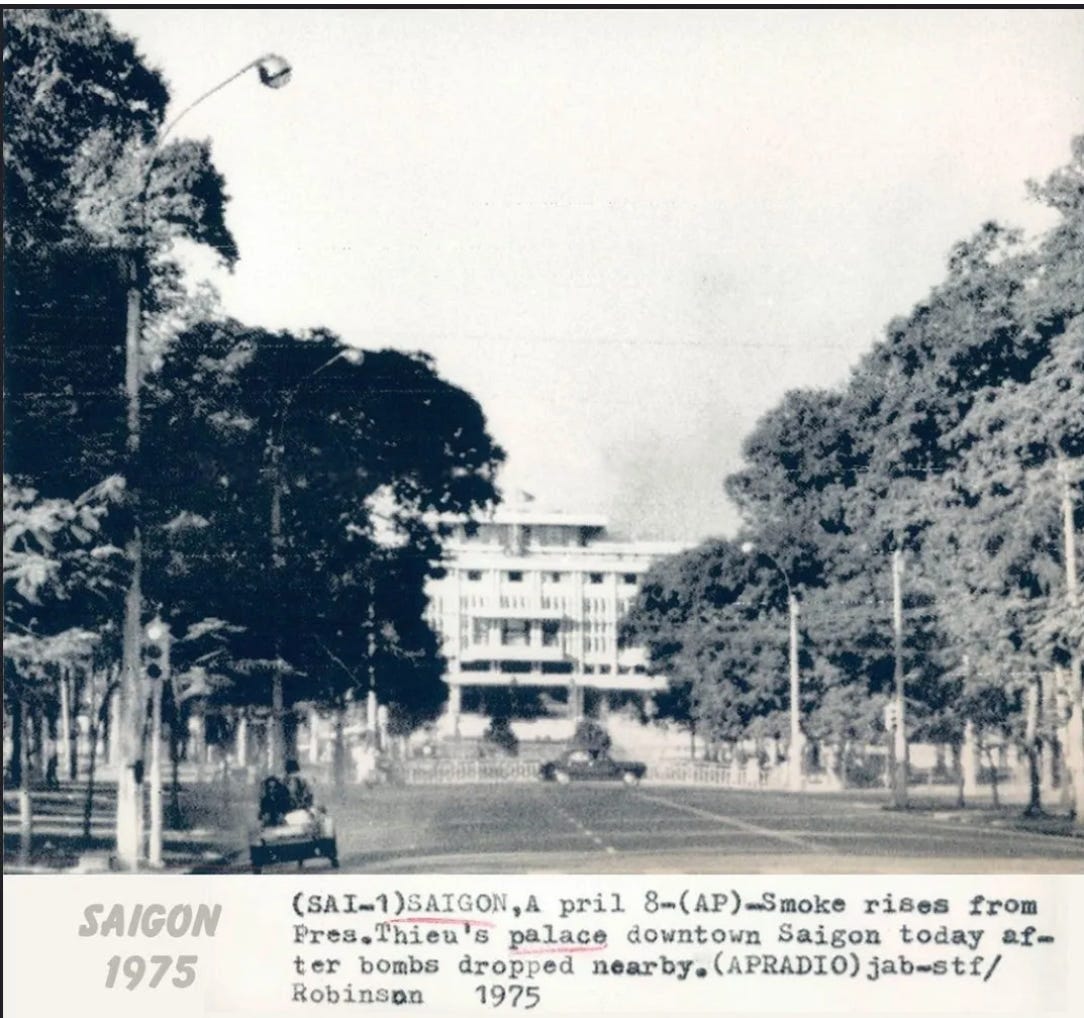

Another significant event - now in the first week of April 1975 - leading to the Fall of South Vietnam was the bombing of Saigon’s Presidential Palace by a VC agent pilot with VNAF, the country’s air force and, long led by northern refugee Nguyen Cao Ky, was long considered the most staunchly loyal to the Saigon regime. And now with thanks to Kat Fitzpatrick Stories of Vietnam for finding the original (as sent out) AP radiophoto of that day’s surprise attack, I’ll pop back my own memories of the 8th of April and a bit more with this short excerpt from The Bite of the Lotus: an intimate memoir of the Vietnam War. (Thank you, CIA kid Kat!)

As MACV’s last two commanders, generals Frederick Weyand and Creighton Abrams, completed a week-long inspection one month into the Offensive, the North Vietnamese paused in semi-desert country just north of Phan Rang, 350 kilometres north-east of Saigon. Back in Washington, the pair told Congress that South Vietnam could not survive without additional aid, and Ford asked for $722 million in emergency military help, plus $250 million in economic and humanitarian aid. Over the past month, Thieu had lost the entire northern part of the country. Could he hold this new line?

Life in Saigon continued in odd normality. The kids were up early and off to preschool before the rush hour, and me to work on the motorbike. For years, all aircraft except President Nguyen Van Thieu’s personal helicopter were banned over downtown Saigon as a coup-prevention measure. One morning about 7.30 am, with just Ed White and me around, I was just wrapping up a dump and smoking my first hit of the day in the office toilet when I heard an aircraft flying low over the city.

I dashed out, ran over to the bureau chief’s office and threw open the window, spotting a sleek VNAF F-5E diving down on the Presidential Palace, only three blocks away, and then heard a thunderous explosion. In the odd silence that followed, I heard the plane heading north at full speed.

As I yelled out what I’d seen, Ed began typing out AP’s first bulletin, but we were uncertain if the attack was the prelude to a military coup or just a disgruntled pilot. Arriving for work, me and our Vietnamese photographers and reporters rushed out. But the smoke had already cleared, and no damage was visible from the streets outside, which were now crowded with curious onlookers.

Soon Kim-Dung was on the phone from home. The kids were fine. Their school was just on the other side of the Palace, and Alexander, not even four years old, was the first kid under the desk when the bomb went off. Laura was okay too; the maid brought them home. We were proud of our son’s instinctive reaction, but both children would frighten quickly at any sudden sounds for years afterwards.

It turned out a coup wasn’t underway – but something much more ominous was. Trained in the US on the entire range of VNAF aircraft, the F-5 pilot was a Communist agent, and he flew on to a hero’s landing somewhere north of Saigon.

Led by the staunch anti-communist and northern refugee Nguyen Cao Ky, later premier and then vice president, and who still commanded fierce loyalty within the ranks, the VNAF was made up of true elites. Who else was out there ready to turn the tables? In the post-war years, the former VNAF lieutenant Nguyen Thanh Trung would become vice president and chief pilot of the state-owned Vietnam Airlines.

[He was also the first Vietnamese to pilot the Boeing 767 and 777 for Vietnam Airlines out of Seattle, Washington. He’s still alive, now 77, and I’d really love to meet him! See his story on how he joined VC after his father was tortured and killed by South Vietnamese troops, Wikipedia.]

Although the strike had caused hardly any damage to the palace, the psychological effect was substantial. Saigon was already filling with broken and hungry soldiers and refugees from the fallen northern provinces. With news strictly controlled, rumours took over. The mood was becoming menacing.

One afternoon, I was riding back to work through crowded post-siesta traffic and noticed an unfamiliar licence plate on another bike – DN for Danang – and I gestured in a friendly manner to its driver, a South Vietnamese Navy enlisted man.

Before I knew it, he cut me off from the left and, speaking Vietnamese, asked for money. I never carried much, but when I hesitated, he lifted up his shirt and put his hand on the .38 Smith & Wesson revolver tucked into his belt and nodded menacingly. I handed over what I had and he took off. No one even seemed to notice.

I was so shaken by the incident – and by my stupidity in nodding hello to the bastard in the first place – that I didn’t tell anyone in the office or at home about it. I called up my old friend Paul Vogle, a Vietnamese-speaking correspondent at UPI, who suggested I write a story about it. But I couldn’t. And I wondered: what would happen if these folks suddenly turned their guns against us? Were we the enemy now?

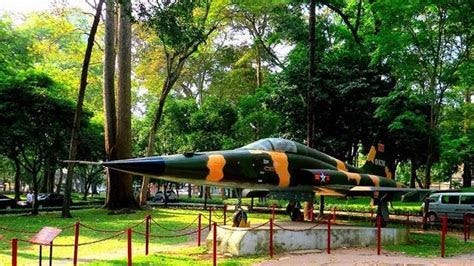

A former VNAF, or South Vietnamese Air Force, Northrop F-5E Tiger II, also known as Freedom Fighter, outside today’s Reunification Palace in Ho Chi Minh City, formerly Saigon. I’d be surprised if this was the original which ended up at a diret airstrip at Loc Ninh 100 kms north of Saigon near the Cambodian Border. This was VNAF’s most advanced bomber and no match for North Vietnam’s Soviet-built MIG-21s.

The most important event of April 8 was not the bombing of the Palace but the arrival of the latest dispatch from the most important spy of the war, a double agent operating for the CIA and the National Police inside COSVN, the top Communist command for the Saigon area and the delta Having stolen every key COSVN secret since 1965, Vo Van Ba outdid himself this time, giving us the outline of Hanoi's plan for winning the war. He told us that the Communists intended to launch immediate attacks in and around Saigon, with a view to seizing it at the first available opportunity, and, most importantly that all rumors of negotiatiated settlement being spread by the communists and their diplomatic dupes were part of a ruse to keep us all off balance. Within hours CIA director Colby briefed Ford and Kissinger on the report. On its face it dispelled all doubt that the communists might wait until after the of start the rainy season to move against the capital and that they might forego such a push altogether in favor of a political bargain. That meant im turn that Ambassador Martin should stop dragging his feet and begin accelerating the drawdown of surplus embassy personnel and preparing earnestly for an emergency evacuation. But Martin and my own boss CIA Station chief Tom Polgar remained mesmerized by their own wishful thinking and false signals from the French embassy and the Hungarian ICCS delegation in Saigon that negotiations were possible. And Kissinger became increasingly infatuated with the idea that the Soviets could be induced by their own interests to intervene against Hanoi. So the air went out of the evacuation balloon, and related planning contiued to languish. A week later the French convinced Polgar that Theiu's removal would jump start negotiations. Martin reluctantly bought into this and Kissinger kept all of us in supension as he waited for the Soviets to reply to an appeal for help that he had filed through Ambassador Dobrynin in Washington. Terrified that evacuation planning would remain in second gear I met directly with Vo Van Ba on April 17 and received the latest on Hanoi's game plan. He discounted the importance of Thieu's proposed departure and the chances it might kickstart negotiations, pinpointed the kickoff date for Hanoi's attack on Saigon and predicted NVA airstrikes on Tan Son Nhut airbase. Did this finally change anybody's mind? Stay tuned.