Vietnam's 50th - Evacuation Day as I run for those last choppers outa' Saigon.

GRUMPY OLD VIETNAM HAND.

Today’s the 29th of April - the 50th anniversary of the infamous US helicopter evacuation of Saigon back in 1975 - and the streets of today’s Ho Chi Minh City are packed with revellers for tomorrow’s huge celebrations of the end of the Vietnam War and the fall of South Vietnam. No one’s getting a night’s sleep. And the contrast could not be more complete to that panic-stricken day in which I was caught up way back then. Those enduring images of desperation, the most famous that Air America chopper on the roof by my friend & colleague Hugh Van Es. Others from the American Embassy.

So, please come along to the very last excerpt from the opening chapter of The Bite of the Lotus: an intimate memoir of the Vietnam War and my own helicopter flight out.

And from an unpublished draft, what happened when we landed on a US Navy ship out in the South China Sea on this very day back on 29th of April 1975.

Just after first light at 7 am of April 29th, I headed into work through eerily steamy yellowish light as the sun evaporated the previous afternoon’s rains. AP Bureau Chief George Esper had been up all night because of the attack on Tan Son Nhut; there had also been a ground attack on a satellite communication station on Saigon’s western outskirts. This enemy sure knew its ‘strategic targets’.

No one knew if the runways were damaged, but US ambassador Graham Martin was checking things out personally. One VNAF aircraft had already been blown out of the sky – apparently by a Strela, a heat-seeking, Soviet-made shoulder-launched rocket, or SAM-7. No fixed-wing aircraft were taking off, and the secret airlift had been halted. Was it time for the helicopter evacuation?

I became sulky and resentful when Esper asked me to type up a list of my contacts for a leftie woman freelancer he’d brought in to help on the political side. Why should I? I’d promised my Third Force friends, such as National Assembly opposition deputy Ly Qui Chung, that I was staying around. He was now the minister of information, and I couldn’t even reach him on the phone to say goodbye. And Father Chan Tin of the Anti-Corruption Movement, which had nearly brought down President Nguyen Van Thieu the year before. Now I was bugging out; I felt I was letting them all down.

About 9.30 am, Esper told us the evacuation was on and I should head home to get my things – just one bag each, plus a carry-on. Despite the curfew, more people were moving about in the streets. Father was still at home. I told him what was happening and headed upstairs to throw a few things in a large zippered bag. I pulled a couple favourite pictures of Kim-Dung from their frames and put them into my bag.

Back downstairs, I sat with Father, who was distraught. In the months before, when I was almost transferred to New York, we had formally adopted 13-year-old Phuong, the illegitimate daughter of her older sister, and we planned on taking her with us. In the chaos of that dreadful Operation Babylift, we’d even picked up travel documents for her. I’d never given her much thought or attention. She was just always there and part of the family. Another kid running around.

Now holding both his hands, I told Father I was leaving, and his eyes filled with tears. He’d already seen the departure of his favourite daughter – the woman who, at our marriage six years earlier, I had promised him I would never take away – and now I was going too. How had things come to this?

‘Please,’ he begged, ‘take my son – take Vinh with you.’

I choked back tears and nodded my head. ‘I’ll take Phuong too.’ I asked if he was afraid of what might happen next. Not very convincingly, he shook his head. We embraced goodbye.

Now that I was leaving, I reckoned, I might as well go out in style. I’d drive my old black Citroen, that classic car I’d never got around to shipping back to the US, out to the helicopters. But the damned thing wouldn’t start. So after patting Shep on the head, I hopped back on my motorbike, and – with Phuong perched on the back – headed to the office. There, I told Vinh he was coming too.

No ceremony attended my departure. I shook hands with George and Peter Arnett. Matt Franjola was out somewhere. Ed White and Neal Ulevich were coming later. With my two extra charges, I wanted to get a head start. I pulled the keys to my much-loved motorcycle from my pocket and tossed them to Huan, our top darkroom technician. ‘Keep it,’ I told him.

The last thing on my mind as I left were the three metal lockers in the Photo Department that contained the negatives of everything I’d shot for AP over the past seven years. Even today, just thinking of that lost archive still hurts.

We began walking to the evacuation point with my long-time friend Rick Merron, an AP photographer who’d been let go before the 1972 Offensive but had stuck around. Our evacuation point was over near the Grall Hospital, only about three blocks away, but we soon realised there was no way we were going to slip out of town unnoticed.

Small clusters of Vietnamese parked on motorbikes watched our every move. We were joined by other foreigners, mostly fellow journalists, as they left their downtown offices and hotels. Other bikes came and went. Talking, pointing and speeding off. They followed us to the evacuation point. The word was out: the Americans were leaving.

By now the streets were filling up. I wasn’t worried about the Communists, as they were still outside the city, but what if ordinary South Vietnamese turned on us? Or – worse – if disgruntled ARVN soldiers fired off a few rounds or tossed a grenade? I sure wouldn’t have blamed them for wanting to.

Given my own years-long bitterness towards American officialdom, I was embarrassed to be standing there in the hot midday sun as the size of our group continued to grow. After nearly two hours, a military bus pulled up – an old American school bus painted a US Navy grey, its windows covered by metal screens. Surprisingly, the driver was a white American. Everyone surged forward, and the bus filled in barely a couple minutes, with many standing in the aisle. Vinh, Phuong and I wedged ourselves into some seats at the back.

‘Stay here,’ the driver yelled to those left behind as we pulled away. ‘Another bus is coming.’ As we drove off into the increasingly busy streets of Saigon, followed by dozens of motorbikes, it was soon obvious not only that the poor bastard had never driven a bus before, but also that he didn’t know his way around. The blazing sun soon turned the inside of the bus into a simmering cauldron, and the two kids and I were sweating profusely. The Leica M5 around my neck was drenched.

At last we headed the right way – north, towards the airport – but tensions rose as we pulled up at the police and military checkpoint. Would they let this mixed bag of foreigners and Vietnamese through? No doubt the presence of an American driver was intended to make our entry easier. After several long minutes, we were waved through and left behind our outriders, the panic-faced Vietnamese on motorbikes who’d been following us.

As we looped around a driveway and headed towards the main entrance of Defence Attaché Office (formerly MACV, or Pentagon East,) I caught a glimpse of an Air America Huey chopper askew in what looked like a bomb crater, its main rotor flapping lazily around. There was no sign of any crew.

Then a single, loud explosion. Close and incoming. A 122-mm rocket, or perhaps even a long-range 130-mm artillery. The bus lurched to a stop and the driver fiddled with the opening mechanism for its single front door. Everyone wanted off the bus at once, and was standing and pushing with their bags. As panic gripped our mob, somebody yelled out, ‘Stop! Calm down! One at a time.’ It worked. The door opened. We disembarked and made our way into the DAO.

* * *

I hadn’t been inside the building for years – not since that bastard pacification czar Robert ‘Chainsaw’ Komer had tried to talk me into withdrawing my angry resignation from USAID after Tet ’68. The place was a typical US military establishment, with offices on the upper floors and the ground floor for amenities – cafeterias, a PX and even a barbershop.

We weren’t the first busload of escapees, and took our place along one side of the fluorescent-lit hallway. Thank goodness, the air conditioning was still working. I had no idea how long we would be here. I worried about the next explosion and if we’d be the target, but in the hallway everything was eerily quiet. We couldn’t hear any helicopters.

At one point, Dirck Halstead, a former UPI photographer now with Time magazine, walked back along the line and said to everyone, ‘I hope you’ve filed your tax return for the year. Someone from the IRS is checking people at the exit.’

I hadn’t filed a US tax return in years; for a frightening moment, I thought he was serious.

I was sitting with Anne Mariano, a tall and casually elegant American who’d built The Overseas Weekly into a semi-subversive thorn in the side of the wartime US military establishment. It was a popular publication with GIs. Anne was married to a handsome US Army chopper pilot turned ABC television reporter, Frank Mariano, who was off somewhere after covering Cambodia’s fall. They had adopted two Vietnamese girls; seeing Phuong, Anne offered to help with whatever was coming next. I thanked her.

Time passed, and finally there was movement at the far end of the hallway. People were leaving. A US officer came down the line, shouting that they were raising the number per chopper from 50 people to 65; everyone was now allowed just one carry-on. I rummaged through my bag, grabbed the pictures of Kim-Dung, dumped everything else and kept only my camera bag. We began to move down the hallway. In a blast of blinding light, the exit door opened ahead of us.

An officer counted us past and we ran out onto a baseball diamond coated in black diesel to keep down the dust. Lying flat on their stomachs in a wide circle around the field, fully armed Marines in flak jackets pointed their M-16’s outwards, ready to combat armed Vietnamese from any side.

Straight ahead, with its back ramp down, was a huge chopper – a US Marine CH-53 Sea Stallion. It was squat and heavy-looking, with two huge jet engines and a huge multi-prop rotor blade. The familiar, pungent smell of burning kerosene, now mixed with diesel and dust, assaulted our nostrils. The sky was a hazy white.

With Anne holding Phuong’s hand and me Vinh’s, we put our heads down and rushed to the chopper’s back door, up the ramp and into web seats not far down its left side. More people piled on behind us, filling the centre floor. The chopper throbbed to the sound of the engine. The props sharply changed pitch and – like popping a clutch – we soared sharply up into the air.

Out the open back door, I saw the entire panorama of Tan Son Nhut as we twisted away, its twin runways deserted and smoke rising here and there. A helmeted Marine crewman on my right was scanning the horizon even more keenly, his flare pistol at the ready. If any heat-seeking Strelas came after us, he’d try to distract them with blazing-hot flares.

Saigon soon disappeared off to our right, and we flew over the Rung Sat mangrove swamp. This was where a French ship had brought me to Vietnam as an idealistic young university student from Hong Kong in early February 1964. Up ahead on our right was the northern edge of the Mekong Delta. I knew exactly what was coming up next.

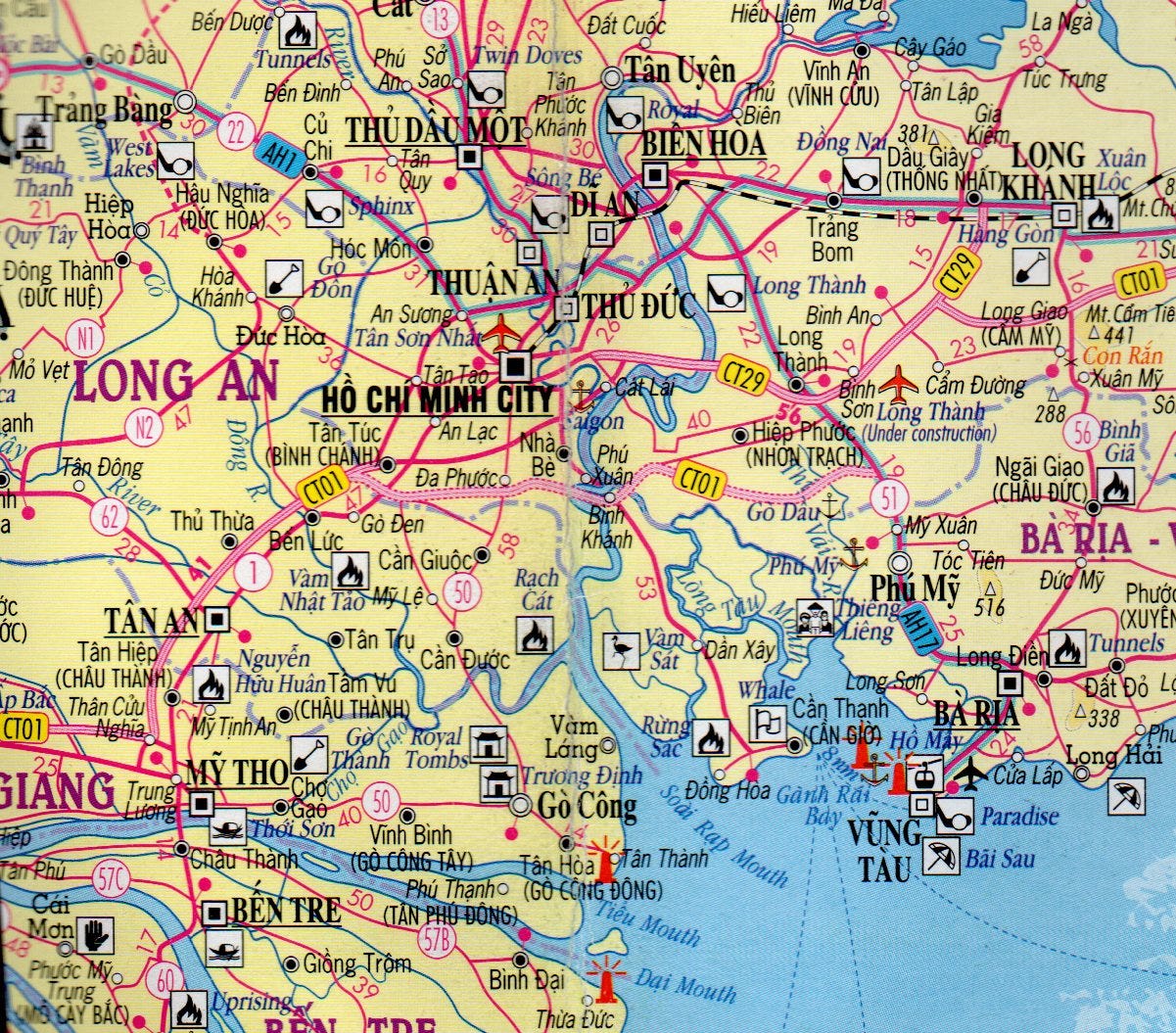

A modern-day map of Gò Công’s distinctive location at the mouths of the Saigon River, Vam Co and northern branch of the Mekong River, my Vietnamese homeland and where I was first stationed with USOM, later USAID, in mid-1964.

I stood up and, through the chopper’s rear window, saw Gò Công Province laid out like a map beneath us – the Saigon River, with the wide and winding Vàm Cỏ River forming its northern boundary and the straight northernmost branch of the Mekong to its south. This was my Vietnamese homeland. I spotted a couple clouds of smoke; probably just dry season fires, I thought.

I grabbed Vinh by the arm and pulled him over. ‘Gò Công!’ I yelled in his ear as I pointed. ‘That’s Gò Công!’

Other journalists jumped up, wondering what we were seeing.

‘Nothing for you bastards,’ I muttered to myself, waving them away. ‘This is private, family.’

On we flew, out over the South China Sea.

* * *

Barely a half-hour after lifting off from Saigon, the US Marine CH-53 Sea Stallion began its descent over the South China Sea. From inside the crowded helicopter, we couldn’t see a thing, just glimpses of grey sky and now dark seas out its rear window and cargo ramp. We shuddered to a stop on the small chopper pad at the stern of a US Navy ship and as we disembarked were waved along the railing by sailors to the main part of the vessel.

Clutching my large camera bag - all I had left after forced to abandon my bag of clothes at the last-minute – with Vinh and Phuong trailing along behind, I gazed out at the massive flotilla of over 50 ships, including a couple aircraft carriers stripped of their war planes, further out to sea.

Everywhere, I could see big choppers landing and taking off. And then in a deafening roar and whiff of burning jet fuel, ours took off for another run back up to Saigon and more evacuees. Under dark early rainy season skies, the air was full of the throbbing sounds of massive helicopters overhead.

We were on board the USS Mobile (LKA-115), an Attack Cargo Ship, at the top of the flotilla and closest to the South Vietnamese coast. Any landmarks, like those hills near Vung Tau southeast of Saigon, were no longer visible. On board our load of 65 were a handful of foreign journalists, none close acquaintances, but mostly Vietnamese civilians. But first up, we needed to be cleared and registered.

Wearing MP (Military Police) armbands, a detail of US Navy sailors ordered everyone to place their bags on the deck and open them for inspection. My camera bag easily passed but glancing behind me, I saw one of the MPs victoriously holding up a bottle of Johnnie Walker Black he’d found in a journalist’s bag. Okay, US Navy ships are “dry” – we all knew that.

But instead of just tossing it overboard, this officious fellow stood up, uncorked the bottle and slowly poured its contents into the South China Sea – and then the emptied bottle. The bastard! (And if there was ever a time when you really needed a drink, the Fall of Saigon certainly qualified as an exemption.) I couldn’t bear watching this sacrilege any further.

Now at the front of the line, another sailor seated at a table took down our names, organisation and age. Phuong was 15. But when Vinh was asked for his details, I was momentarily surprised when he replied 22. He’d been on those phoney ID papers for so long to avoid the draft that I thought him only 18 even though the family was lately worried he’d be called up for military service just as South Vietnam was collapsing.

I gave my details and was just about to leave when another sailor asked me to empty my pockets. Uh-oh. My last dwindling stash of heroin. I’m busted! Reaching down, I pulled out a pile of Kleenex fortuitously wrapped around that precious small plastic bag and - like a quick-fingered magician - shifted the lot into my other pocket. Phew! I’d need that.

We must’ve been the first helicopter onto the USS Mobile – or official one anyway. US Navy officers mentioned an earlier “unauthorised landing” by a VNAF, or South Vietnamese air force, UH-1D with five fleeing colonels on board which blocked the freighter’s only landing pad.

Fearing damage to the long antennas sticking out over the ship’s stern if they pushed the “Huey” straight overboard, the Americans ripped off one of its doors, handed the Vietnamese pilot a life-vest and ordered him to fly off the deck and jump out just before the chopper crashed into the sea. A waiting whaleboat would pick him up. (Worked well for a couple times apparently until one pilot almost broke his back and the USS Mobile, as on other ships, began shoving the renegade choppers straight overboard – and providing one of the most enduring images of the Evacuation.)

While Vinh and Phuong joined other Vietnamese in an assembly area below the chopper pad, I made my way into the main part of the ship where I was assigned a bunk way down below. With its own fleet of on-board landing craft, including tank-carriers, the USS Mobile was designed for combat assaults and normally carried a couple hundred US Marines.

But they weren’t aboard and their bunks – four on top of the other – were now available. And a guaranteed Claustrophobia Attack too, I thought, as I dropped my bag and headed back upstairs to the Ward Room.

I found Ann Mariano, the only foreign woman on board, was given the captain’s cabin with a separate lounge and couches that were much more inviting than those sardine-tight bunks below.

She’d tracked down that we could file stories over the Mobile’s communication system to the PAO (Public Affairs Office) aboard the nearby fleet command ship, the USS Blue Ridge, for relay to Clark Airbase in the Philippines and our AP representative there. Grabbing a spare typewriter, we quickly sat down and compared mental notes as I hacked a two-page colour piece on our last day in Saigon and our landing on the USS Mobile. My story noted that we had 200 Vietnamese on board and more than 35 foreigners.

My AP story from the USS Mobile after my helicopter evacuation included a ‘service message’ to advise Kim-Dung, evacuated earlier to Bangkok, of my departure and that her brother & niece were with me. Tragically, and some unknown reason, this dispatch and others were never received and my wife heard nothing about me for nearly one week.

Since that interrupted telephone call from the US Embassy in Vientiane, Laos, to the AP office in totally chaotic downtown Saigon only 24 hours before, Kim-Dung had no idea what’d happened to me – or her family. But my brother Richard would certainly have heard and told her the evacuation was on.

And so now at the end of my story, I included an urgent personal message for relay to Bangkok and then Vientiane for her that I’d evacuated safely along with Phuong and Vinh. “Will advise further as soon as can where heading,” my message read. “Meantime please stay Vientiane and will contact you through embassy and brother.”

Saving a carbon copy, we handed the story and messages over to the Mobile’s communications centre. I popped onto an outside deck just off the Ward Room, I found a private spot and lit up my Bastos Blue cigarette. Oh, shit. What a day. Tuesday, 29 April 1975.

What was going to happen now, I wondered? Even as we were running for the chopper out at Tan Son Nhut and then flying down the Saigon River and past Go Cong, I couldn’t – and wouldn’t - believe this was the end. Surely, after a week or so, I’d be able to return. Everything would be sweet except now the war would be over. Peace at last! And hadn’t the Communists promised a new era of national reconciliation and no recriminations? I wasn’t going to give up Vietnam that easily.

My plan – and desperate hope - was to stay in the region. I knew we’d end up in the Philippines. I’d get off there and then head to Bangkok and back into Vietnam once things quietened down. But then decisions started getting made for me. I popped back inside where Ann told me someone was looking for me by name. A US Navy officer. I quickly tracked him down and he broke the news.

“All Vietnamese nationals are being removed from the ship and transferred over there,” he said, pointing through the tropical dusk to a freighter a kilometre or so away. “The two who came with you are going too.” Well, I remonstrated, you can’t do that. They are my dependents and I am a US citizen. “No, they are Vietnamese and all Vietnamese are getting off the ship.” Again I objected, pointing out that we’d actually adopted Phuong whose documents now carried our name. “No, everybody’s off,” he gruffly replied. “And if you don’t like it, you can go with them.”

Well, where was the ship going? Where would the kids end up? The officer wasn’t sure. Guam, he reckoned, a good 1000 miles away on the other side of the Philippines. Or perhaps the US naval base at that country’s Subic Bay. Walking down below and thinking fast, I broke the news to Vinh and Phuong.

Ripping a double-page out of my journalist’s notebook, I carefully wrote out a “To Whom It May Concern” letter identifying them, their relationship to me and who I was. Colonel An, a South Vietnamese Army officer I knew from its press operations, promised to care for them and stick together. Figuring they’d be hanging around a few more days picking up other escapees, my plan was to sail on ahead and meet them and pull them off at Subic Bay.

Still, I felt terrible as they boarded one of the ship’s assault boats for the run across to the USS Sgt Andrew Miller, one of several contract freighters brought onto the scene to handle refugees as South Vietnam’s northern cities of Hue and Danang were falling to the North Vietnamese a couple months before. What’d happened on some of those ships was too horrible to even think about. And from what happened next, I’ve often wondered too how things would’ve gone if I had taken that US officer’s threat and joined them on board.

https://open.substack.com/pub/markmcinerney/p/april-30-a-memory-that-still-breathes?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=1b56qu

“Ed White and Neal Ulevich were coming later….”

Neil & his lovely wife Maureen were at our house in Bangkok for dinner the night my son,Philip (48 yrs old this past Sunday!) was born !!!