No, it’s not fortune-telling. It’s something far older and wiser—the I Ching.

In The Bite of the Lotus: an intimate memoir of the Vietnam War, I recall a moment from late-1960s Saigon, when my friend - John Steinbeck IV, son of the famed American novelist - introduced me to Daoism. John had a strong spiritual streak and was deeply immersed in Eastern thought. He led me to the I Ching, or Book of Changes, a foundational text of Chinese philosophy that emerged from primordial shamanism, predating both Confucianism and Buddhism. Together, these three traditions - Daoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism - form the “Three Teachings” still followed by many Vietnamese today.

I’ve forgotten what we used for my throw - coins, yarrow stalks? - but John ended up creating a hexagram: six lines, some solid (Yang) , some broken (Yin). Each line represents a stage of change, and when certain patterns emerge - like three heads or tails in a coin toss - you get a second hexagram, showing where things might be headed. The lines themselves can shift, and their individual meanings often carry the sharpest insights.

How the I Ching Works (A Quick Primer)

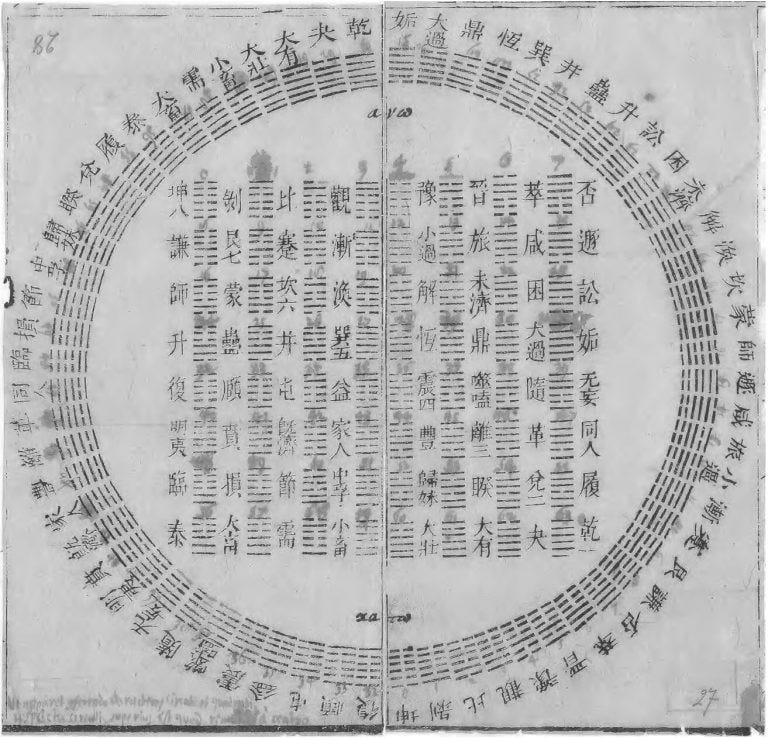

The Basics: The I Ching (Book of Changes) is built around 64 hexagrams - each a stack of six lines, either solid (Yang) or broken (Yin). These represent states of change and transformation.

The I Ching is built on eight elemental forces - called trigrams, or Bagua in Chinese - that represent natural energies and human archetypes: Heaven, Earth, Thunder, Wind, Water, Fire, Mountain, and Lake. Each hexagram is formed by stacking two of these trigrams, creating a symbolic interplay - like Thunder over Lake (The Marrying Maiden) or Water over Fire (The Abyss). These elemental pairings give each reading its distinct tone and texture.

I’ve got quite a collection of three coins from around the world to throw my I Ching, but these One Dong (piastre) coins from South Vietnam, or Việt Nam Cộng Hòa (Republic of Vietnam) and dated the year I first arrived there are my favourites. With inflation over the years, by war’s end in 1975 these wouldn’t buy anything.

Casting a Hexagram: You toss three coins six times to build your hexagram from the bottom up. Each toss gives you one line:

Two heads and one tail = solid line (Yang)

Two tails and one head = broken line (Yin)

Three of the same (all heads or all tails) = a changing line

Changing Lines: These are the wild cards. A changing line flips into its opposite - solid becomes broken, or vice versa - and can generate a second hexagram. That second figure hints at where things might be heading. So yeah—watch those lines.

Interpretation: Each hexagram has a general meaning, but the changing lines often carry the sharpest insight. They’re like footnotes from the universe—sometimes cryptic, sometimes startlingly precise.

On one stoned evening, John Steinbeck IV and I were gazing at a map and remarked how the shape of Vietnam perfectly embodied the classical Yin-Yang Symbol with the dots Cambodia’s Lake Tonle Sap and China’s Hainan Island. John later sketched it out while living on the Coconut Monk’s Island in the Mekong Delta. It’s called the Taijitu symbol and popularised in the Song Dynasty (960-1279) by philosopher Zhou Dunyi.

John Steinbeck IV read the cryptic result aloud from the thick book, and I sorta’ forgot about it. We also talked about Transcendental Meditation (TM) and his other spiritual discoveries. The most lasting of these was our - and especially his - connection with the Daoist Coconut Monk, who didn’t speak to anyone, lived inside a cement-rendered mountain overlooking a vast prayer circle of columned dragons, where wind chimes made from discarded artillery shells tinkled in the breeze. He was revered by his brown-robed followers, deserters from both sides of the Vietnam War.

But I had my heavy workload with the AP - as a photo editor, later a photographer and writer - and a growing family with my Vietnamese wife, Kim-Dung, to keep me busy. There wasn’t much time for spirituality. Sure, there was our Confucian wedding, and that boar-tooth Buddha pendant her family gave me to ward off the dangers of war. But I’d left behind the by-rote Christianity of my youth - the missionary and minister’s son burden - back in my first days at university.

I didn’t really visit temples - not with Buddhism so fraught in South Vietnamese politics. But the Yin and Yang of Daoism - that made sense. Male and Female. Light and Dark. Good and Bad. War and Peace. The Way.

And that Octagon. The Bāguà (Mandarin.) The Coconut Monk even designed an eight-sided table on his island for negotiators to end the Vietnam War, forget Paris! Just go with the flow, man. A survival technique, really. Just like c’est la vie. Que sera, sera. One more way to get through the damned war. And afterwards, a philosophy to handle the ups and downs of life.

And especially the down of my premature Mid-Life Crisis in the late ‘90s. And I was only 55! My best Vietnamese friend Lộc (whom you’ve met here before), saw the turmoil I was going through and suggested using the I Ching, as he once had. Three coins tossed six times. One side is Yin and the other Yang. Decide and be consistent.

First up? Hexagram 54 - The Marrying Maiden. Thunder over Lake. Yikes! Concubine in the household. Misfortune indicated. Get outa’ there.

And, well, I did - eventually. Along with many more throws of the I Ching, plus a Buddhist mantra Lộc gave me to recite twice a day.

My early props were pretty basic and soon disliked the rather harsh I Ching for Beginners bought at an airport shop.

From Lộc’s first introduction - with a simple fold-out cue card - I began building a small collection of interpretive books on the I Ching. My favourite remains Brian Browne Walker’s The I Ching or Book of Changes: A Guide to Life’s Turning Points. My copy (pictured above) is now well-worn and falling apart, with dates scribbled in the margins beside hexagrams.

And of the I Ching’s 64 hexagrams, I’ve called up every single one of them over the past twenty-something years, some uncannily frequently, others only once or twice. They’ve become familiar companions, each with its own tone and imagery.

The tome on the left is just plain hard work and rarely consulted, but I like the style of Sarah Dening’s with each reading sub-headed by an often well-known quote from a famous western writer, philosopher and scientist with a subheading on opportunities for personal growth. My second favourite book.

I have another book or two, but learned to stay consistent. Too many readings - especially online these days - can feel like you’re shopping around for the answer you want. Internet readings are fine, but be picky and don’t graze mindlessly.

But one thing I learned - especially in the thick of that turmoil all those years ago - is never to overdo the I Ching. It’ll just confuse you. You’ve got to choose your moment. Reflect. Meditate, even. Treat the I Ching with the 3,000 years of respect it deserves.

And never share your readings. Keep them to yourself. Sit with them. Let them work on you in silence. After a reading, I particularly enjoy reflecting on the eight element features of each hexagram and how they combine: like Heaven over Earth, Mountain over Lake, or even Water over Water which popped up after our recent heavy rains, images you can see and feel and remember.

It’s truly remarkable how often a reading lands with uncanny precision - capturing not just the moment, but your moment. And the advice? More often than not, it’s a quiet litany: relinquish ego, pride, impatience, anger, desire. Follow the teachings of the Sage. Or Lao Tzu, the founder of Daoism. Let go, and let the Way unfold.

These days, I might only consult the I Ching every couple of months - well-chosen moments like Tết, the Vietnamese New Year, or before another trip back to Vietnam, and perhaps again on my return. And lately, in times of great personal turmoil - especially from the backlash to the truth I’ve exposed about the authorship of the famous Napalm Girl photo in the controversial documentary ‘The Stringer’ (and no, it wasn’t AP’s Nick Ut) - the readings have been absolutely uncanny. And accurate.

So, breaking my own advice to keep your I Ching readings private - but in the hope of sparking your interest in this ancient tool of wisdom - allow me to share, by hexagram title, how this year has unfolded:

-Before Tết, back in Vietnam and ahead of The Stringer’s premiere at Sundance in January: Revolutionary Change and Creative Principle.

-Afterwards, back in Australia: Patience, Stagnation, and Retreat.

-Before returning for Vietnam’s 50th celebrations in April, knowing Nick Ut would also be there: The Cauldron.

-Back home in May: The Abyss and Limitation.

-And finally, on the 4th of July, after more personal attacks slumped me into near-depression, I knew it was time for an updated reading. What popped up? Turning Point.

Yay. Finally. Time to give everything a rest. But - as ever - watch those lines. “A wrong attitude prevents the return to light,” my favourite book warns. “It is time for careful self-examination and self-correction.”

And that’s why I junked that angry Substack I was writing - and did this much more pleasant one instead.

Thanks for the reading. It’s all in the flow.

The I Ching: A General Reading.

Originating in China over 3,000 years ago - possibly as far back as 1000 BCE - the I Ching, or Book of Changes, is one of the oldest spiritual texts in the world. Part oracle, part philosophy, it offers insight into the shifting patterns of life through a system of 64 hexagrams.

You toss three coins six times to build a hexagram: six lines stacked from bottom to top, either solid (Yang) or broken (Yin). Sometimes, certain lines are “changing,” which means they flip into their opposite and generate a second hexagram - pointing to where things might be headed.

The I Ching doesn’t give you answers. It gives you perspective. It speaks in metaphors - like The Cauldron, The Abyss, Turning Point, or The Marrying Maiden. And within those metaphors, it asks you to reflect, adjust, and align with the deeper flow of life.

As one modern interpreter puts it: “It’s not about what will happen. It’s about how to be.”