And here I am back in the former Saigon, today’s Ho Chi Minh City, in a downtown hotel on exactly the same day of 50 years ago, even close to the same time, when a rapid stream of personal and momentous events on 28 April 1975 just blocks away awoke me to the sudden reality that everything was finished. All hope gone. A feeling of total helplessness.

This is the painful and fateful day The Bite of the Lotus: an intimate memoir of the Vietnam War begins, the opening chapter of my story of 11 years in South Vietnam. You’ll recall my last excerpt, I was coming home for lunch.

It was 28 April 1975 and I was scheduled to cover the inauguration of Duong Van Minh – or Big Minh, as he was known – for the Associated Press at Saigon’s Presidential Palace at 3 pm, and I headed home for lunch. Pulling up outside our three-storey home in Saigon’s Tan Dinh district, I saw my Vietnamese father-in-law’s Citroen in the wide alleyway outside. After parking my motorbike just inside the gate, I walked into the living room.

He looked even more serious than usual. We shook hands and he pointed me to a rattan easy chair, taking another across from me under the high-ceilinged room’s huge fan, which was wafting lazily in the stifling heat.

I hadn’t seen or heard from my father-in-law, Phan Van Hoanh, since his daughter Kim-Dung and our children, Laura and Alexander, had evacuated to Bangkok the week before, as New York had ordered out all staff dependents. I would’ve been kicked out too if I hadn’t complied and forced my wife to leave her native country.

Sweeping all before it, the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) was now barely 30 kilometres outside South Vietnam’s capital. But as my father-in-law was a Third Force supporter, or neutralist, I assumed he would be staying on – just as I was – with hopes for a last-minute ceasefire, and even coalition government. War’s end, peace, national reconciliation and no recriminations, just like the Viet Cong promised.

But no – he’d changed his mind. ‘I want to go,’ he said. ‘Get me on that plane.’

Turning towards the kitchen at the back of the house, I looked for Kim-Dung’s mother, brothers and sisters. ‘Where is everybody?’

‘They’re still in Go Cong,’ Father replied. The family hometown was 60 kilometres south of Saigon, in the northern Mekong Delta.

Oh no, I thought. You came all the way up here and left them behind?

‘I can still get you out,’ I told him, ‘but I need them here now. Overnight!’

I rushed back to the AP office in downtown Saigon. Fighting had just broken out at the Newport Bridge, at the start of the Bien Hoa Highway on the north-east edge of the city, and looters were cleaning out the nearby American Post Exchange – known as the PX. My French photographer friend Michel Laurent had just been killed on Route 1, east of Saigon.

In a blistering tank-led offensive over the past six weeks, Communist forces had captured all South Vietnam north of Saigon, as its defenders fled in disarray. After raging off and on for more than 20 years, the bloody Vietnam War was reaching its final ignominious act.

I pulled AP bureau chief George Esper into his office and told him that my father-in-law now wanted out, but the family were still in Go Cong. Could I get them on that secret airlift for local staff of US news organisations wanting to escape?

‘Get them up here and we’ll get them out,’ he assured me.

With my gut aching from dread and depression, I made my way up to Big Minh’s presidential inauguration. Parking my motorbike outside a side gate, I presented my credentials and walked in bright sunlight with other journalists past lush, manicured lawns to a small entrance at the back of the palace. Access hadn’t been this easy when President Nguyen Van Thieu had been running the country; he’d resigned the previous week.

As we walked up the back stairs to the main hall, everything went dark as heavy clouds roiled over Saigon, a thunderclap struck and huge drops of rain began to fall. The rainy season was still a couple months away. What was going on? Over my dozen years in Vietnam, I had come to believe in signs, omens and symbols.

While we waited for the ceremony to begin, an aide walked up to the podium, removed the Republic of Vietnam’s presidential seal and replaced it with a five-petalled white flower on a pale blue background with a red and white yin-yang symbol at its centre. An emblem of Taoist wisdom?

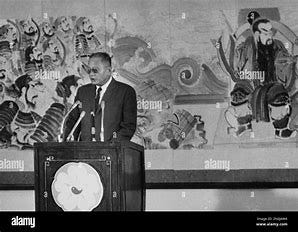

In a sombre voice, Big Minh, the stooped and bespectacled former southern general who’d led the US-backed coup against South Vietnam’s Ngo Dinh Diem regime a dozen years before, drearily read out his inaugural address.

Referring to the VC by its proper name, the Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam, he muttered pleadingly: ‘We sincerely want reconciliation. You know that. Reconciliation requires that each element of the nation respect the other’s right to live. That is the spirit of the Paris Agreement. Let us sit together and negotiate and work out a solution. I propose we stop all aggression against each other. I hope you will approve my suggestion.’

In closing, he mentioned the secret airlift by which thousands of South Vietnamese had already fled, and which my wife’s family now wanted to join. Big Minh begged for people to stay. ‘Please be courageous and stay here and accept the fate of God.’

So much for my Third Force hero.

Under gloomy skies, I returned to my office and hacked out the story. Kim-Dung’s father and a family friend, Kim, were in the office visiting her younger brother Vinh, who I’d got a job for in the darkroom after other Vietnamese staffers fled to the United States.

Esper wanted comment from the VC delegation out at Camp Davis, a sealed-off compound on the military side of Tan Son Nhut airport. I was reaching for the phone when explosions rumbled and shook the entire building. It sounded like it was coming from the airport about five kilometres away. Then the bangs were right outside, as heavy anti-aircraft fire broke out from the Presidential Palace. Looking out Esper’s office window, I saw a low-flying South Vietnamese Air Force C-130 dodging and weaving over downtown, tracer rounds following it across the rain-darkened sky.

In the rain-splattered square below, people ran in all directions. Father was under a desk in the office and Kim squeezed behind a metal cupboard, her eyes wide in fear and screaming.

Just then, the AP’s Tiger Line – our US military phone – rang. My younger brother Richard (Muk) was calling from the American Embassy in Vientiane, Laos, where a worried Kim-Dung and the kids had flown from Bangkok. I crawled under a desk in the Photo Department, covered one ear and told her what had happened.

Her father was here but the family were still in Go Cong. Perhaps tomorrow or the next day we’d get them out. When I passed the phone to her dad, the Vietnamese operator cut off the line, saying their call wasn’t important.

Details quickly emerged from eyewitnesses of five VNAF twin-engine A-37’s screaming in from NVA-captured airfields in the east to bomb and strafe the vast facility. Another bunch of defectors to the other side; so much for Big Minh’s ceasefire proposal.

Finally, I picked up the phone and dialled VC spokesman Major Phuong Nam out at Camp Davis on the Tan Son Nhut airbase, with whom I’d developed quite an easy-going relationship over the past couple of years. Speaking French, I asked about the bombing and if he and the others were okay. No doubt they had been warned and were hiding six feet underground.

‘It was close,’ he told me coolly, ‘but we’re all fine.’

I told Phuong Nam that I’d just covered Big Minh’s inauguration, and wondered if the delegation had any comment. ‘Yes,’ he replied – somewhat surprisingly to me – and rattled off a three-paragraph statement with hard-line demands I’d never heard before. The most significant was ‘an end to the Saigon administration, a tool of American neo-colonialism, and an end to the machinery of war and oppression against the people of South Vietnam’.

‘So you’ve got nothing to say about Big Minh’s call for a ceasefire and negotiations?’ I asked.

‘No.’

‘Well, au revoir, then,’ I said, and hung up. I felt drained.

‘What did he say, Carl?’ Esper asked urgently.

All I could do was shake my head and fight back angry tears. The bastards, I thought. It’s over.

* * *

After the air strike on the airport, the Big Minh government imposed a 24-hour curfew and sent troops out into the streets of Saigon. Official Americans were given 24 hours to leave South Vietnam.

As we wrapped up our stories for the day, the long-anticipated helicopter evacuation of Saigon looked like happening any time. Esper pulled me aside and said he and New York had decided that I was one of the AP staffers who would leave. Only he, Peter Arnett and Matt Franjola were remaining. I nodded numbly and headed home.

We’d known of US plans for a helicopter evacuation for some time, and had seen one over in Phnom Penh just a couple weeks earlier. As possible participants, however, the Saigon Press Corps was sworn to secrecy. Upon hearing Bing Crosby singing ‘White Christmas’ on the local US Armed Forces Radio station, we’d tiptoe to designated evacuation points around town, board buses to Tan Son Nhut and fly away on helicopters. That was the plan, anyway.

Esper’s order stung me. I had always assumed I would stay in Saigon. I knew the players and wasn’t particularly worried about a Communist takeover. I’d been in South Vietnam since 1964, and – as I saw it – had bloody well earned the right to stay. I wanted to witness the end of this stupid Greek tragedy. But with Kim-Dung’s family now desperate to leave, I was hardly able to make an issue of it. The decision was made for me. My Confucian duty called.

I often joked that I hadn’t married only her six years before, but her entire family – even the whole province.

Perhaps we’ve still got another two or three days, I thought as I drove home through tense, deserted streets. Why hadn’t Father brought everyone up with him today? Why was he in the AP office this afternoon when all hell broke loose and not hot-tailing it back down to Go Cong to pick up the family? The airport attack hadn’t damaged the runways and the secret airlift was continuing – we knew that much.

Our cook laid out a late dinner for me on the dining room table, a simple Vietnamese meal of fried fish, pork ribs and leafy green soup with steamed rice. No one else was awake and I gazed out into the living room. That familiar rattan furniture from our very first love nest seven years ago in another part of town . . . The colourful Cambodian reed mats from that motorbike dope run down to Chau Doc with Sean Flynn . . . The cabinet with my stereo system, my years-long collection of records and cassettes . . . So many books . . . A catch-all basket with my draft card, that flimsy last will and testament from my friend Sean Flynn, who later disappeared in eastern Cambodia . . . Bits of stoned poetry and knick-knacks from over the years.

In the middle of the room were packed boxes addressed to my folks back in Denver, a favour for photographer Phuoc, who’d brought his valuables around and even packed up a few of my pictures and diaries before escaping on the secret airlift with his wife, Hoa, and two kids. He’d shipped out several boxes through the US military’s mail system, and I’d promised to ship the rest but hadn’t yet found time. Shep, the German shepherd we’d brought back from a Bangkok R&R a couple years before, was asleep out at the front gate.

I wasn’t particularly melancholy or contemplative, just exhausted, brain-dead and in need of a last-minute hit before going to bed. My stash of heroin was getting low; I’d need to make a top-up run tomorrow. Sleep came quickly.

About 2 am I was awakened by the rumble of multiple explosions as Tan Son Nhut came under a sustained rocket attack, punctuated by occasional single ground-shaking blasts. I tossed around on my waterbed until the sounds quietened down and I fell back to sleep.