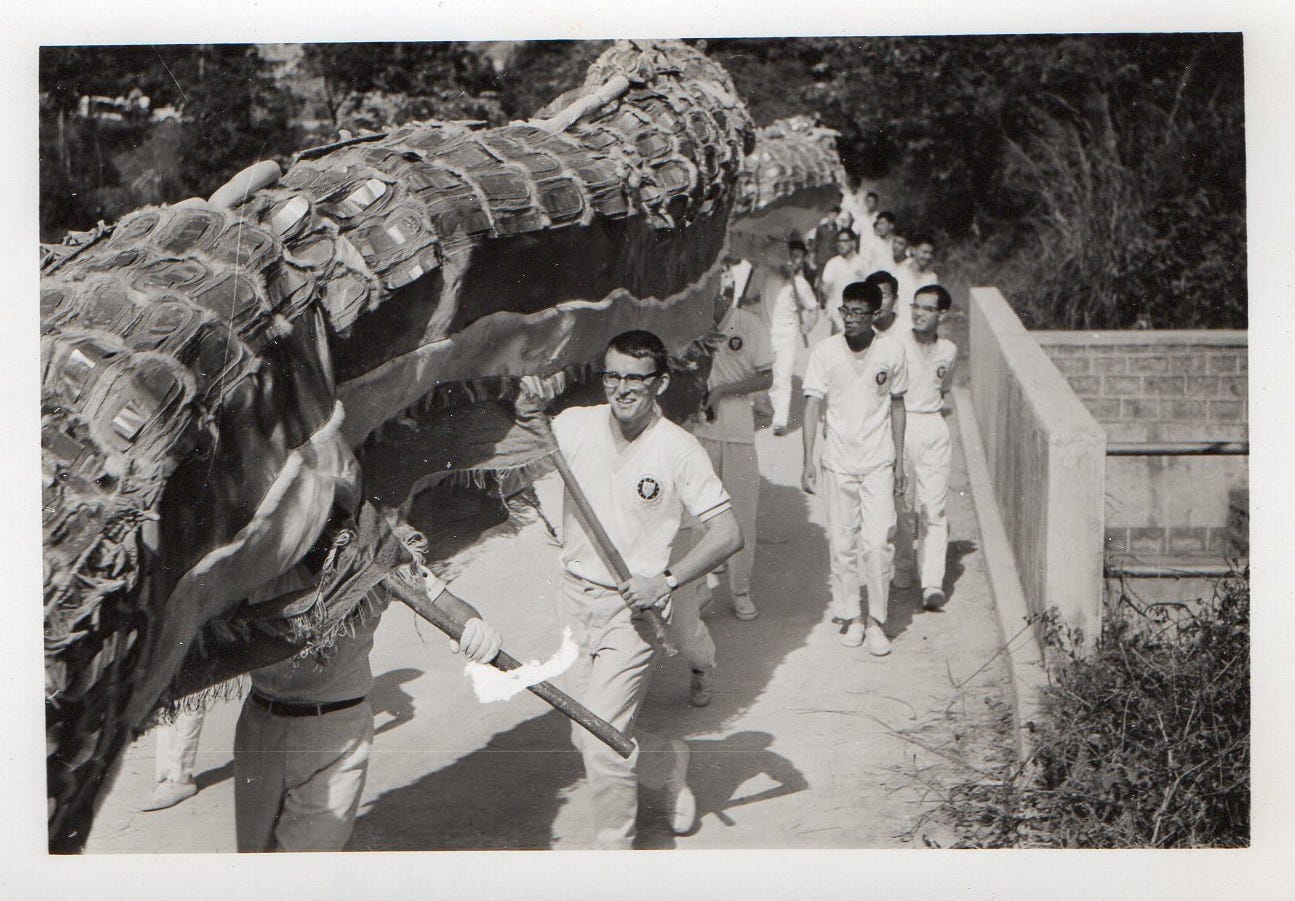

I was part of the college’s Dragon Dance to celebrate the inauguration of the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Shortly into the school year and with great celebrations, Chung Chi was inaugurated as part of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. But the college offered a limited slate of English-language courses in its History and Geography department. I wasn’t attempting Chinese, and with plenty of independent study, I had more time to absorb the news—especially the mounting turmoil in South Vietnam, only a few hours’ flight away. A military coup had overthrown President Ngo Dinh Diem back in November, and, encouraged by a Time magazine correspondent I met through one of my professors, I decided to head down there by ship during Chung Chi’s month-long Chinese New Year break—a pivotal decision that would change my life. I heard later Carl was disappointed I hadn’t invited him, but in hindsight, just as well; we’d have been playing and joking around too much, and what unfolded demanded seriousness. By mid-1964, I was back in South Vietnam with USOM—and the rest, as they say, is history.

After that intense year in Hong Kong, the Other Carl and I were friends for life—those memories always there to tap into, often with laughter. That shared introduction to Asia wouldn't have happened without the friendship. Carl headed back to Redlands to finish university; I followed a year later to complete mine. After failing to get into grad school, I returned to South Vietnam with USAID in mid-1966. We kept in touch, as one did back then, by the occasional letter. Then came the surprise—Carl turned up there too, serving with IVS (International Voluntary Services) for his ‘alternative service’ as a Conscientious Objector, a conviction I don’t recall us ever discussing. He was stationed way up north in Danang teaching English, while I was down in the Mekong Delta.

We finally crossed paths again after the Tet Offensive in early 1968—a far scarier ordeal for him than for me in quiet Go Cong province. By then, I’d quit USAID in protest and landed a job as a photo editor with the AP in Saigon.

Reconnected by a schoolmate from my missionary school days in the Congo and fellow IVSer, Bill Robbins, Carl dropped around our little love nest one evening for what was literally a mind-blowing evening as I describe in The Bite of the Lotus: an intimate memoir of the Vietnam War.

After meeting Kim-Dung and sharing a pleasant home-cooked meal with us, Carl asked if I’d like to try some marijuana. I enjoyed the odd Filipino cigar but had never been a smoker. As I looked on with interest, he unravelled a cheap Vietnamese filter cigarette, mixed the tobacco with some flaky green vegetable matter and deftly dropped them back into the empty cig, twisting it closed. He lit up, had a toke and passed over the joint.

My first-ever dope was pretty mild, but I sure got the idea. The switch was thrown. The music sounded different, with greater clarity. The psychedelic posters on our living room wall, which I’d picked up in San Francisco, became more vivid. The night sky outside our wide-open door and window seemed darker than usual. I heard every sound down our alley and out into the deserted street.

I also felt afraid. Those nightly booms out in the countryside sounded mighty close. But my brain went into an overdrive I’d never experienced. It was all terribly profound, of course. Somehow, everything made more sense, even the tragic folly of Vietnam. If only we could get that handful of folks on both sides running this war to smoke a joint together. I felt happy. Then the munchies came on. When Carl crashed on the couch, I headed upstairs to a passionate night of stoned lovemaking with Kim-Dung.

And so—better and worse included, addictions among them—the Other Carl introduced me to weed, grass, dope, whatever you call it. I kept on with my Vietnam life, anchored by Kim-Dung, eventually winning her father’s permission to marry, and dragging myself through that dull AP job through late ’68 into ’69. With his draft troubles behind him, Carl happily headed off to Indonesia. After some time knocking around Jakarta, he landed in Jogjakarta, the old royal capital. Following Laura’s birth that in early September 1969, I came down for a visit.

In Vietnam, new mothers traditionally return to their parents’ home for the first month after giving birth. I flew out on R&R to Singapore, then on to Indonesia, where I pleasantly reconnected with Carl, now embedded in Jogjakarta’s art scene. We never made it to Bali.

That became a running joke—never got to Bali. Still is. Even today, when Bali’s a top Aussie holiday spot and title of a catchy song. Carl had fallen into the local art world, and into unrequited love with a woman he never stopped talking about. We spent our days getting high and him trying to teach me how to make batik cloth. Borobodur, the world’s largest Buddhist temple outside the city, was a memorable highlight with no other tourists around.

And then came the first of much longer gaps in our life-long friendship. By early 1973 and our home leave after the Paris Cease-Fire Agreement, Carl was hanging out in Berkeley when we bopped in for a momentous moment in recent American history, the Watergate Hearings that led to President Nixon’s resignation the following year:

We then hit the road from Denver, catching up with my old friends Carl and Bill in Berkeley. The US Senate’s Watergate hearings, which would ultimately bring down President Nixon, were just starting, so we spent days watching the proceedings live on TV.

Carl was getting an advanced credential for teaching English and planning to move to Japan where caught up with him again, some readers might recall, in Tokyo after the Fall of Saigon, ending up on Guam and ordered back to the U.S. by AP in June ‘75.

And so we headed home to America. Using my AP-issued Air Travel Card, I booked First Class air fares for our entire mob. Then, claiming direct flights to LA were fully-booked, we travelled on Japan Air Lines up to Tokyo where I caught up with AP colleague Ed White and heard his evacuation story from over the fence at the American Embassy and hung out with my old university pal Carl, now teaching English, and my Aussie CBS cameraman friend from Cambodia Norman Lloyd. Dropping by Norm’s Japanese-style home one evening, we sneaked up into his attic for a much-enjoyed joint in drug-tight Japan – and hiding from his anti-dope South Korean pianist wife.

During that last visit, Carl was settling into Japan—now fifty years ago—and the gaps between us grew wider, filled only by occasional letters or news through mutual friends. He was teaching English at a university. We finally met again in late 1997, when I flew to Tokyo for the launch of the Japanese-language edition of Requiem, the album tribute to the 200+ photographers from both sides lost in the wars of Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos between 1945 and 1975. We caught up in Shinjuku, Carl cracking jokes as always. But when I asked about his marriage, the mood shifted. He told me, dead seriously, that his wife hit the off switch as soon as their daughter was born. No affairs for him, but he always looked forward to summers down to Cambodia to tame the old FSU, usually combined with a conference or two. Somehow, they stayed together.

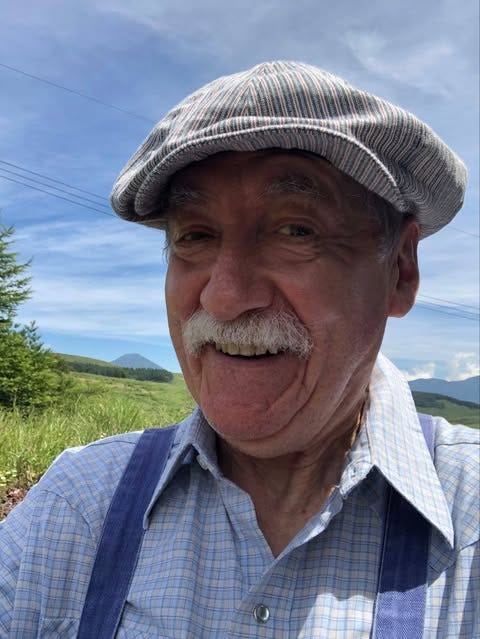

With his distinctive moustache, Carl got into a string of acting jobs after his retirement as an English professor.

With our now regular returns to Vietnam from Australia, the challenge became syncing up with him during his near-annual jaunts—a constantly shifting target. We met up briefly in 2010 and 2015, a year after his retirement and after his wife Hiromi death after a long illness. Remarkably, and very unlike me, he didn’t seem to care about news and what was happening in the world. Just having fun and always a keen walker. And as social media grew, especially Facebook Messenger, we always kept in touch. He was on a pension from his university, but only paid up every couple months forcing him to budget carefully, but also picked up gigs as a moustached Western actor in feature films, TV series, music videos and commercials—sometimes even moonlighting as Santa Claus. Always great pictures. Beautiful locations.

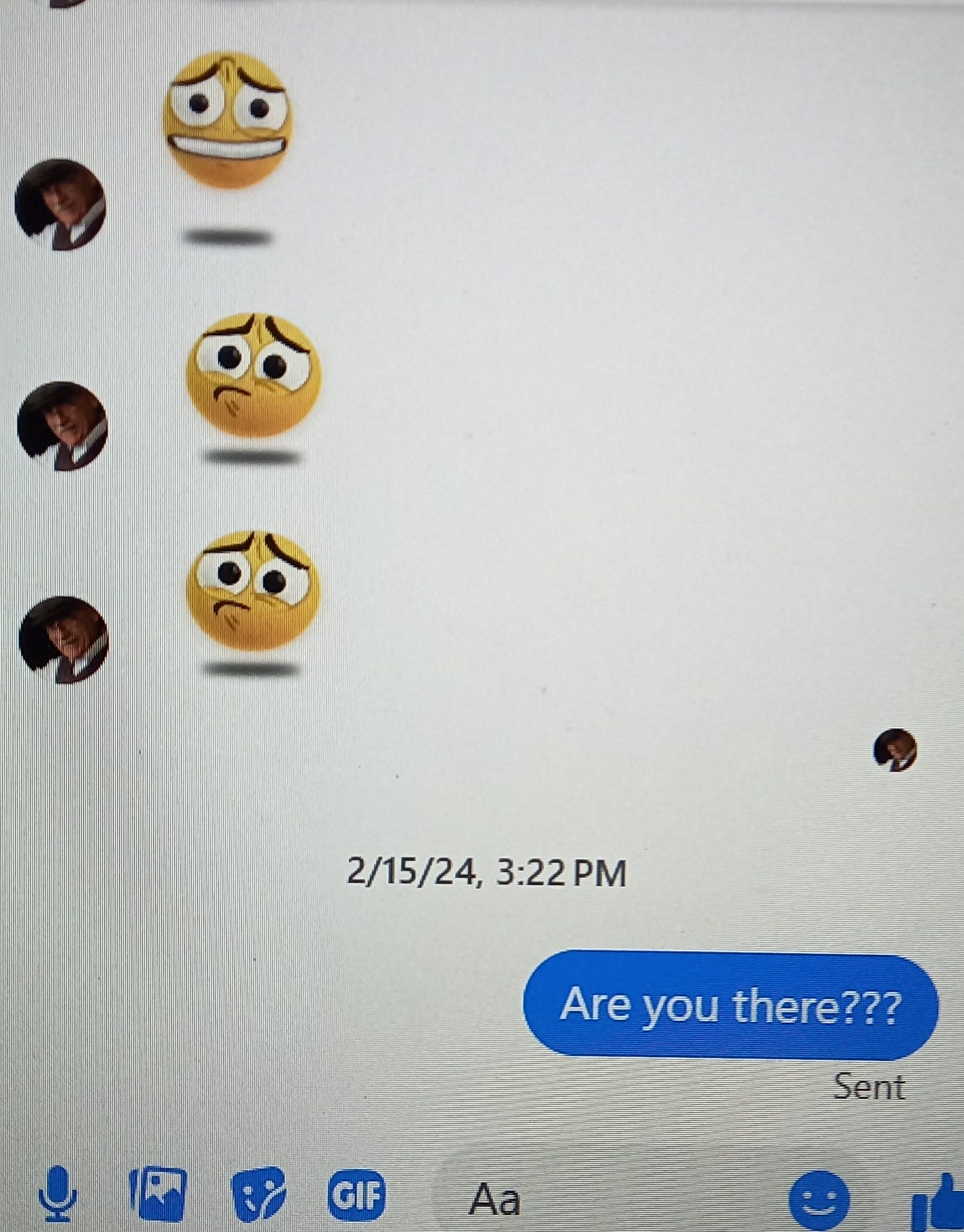

Occasionally he'd send views of Mount Fuji from his apartment in Tokyo’s far northwest suburbs. We again reunited in Vietnam in 2019, just before COVID, meeting up in Saigon and later in Hanoi with his Cambodian companion So Phea. Carl was ever the joker and clown. Afterwards, and through the long lockdown stretch, we kept chatting on Messenger—long exchanges punctuated by his relentless feed of lively emojis.

When travel to Vietnam finally resumed with our first return in late 2022, I reached out to Carl on Facebook—lured by VietJet’s inaugural low-cost flights and the chance to reconnect. Something felt off. By early the next year, his messages took on a giddy tone, like a man newly in love. It was all secret, he said, but he’d tell me soon. A half-Japanese named Laura woman in her early 40s. “Still top secret,” he added, punctuated by happy, bouncing emojis.

Then came a message from a drugstore—he’d run out of credit and hadn’t paid his phone bills. “Too many loan sharks,” he wrote. More troubling still: his U.S. passport had expired, and he couldn’t afford the renewal. He mentioned a cryptic note sent to his older brother Ted in the Bay Area which I never saw—and signed off with one final string of bouncing emojis.

That was the last I heard from Carl.

Early the next year, Phil—our mutual friend from Redlands, who’d backpacked through Hong Kong when we were there—was passing through Japan and asked for help tracking him down. But Carl didn’t reply on Messenger. And there wasn’t time to head out to his distant suburb. He’d dropped off the grid entirely.

Nobody knew what had happened to the Other Carl.

Then this last April as part of our return to Vietnam for the 50th anniversary of the Fall/Liberation of Saigon, we were flying on up to Tokyo—my first time since 1997 and Kim-Dung much longer—with our Saigon family for a week before those festivities around the 30th. Phil had caught up with Carl in 2023 before he’d disappeared—and passed through Tokyo from his home in Honolulu the month before, reaching out to his daughter Mika but received no reply.

I told Phil of my upcoming trip and we exchanged a burst of messages with his wife Jaynie contributing Carl’s Facebook contacts all the breadcrumbs she could gather from his earlier posts, including his favourite local noodle shop. We couldn’t file a missing person report—not in Japan, where only family can do that. And then, most ominously, word reached us that Carl had been caught up in a dating scam—most likely catfished. He’d lost everything.

I knew I needed more professional help. I remembered hosting a Japanese aviation journalist, Koji Kitajima, during his visit to the HARS Aviation Museum, where I volunteer. I reached out, explained the situation, and asked if he could help—even just to confirm with local police whether Carl was still alive. Koji responded immediately. He’d already contacted Mika and cleared his schedule to accompany me to Carl’s suburb the day after our arrival.

One email from Koji revealed he'd tracked down Carl’s favourite noodle shop—now closed—but the owner remembered him. Another message said Carl had visited a local elderly assistance organization for help at the beginning of the year. Proof that, at least recently, he was still alive.

I couldn’t have asked for greater help than Koji provided the day after our return to Tokyo, staying in busy Shinjuku. Something had happened to Carl’s old mobile—he’d lent it to a mysterious Nepalese man—and Mika had mailed Koji a new SIM card in hopes of re-establishing contact. A new phone she’d sent never arrived. And with Tokyo’s labyrinthine train system and sprawling stations, I’d have never reached Carl’s suburb on my own. I was so nervous, I even left my Aussie Akubra hat on one transfer. Koji was straight on the phone and tracked it down—a lovely (and very honest Japanese) footnote to our story.

Two hours away in Tokyo’s outer suburbia, we could’ve been anywhere in modern sprawl. Flat landscape. A shopping plaza. Wide streets. Low-rise homes and shops. We had Carl’s address. A distant apartment block was our target—no sign of Mount Fuji, just a 15-minute walk. The lift to the seventh floor. A knock. And there was Carl: clearly alive, calm, almost like he’d been expecting us. The apartment was a mess, and he was busy in the living room sorting through old cell batteries to see if any still worked. Right away, and to my surprise, he started reminiscing fondly about his late wife Hiromi, pointing to a dusty ancestor shrine in his adjoining bedroom.

I could always get a bit bossy with Carl, so I made him clear a couple of chairs for us to sit down—dammit. “We’ve been worried about you. Everybody. All your old friends. What happened? What’s this about a dating scam, for gosh sakes?”

He replied calmly, making clear eye contact, and spent the next fifteen minutes telling the story. He’d met a woman named Laura—but only once. She’d claimed to be expecting a windfall and needed help. There was always going to be another meet-up at Starbucks in the Ginza, but no one ever showed. He kept pitching in via Apple Pay, stopped paying his phone and electricity bills. “And then one day—Sayonara,” he said.

“Well, how much do you owe then?”

“Oh, four million… or was it forty million? I can’t remember,” he shrugged, confident that selling his apartment of forty years would fix everything. He and his Nepalese friend would find somewhere to live, he explained.

“And when’s the sale?” I asked, looking around at the mess.

“Oh, in a couple of weeks. But it’ll be all right.”

Then came the kicker. “And what’s more,” he added, with a spike of anger, “my daughter and her husband aren’t gonna get any of it.” He went on at length about how opposed he’d always been to their marriage. “The money’s all mine.”

We handed over the SIM card Mika had sent to Koji, and I told Carl firmly: get your phone back, get back online, and onto Facebook—let people know you’re still here. He muttered something about it not being the same number, his accounts wouldn’t work, and all that. Koji and I weren’t having it. “Just do it,” we said. “You can sort the numbers out later.”

After about an hour, I asked if he wanted lunch. We left the apartment and made the long walk back toward the shopping centre and train station, heading to his favourite chain restaurant. A smorgasbord of dishes fit to feed an elephant—order by writing numbers on a sheet, get your own drinks. Koji and Carl liked the same dish. I wasn’t that hungry—just drained. Carl, though, was ravenous, like he hadn’t eaten for days. And maybe he hadn’t. He even polished off my leftovers.

We reminisced about old times, and I urged him to come into Shinjuku before we left—to see Kim-Dung, me, and the family whom he’d last met in Saigon. I thought about giving him some money. But decided not to.

In the glary mid-afternoon sun, we said goodbye at the train station, half-hopeful I’d see him again in the next couple of days. Koji and I travelled to another station to retrieve my Akubra, then continued the long run back into the heart of Tokyo. I thanked Koji for everything, feeling quietly philosophical. “Well, even if nothing more happens, I did my best. I found my long-lost friend. Thank you.” We parted ways before Shinjuku—he headed home, and I went on to catch up with the family. I felt satisfied. Carl was still with us. I messaged Phil and the others to let them know.

I had to wrap up my Tokyo visit and fly back to Saigon ahead of the rest of the family for the 50th anniversary events the Ministry of Foreign Affairs was organising for those of us who’d covered the Vietnam War—and, they reckon, helped them win it too. Still hoping for some kind of update from Carl, I stopped into a Nepalese-run grocery store in North Shinjuku on my final morning. The cashier called the man who’d been given Carl’s old phone. Contrary to what Carl had claimed, his English was perfectly fluent. He assured me he’d return the phone right away.

But Carl never did get back in touch.

Sure, I got swept up with the reunion and all the reverberations from that damned Napalm Girl story stirred up by The Stringer documentary (scroll down through my earlier Substack posts, folks). Then came travel, decompressing, and eventually returning to Australia at the end of May. I wasn’t devastated—just upset. Disappointed at my old friend. I considered reaching out to Mika and letting her auto-translate carry my admittedly mixed feelings.

Then, ten days ago, I got a Facebook Messenger note from one of Carl’s former IVS colleagues from their Vietnam days, Gary—now back in the U.S. after years in Japan. He’d been forwarded an email from Carl’s older brother Ted’s widow, also Japanese, who had received a long-delayed message from Mika. What it said hit me hard.

She said Carl had sold his condo. She brought him close to where she lives and placed him in a care facility nearby. He’d been wandering. He needs care. I guess it’s Alzheimer’s. Poor Carl—but at least he’s safe and looked after. More anon, Gary.

A copy of Mika’s aunt’s original email arrived a few days later.

Alzheimer’s? I couldn’t believe it. But then I thought back to that day Koji and I visited him. Yes—there was something wrong. A distance. Like he wasn’t connecting. Off in his own world. Repeating stories. He never asked a thing about me, only spoke about himself. That steady eye contact, sure. But flat. Detached. The way he described getting catfished—as if it were just a grocery run gone wrong. No remorse. No regret. No emotion when we met, none when we said goodbye.

I asked my friend Koji—because that’s who he is now—to reach out directly to Mika. Just a couple of days ago, he forwarded her reply. Awkwardly translated, maybe even written that way. She apologised for not replying earlier and said, quite plainly:

“It would be difficult for my father to continue his relationship with his friend.”

Mika explained how Carl had become confused after selling the apartment and couldn’t decide where to go. Eventually, she brought him to Nara, near Kyoto—“almost kidnapped,” she said—because his paranoia and night-time wandering became so intense, she had to take a leave from work. He was certified in need of nursing care and admitted to a facility. No mobile phone. No outside contact.

“My father himself is not even aware that he is in a nursing home. His body is as healthy as ever.”

She ended with the stark diagnosis:

“The main reason for his illness is delirium and wandering due to dementia.”

And who knows what’s next for my dear and lifelong friend Carl? There seems to have been a reconciliation of sorts with his long-lost daughter. But can they even speak to each other? Her English is non-existent, his Japanese barely fluent. How do they communicate at all?

Proximity. Care. Survival.

Will she stay beside him—or simply let him go?

I think back to all those Kurosawa films we absorbed during our Hong Kong days, and the other Japanese noir flicks over the years. I can’t help but feel there’s a place for this story among them: a foreigner who came to Japan and lost his mind.

But knowing Carl as I do, I’m sure he’ll soon have all the other oldies chuckling away at his jokes. I also just hope that care facility in Nara has lots of room for his daily walks and keep that pedometer kicking over.

In Tribute to Carl A. Adams. Born, May 8, 1943. Sacramento, California, USA.

I’m very sorry to hear about your friend’s situation. Martin Dockery, in his book Vietnam: Full Circle, A Combat Veteran Returns, wrote about a European woman with dementia living in Vietnam with her European husband. When he died suddenly, she had no one to care for her, the police didn’t want to get involved, she wouldn’t cooperate with her embassy, and she ended up on the street, where local people and some kindly police fed her and did their best to care for her needs. I believe she ended up breaking a bone and ended up in a hospital, where she died from complications. (I could be mis-remembering the cause of her death.) She was living on the streets of Saigon for several months and it sounded truly harrowing. The situation in Japan is very different from that of Vietnam in the early 2000s, and I hope your friend can find the best care Japan has available for him.

Thank you for your care about Carl. We were involved in a teaching organization when he volunteered his university for an annual conference 2,000 strong. We had outgrown university sites by then. Even though Carl battled, we moved to commercial sites after that year. Everyone noted the toll it had taken on the organizating committee.

I'm still here, in a suburb of Tokyo, after 40 years and plan to die here. Thanks for the cautionary tale. If I can help, let me know.