Vietnam's 50th - Desperate hopes for a last-minute political solution.

GRUMPY OLD VIETNAM HAND.

Welcome back to Ho Chi Minh City - the old Saigon - after a quick dash up to Japan and where now I’ve joined the Vietnam Ministry of Foreign Affairs-sponsored “Press Week Commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the Liberation of the South and National Reunification Day of Vietnam.” So, no matter what they call it, we’re coming down to 50 years since the Fall of Saigon on Wednesday, 30th of April, and I’ve got to hand it to the Hanoi government’s firing up public enthusiasm like I’ve never seen before. On past major every five-year anniversaries, the last one 10 years ago, it’s just a cordoned-off parade past along a broad boulevard where the American Embassy was located, behind the Saigon Cathedral and towards the former Presidential Palace. Huge crowds dressed in red with gold stars have watched been practice marching for weeks with fireworks & drone displays, open air concerts and flypasts by Russian-made fighters and helicopter. Clearly, the government has tapped into the nationalist sentiment usually reserved for winning soccer matches against rivals like Thailand!

And so, catching up on excerpts from The Bite of the Lotus: an intimate memoir of the Vietnam War, we are now coming down to those last two tension-filled and dramatic days before the Fall of Saigon - and that chopper outa’ Saigon - which actually open my memoir. So, this short excerpt is the end of my book - with an Epilogue to follow.

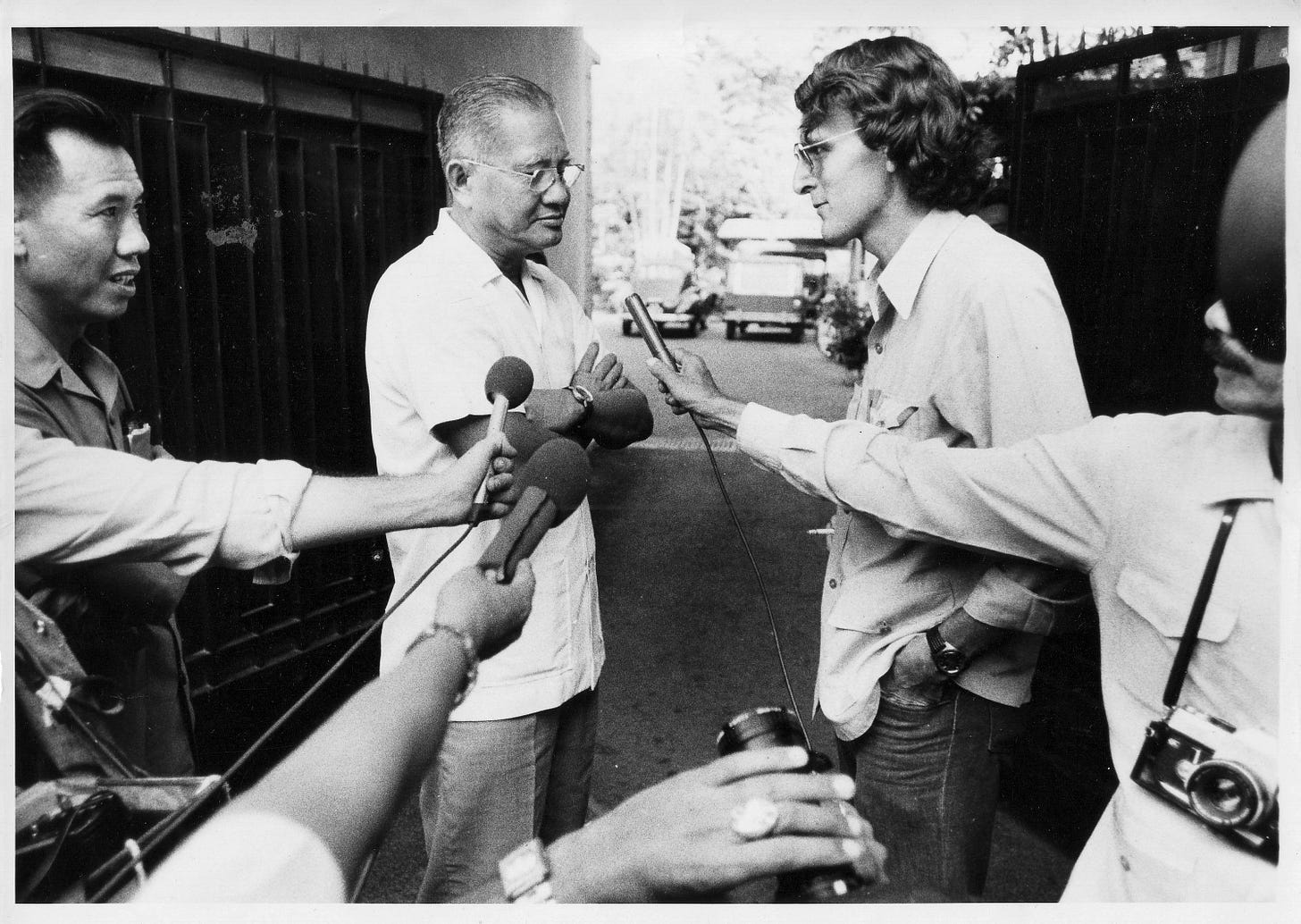

Enigmatic as ever, former General Duong Van (Big) Minh, wasn’t giving anything away as South Vietnamese politicians squabbled among themselves over a successor to resigned President Nguyen Van Thieu.

With the North Vietnamese virtually at the gates of Saigon, an unreal calm descended over the city. South Vietnamese President Thieu was gone, and rumours circulated of a political deal to bring in Third Force leader and ex-general Duong Van Minh, or Big Minh, to negotiate a real ceasefire and form a new government.

After slagging off Thieu as an American lackey for years, the Communists hinted that the leader of that November 1963 coup against President Ngo Dinh Diem might be acceptable. The French, ever wary of their remaining economic interests in South Vietnam, were supposedly brokering a deal.

My Third Force friend, the National Assembly deputy Ly Qui Chung, assured me that negotiations were taking place, and excitedly told me that the exiled Ngo Cong Duc was in Bangkok and ready to return. ‘You must stay,’ he assured me confidently. ‘Everything is going to work out.’

But for several tense days, Tran Van Huong, who was now the acting president, wouldn’t move, stubbornly insisting that both houses of the National Assembly approve any change of government.

The North Vietnamese moved ever closer, attacking Bien Hoa and sending thousands more refugees fleeing towards the capital. With its large block of opposition deputies and many pro-government ones already escaped, the lower house voted a bill approving the change, and passed it to South Vietnam’s more conservative Senate.

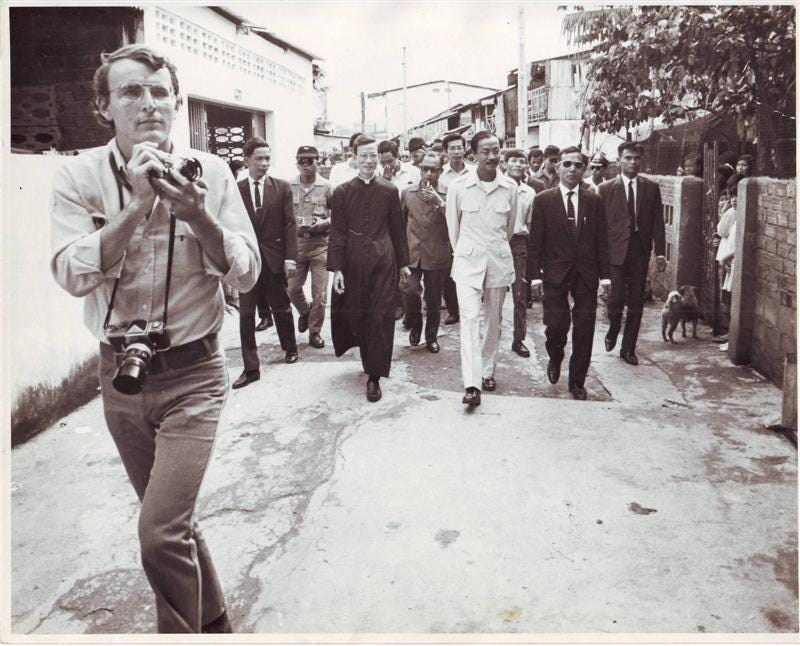

“Let’s turn Saigon into the next Stalingrad” former South Vietnamese Vice-President Nguyen Cao Ky during a visit to a shantytown out near the airport as thousands fled on a secret airlift. Flying his own chopper, he and his family would soon join the massive helicopter evacuation of the city on 29 April 1975 and its surrender the next day.

Arguing like a typical bunch of southern politicians, the senators talked through the Saturday. I popped out to a shanty town near Tan Son Nhut, where Nguyen Cao Ky, accompanied by a Catholic priest, was rallying folks to make a stand against the invading North Vietnamese. ‘Let’s turn Saigon into the next Stalingrad,’ Ky cried. In the near distance behind him, we could see USAF planes taking off with more secret escapees. The former VNAF air marshal, premier and South Vietnamese vice president publicly vowed to stay and fight. The Senate droned on.

Saigon was still untouched militarily. But overnight came a not-too-subtle reminder of what might happen, as the North Vietnamese fired a barrage of 122-mm rockets into the city’s southern edge, setting scores of tin-roofed shacks on fire and killing several residents.

Late on Sunday, the Senate finally named Big Minh as South Vietnam’s new president. The elusive former general and figurehead of the neutralist Third Force would be inaugurated the next day. At this stage of the game, I was hardly overjoyed that my gang was finally in power. But who knew? Perhaps both sides could work something out. A real ceasefire. Some sort of mixed government, as the Paris Agreement had envisaged.

Things were lonely at home with Kim-Dung and the kids gone. Dejectedly, I had my first hit of the day, checked my stash and headed to work. I called and congratulated my friend Chung, the new Minister for Information, and got details of the afternoon’s presidential inauguration – and instructions on getting into the Presidential Palace, never easy back in the dreadful Thieu days.

And then I headed home for lunch on 28 April 1975.