Vietnam 50th - Phnom Penh falls, and the rescue of a left-behind Cambodian staffer.

GRUMPY OLD VIETNAM HAND.

You might recall from my post a month ago (The South’s collapse begins) that I’d been over in Cambodia for weeks as the Khmer Rouge noose tightened around the isolated capital of Phnom Penh when North Vietnam ’s final offensive kicked off in mid-March 1975 against Ban Me Thuot in the southern Central Highlands and I rushed back to Saigon on a dramatic Air America chopper flight. Then, as one South Vietnamese city after the other fell on our side of the border, the situation over in Phnom Penh got even worse, but now with a strangely hopeful resignation that peace was returning to Cambodia.

Since the Paris Cease-Fire Agreement of 1973, the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong (officially the PRG, or Provisional Revolutionary Government) had a delegation in Saigon and one of my more surreal regular assignments was covering their weekly press conferences every Saturday out at cordoned off Camp Davis on the military side of Tan Son Nhut airport. (I could even call its French-speaking spokesman Captain Phuong Nam on the phone for media statements, or just passing the time of day. He features tellingly here later and I also caught up with him on our return 20 years after the war I 1995, now a dedicated capitalist seeking my help starting a laundry business.)

The Paris Cease-Fire Agreement provided for the positioning a delegation from North Vietnam and the PRG (Provisional Revolutionary Government, or VC) in Saigon who were locked up at Camp Davis on the military side of the airport but allowed to conduct weekly press conferences with the foreign & local media bussed in from downtown. Its spokesmen, led by Colonel Vo Dong Giang (second from left) and Captain Phuong Nam, spoke French and I was assigned to cover them, including phone contact, up until the Fall of Saigon in April 1975. (Years later in 1997, I met up with Giang - who later worked in Foreign Affairs - in Hanoi but wasn’t very personable, insisting all western journalists in South Vietnam worked for the CIA. Hmph!)

On Saturday, 12 April, I returned at midday from the weekly press conference out at Camp Davis – there’d been lots of glee over a number of spontaneous ‘popular uprisings’ – to hear that the Americans had pulled out of Phnom Penh.

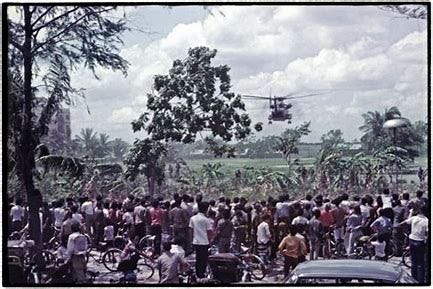

Giant US helicopters had swept into the surrounded Cambodian capital from aircraft carriers down in the Gulf of Siam, and taken out the ambassador and other embassy staff, along with a handful of journalists, including Denis Gray and Matt Franjola. Prime Minister Long Boret and Acting President Sirik Matak refused to leave, however, preferring to take their chances with the Khmer Rouge.

But somehow, our local reporter, Chhay Born Lay, and his family hadn’t made the evacuation.

Rushing out to Tan Son Nhut, our correspondent Richard Blystone talked a Continental Air Services DC-3 crew into flying to Phnom Penh and, alerted by Bureau Chief George Esper’s phone call to the AP office, Lay made his way out to a spookily deserted Pochentong for his rescue.

Sadly, in view of what was about to happen, they were the only passengers on the return flight. In Saigon, I embraced my Cambodian colleague, and invited him to stay with us for a couple of nights before he headed to the US as one of the first refugee migrants.

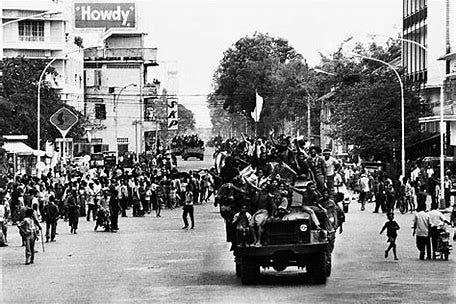

The fall of Phnom Penh to the Khmer Rouge took several more tension-filled days, and then there was absolute horror as the insurgents ordered everyone out of the refugee-swollen city, and into what would become Cambodia’s ‘killing fields’. There would be over 4 million deaths during the next four years.

Communication with the outside world was closed. Journalist colleagues who stayed behind tried turning Le Phnom Hotel into a Neutral Zone under the Red Cross but were soon ordered into the nearby French Embassy with all other remaining foreigners, including the Russians.

The Khmer Rouge then came and ordered out all Cambodians seeking refuge there, including Sirik Matak who was taken out and executed. It was another month before they were released and made their way overland to Thailand.

While I returned to Vietnam 20 years after the Fall of Saigon in 1995, it was many more years before I could return to Cambodia because of the pain I felt over what’d happened there.

With special thanks to Roland Neveu for his photographs.