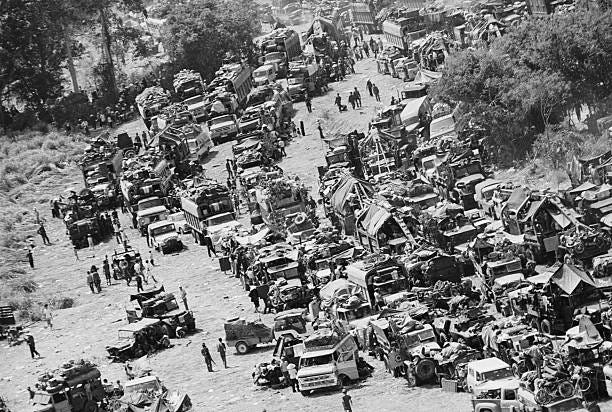

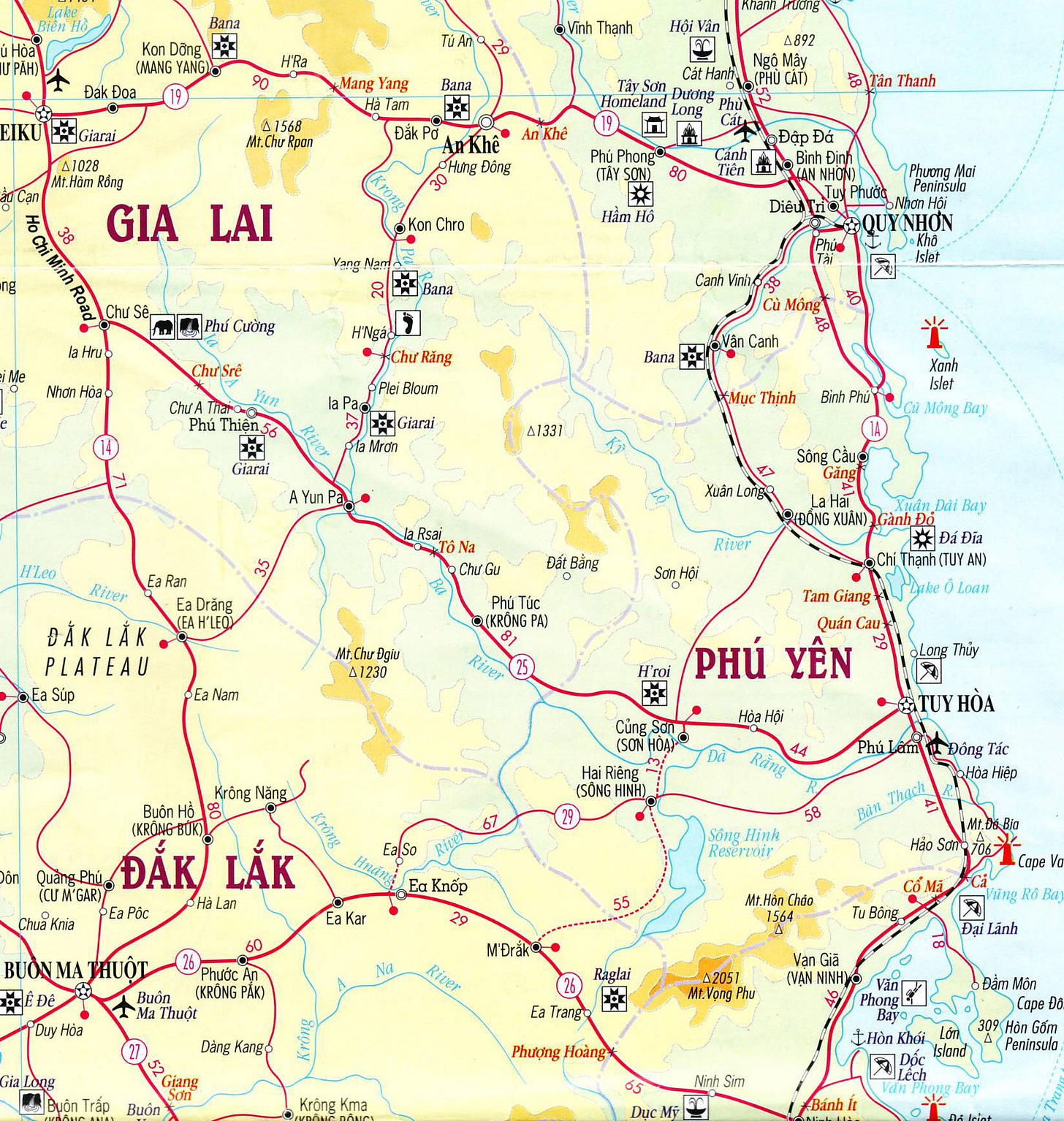

Also known as the ‘Convoy of Tears,’ the panicked flight of hundreds of thousands of South Vietnamese military and civilians from the Central Highlands down a little-used road to the coast after the decisive the Battle of Ban Me Thuot in early March 1975 was truly one of the worst slaughters of the Vietnam War. (See my last post.) Back in early 2011, I made my own personal pilgrimage by motorcycle down Route 7 - today’s Route 25 - with a couple Vietnamese friends and later posted this story on my Google Group of those who covered the war, ‘Vietnam Old Hacks.’

Our eight-day trip began in Saigon and up Cambodian border through Gia Nghia and around BMT to northermost point of Pleiku, then coastal Tuy Hoa, Nha Trang, up to Da Lat and down to Bao Loc and back into the city. I was on a Taiwan-made Bonus 125cc motorcyle, a reverse-engineered copy of the classic Honda 125cc.

Surely one of the most gut-wrenching episodes of the collapse of South

Vietnam back in 1975 was the sudden withdrawal of its troops from the

Central Highlands shortly after the fall of Ban Me Thuot. Only two days

after that city fell and citing the lack of military reserves, President

Nguyen Van Thieu ordered the evacuation of the entire highlands -- and northern I Corps as well. In a strategy dubbed "light at the top and heavy at the bottom," the final stand against the North Vietnamese would take place around Saigon and the Mekong Delta. Thieu's shocking and precipitous decision, quite simply, sealed and accelerated his own fate -- and that of South Vietnam. The panic was on.

The decision to abandon the Central Highlands was top-secret and certainly

wasn't announced at the 5 O'clock Follies, or what passed for them in Saigon

during that post-cease fire period. I can't recall now how soon we at AP,

and others for that matter, got onto the story.

Everything was happening so quickly and Saigon was still talking about a counter-attack on Ban Me Thuot. But soon the story emerged that a huge column of South Vietnamese troops and officials, their families and other civilians, was making its way

out of Pleiku and Kontum down an unknown and little used road to the coast

at Tuy Hoa. We sent a correspondent and photographer - I forgot exactly

who -- to Tuy Hoa to meet them.

And as the first of the column arrived, a totally horrific story of ambush and massacre emerged. Wheeling (literally) out of BMT just over 100 kms to the southwest, the NVA had brought the entire column under devastating artillery, armour and ground

attack. Unknown thousands of these South Vietnamese were killed, wounded

or left behind. Anyone who survived and reached Tuy Hoa was damned

fortunate. But they were also damned to fall soon enough into NVA hands.

Way in the north, Quang Tri was gone and Hue was falling as the survivors

staggered into Tuy Hoa. The NVA's famous 320A Division who'd chased them

down that road were right behind them.

Those survivor stories -- and my own mental images -- from that deadly

withdrawal from the Central Highlands in March 1975 have stayed with me for

years. Every time I've passed through the lovely provincial capital of Tuy

Hoa along Vietnam's Central Coast, 200 kms north of Nha Trang, I've gazed

inland up its wide river valley into the distant highlands and those

nightmarish images return of what it must've been like for those people.

I'd done Route 19 from Pleiku down through the Mang Yang and An Khe Passes to Qui Nhon with its own dramatic history of the ambush and decimation of France's Groupe Mobile back in 1954 in the First Indo-China War. But I'd always wanted to see and experience what's now known as Route 25. My friend and fellow bike-rider Trang said the run wasn't nearly as spectacular as Route 19 and was also in pretty bad shape, or at least the last time he'd driven it. That was his biggest concern -- just how long the trip would take. But we went ahead and put the road for Day 5 (a Monday) on our itinerary -- and I was looking forward to finally making this journey of remembrance.

Journey’s end at Tuy Hoa with my friend Trang at right, fellow traveller Huong centre.

Over the years, I've seen few references to what happened along Route 25

back in March 1975. At some stage after we returned to Vietnam in 1995, I

read NVA General Van Tien Dung's Our Great Spring Victory and his version

of what happened -- how Saigon's sudden abandonment of the Highlands had

surprised Hanoi's high command and how totally annoyed he was with his own

commanders for under-estimating the possibility of the South Vietnamese

retreating along what was then known as Route 7A. (In fact, they'd assured

him twice that the road was unusable.)

"If the enemy escape, it will be a big crime," he reprimanded the commander of the NVA's 320th Division, "and you will bear full responsibility for it." And in the military imperative of those still early days of their final offensive against Saigon, the NVA

certainly needed to ensure that these South Vietnamese would never regroup

and fight again. But that reading about the episode was some time back

and had gone a bit fuzzy.

It was only after I'd actually made the day-long run from Pleiku to Tuy Hoa

-- and certainly a highlight of our trip -- and returned home to Australia

that I discovered much more has indeed been written on this still

little-known episode of the Vietnam War.

Thanks to Google, I found several valuable references about what happened along Route 7B, including a "Google Translation" from the memoirs of an ARVN Ranger who'd survived. As an old journalist, I should perhaps have done my research beforehand. But then my trip would've had a totally different feel. Besides, who amongst us has not had a similar experience where all the pieces only fall into place after you've seen them?

I guess this must happen all the time at our age when things don't make sense until afterwards. And so, rather than come across as some post-facto battlefield "expert," I'll play this one straight -- and then fill in the blanks from what I discovered later.

The morning in Pleiku -- elevation 800 metres -- was amazingly chilly. [This was February 2011.] Rather than go for a walk, I choked and fired up the motorcycle to explore around a town now grown to over 115,000 inhabitants. Like many of today's

provincial capitals, Pleiku is an attractive place with wide boulevards and

parks, both nicely landscaped, with many new buildings, some multi-storey

office and apartment blocks and hotels, spreading out over the hilly landscape.

It was just past 0600 and traffic was light but many children, all bundled up in sweaters and jackets, were making their way on foot or wheels to the first school shift of the day. A six-lane boulevard heads north towards Kontum, less than 50 km away, and is lined with neat homes and shops. Coming down the slope out of town, I almost missed the right turn into Pleiku Airport. They've got a nice civilian terminal and I

could still see remnants of what was once the American military's Camp Holloway. I then explored around the town past the old provincial headquarters, now refurbished, and other government buildings and into the business district.

We were soon back on Route 14 and back-tracking those 38 km south through

rubber plantations to Chu Se, formerly My Thanh, and the junction with Route

25 where we now turned south-easterly towards Tuy Hoa, 180 kms away.

I was re-living the journey of that fleeing column of South Vietnamese all those years ago and alert to everything around me. For one thing, the escape from Pleiku would've taken place about the same time of year, but roughly one month later, and the overall appearance and weather about the same, still cool with high cloudiness. The pepper plantations for which Chu Se is now famous disappeared behind us as we descended gently on a wide ridge off the Pleiku Plateau, clearly a watershed between the Mekong River and Eastern, or South China, Sea. To the right was that wide savannah-covered catchment we'd crossed the day before with the Dak Lak Plateau and distant mountain ranges behind and its waters flowing into Cambodia and the Mekong. Off to

the left were other ranges inland from Qui Nhon and a man-made lake, and its waters heading east. Traffic was light and the road in good condition.

The population was heavily Montagnard, Giarai in this case, and the

landscape quite dry with crops of manioc, a few patches of cotton and the

occasional flowering tree, or bong hoa, as Trang called it. We stopped for

a closer look at its huge blossoms which reminded me of the African Tulip

tree. And then, rather quickly came a shallow pass -- Deo Chu Sre -- in a

rugged sparsely-vegetated landscape of huge granite boulders and dramatic

escarpments. Soon, we were down in a lush green rice-growing valley fed by

canals off that dam we'd seen off in the distance. We stopped for coffee

next to a river which flows into the Ba River, a major tributary of the Da

Rang which ends at Tuy Hoa. (The advance units of that column would've felt

it was all downhill from here.)

Ever since we'd left Chu Se, the "kilometre-borne" indicators had -- among

other places -- noted the distance to a locality named Ayunpa which was both

unusual and unfamiliar. (Only later would I discover this was formerly

Cheo Reo, the capital of war-time Phu Bon Province which lay in the middle

of the southern part of the Highlands surrounded by Phu Yen, Dac Lac, Pleiku

and Binh Dinh provinces.) After our break, the valley -- planted heavily

in rice -- continued to widen as we headed south past a string of Gialai

villages, the long-houses on stilts. But there were also a lot of

Vietnamese, especially in the small towns, who lived alongside them.

Closer to the town, the rice fields switched over to sugar cane and, with

the harvest in full swing, we passed by a huge convoy of trucks outside a

sugar mill on the northern side of town. There wasn't much to the town

beyond a tight government and business district. But I did notice where

the link road to Route 14 and Ea Drang where we'd had lunch yesterday --

only 35 kms away -- and then BMT another 80 km to the southwest.

Once the NVA heard the South Vietnamese were escaping down Route 7A and passing through this valley, the NVA would've sent every spare unit, tank and artillery piece in hot pursuit -- and this is where they met up. Right here.

The run from Pleiku and Chu Se had been much smoother than Trang

anticipated. But now -- quite symbolically, I thought -- the road

deteriorated badly. Just east of the town, the river tightens into a gorge

with the road hugging its right bank below steeply-rising hills. We were

entering another pass -- Deo To Na -- and I could immediately sense another

"choke point" for that fleeing column. Classic Ambush Country. The South

Vietnamese would've been torn up here for sure.

And finally after only a couple more kilometres, we were out the other side onto a river flatland and running over a rough gravel road. I'd been looking for any signs of what happened along here. A memorial of some kind. A temple. A rusty vehicle

perhaps. I stopped at a cemetery but the graves were only 20 years old.

Soon, we came back upon the wide and shallow Ba River after its own exit

from the hills. From the bridge, I could see an old and partly torn-up

concrete ford. Another ambush site for sure.

When we stopped for lunch just afterwards at Chu Gu, Trang confirmed that thousands had died trying to cross the river here. We pushed on to the district town of Phu Tuc, also known as Krong Pa, where we stopped at a riverside cafe and stretched out our hammocks for a nap, the best siesta stop of the trip. With the road

in such tough shape, no one was looking forward to the next 80 kms into Tuy

Hoa.

By this stage, I was thinking that anyone from that column who'd got his far

-- or perhaps a bit further and closer to the Phu Yen provincial border --

would've been breathing a sigh of relief. The road was a patchwork of

gravel and pot-holed asphalt and I was frequently bottoming out on my

shock-absorbers. (Ouch!)

The valley widened out but most of the time we were struggling over one low hill after the other. More Montagnard villages appeared, these of the H'roi people. I'd never seen so much manioc with trucks loading up huge pink plastic bags of the smelly root vegetable for transport to market. (Manioc is eaten on its own but used for tapioca.)

Then, closer to the district town of Cuong Son, or Son Hoa), sugar cane

took over as the main crop and now completely dominated the valley in all

directions in what is surely Vietnam's largest sugar-growing region.

The harvest was in full swing -- some harvested by motorised brush-cutters but

mostly by old-fashioned machetes -- with the sugar cane loaded onto convoys

of ox-carts for transport up to the road and waiting trucks. (And the way

they were maximising the loads by jumping up & down on the sugar cane, I

could see why road was in such bad shape -- overweight trucks!) And then

with only 40 kms to go, the road was finally back to normal again and the

run down the valley to Tuy Hoa is one of loveliest in Vietnam. On the

right and marked by numerous sand banks and low hills on the the far side

were the wide waters of the Da River while on the left a fast-flowing

canal -- post-war, I'm sure -- kept us company as we wound our way toward

the town. Lovely villages. Coconut trees. Endless lush-green rice

fields.

And finally in the distance we saw Tuy Hoa's distinctive pyramid-shaped Chop Chai Mountain (391 metres) just to its north and then, as we got closer, the town's distinctive Cham tower on the river's northern bank. It'd been quite a day-long run down from Pleiku and, for me, the best day of the trip. Unlike so many in that column, we'd made it safely & sound. But I felt that I had paid my respects to those countless

thousands who died so tragically by simply making that journey -- and remembering them. I'd certainly felt their presence.

And now that I'd seen Route 25 -- formerly Route 7B -- first-hand, I've

managed to fill in the blanks. On the South Vietnamese column's actual

numbers, I've seen figures ranging from 160,000 to over 300,000 consisting

of military and government officials and their families, plus other

civilians. And where I'd sensed those NVA ambushes taking place was

correct.

But there was another one at that gentle pass of Chu Sre, referred to as Bleik Pass elsewhere, down into today's Ayunpa. The valley around what was then the provincial capital of Cheo Reo would've been dry, not irrigated, back then. When the NVA pushed in from Ban Me Thuot, they split the column -- which stretched all the way forward to the bottle-necks at To Na Pass, the river crossing at Chu Gu and beyond -- into two. South Vietnamese Rangers protecting the column tried to hold off the NVA but were hit by one of their own air strikes and collapsed in total disarray. One

can only imagine the horror and carnage of military and civilians caught up

in that disaster. Further on, lead elements of the column -- which included

South Vietnamese engineers and bridges -- ran into serious problems around

Cung Son.

South Korean troops had heavily mined the road from here straight into Tuy Hoa during the earlier war years forcing the fording of the Da River and a sitting target for NVA artillery.

The road straight ahead into Tuy Hoa where all that sugar cane grows today was unusable because South Korean troops -- who were stationed in Binh Dinh and Phu Yen up to the end of 1972 -- had seeded it with land mines and passage was just too risky. From here, the ARVN Rangers and Engineers, with help from VNAF Chinooks, pushed a ford across the Da Rang River to its southern side and with help from Regional Force troops out of Tuy Hoa overcame a series of NVA road blocks and ambushes to finally reach the coast. In the end, only 60,000 soldiers and civilians managed to reach Tuy Hoa with at least 100,000 stranded along the road. The retreat

had been a total disaster. The Fall of Saigon was now inevitable.