The Vietnamese Lunar New Year - Tết - came well into February in 1975 with the South Vietnamese cautiously welcoming in the Year of the Rabbit, now two years into the Paris Peace Accords’ cease-fire which surreally was mostly working. What? Driving at night? Vietnam was eerily quiet. All the world’s attention was focused on neighbouring Cambodia with Phnom Penh now totally surrounded and kept alive by a dramatic mini-Berlin Airlift of cargo aircraft spiralling bravely down into Pochentong Airport to avoid anti-aircraft fire & shelling, unloading and taking off again. For Hanoi, the timing was perfect.

With next month’s 50th Anniversary of the Fall of Saigon, I now jump ahead in excerpts from The Bite of the Lotus: an intimate memoir of the Vietnam War to bring you back to exactly those days 50 years ago today.

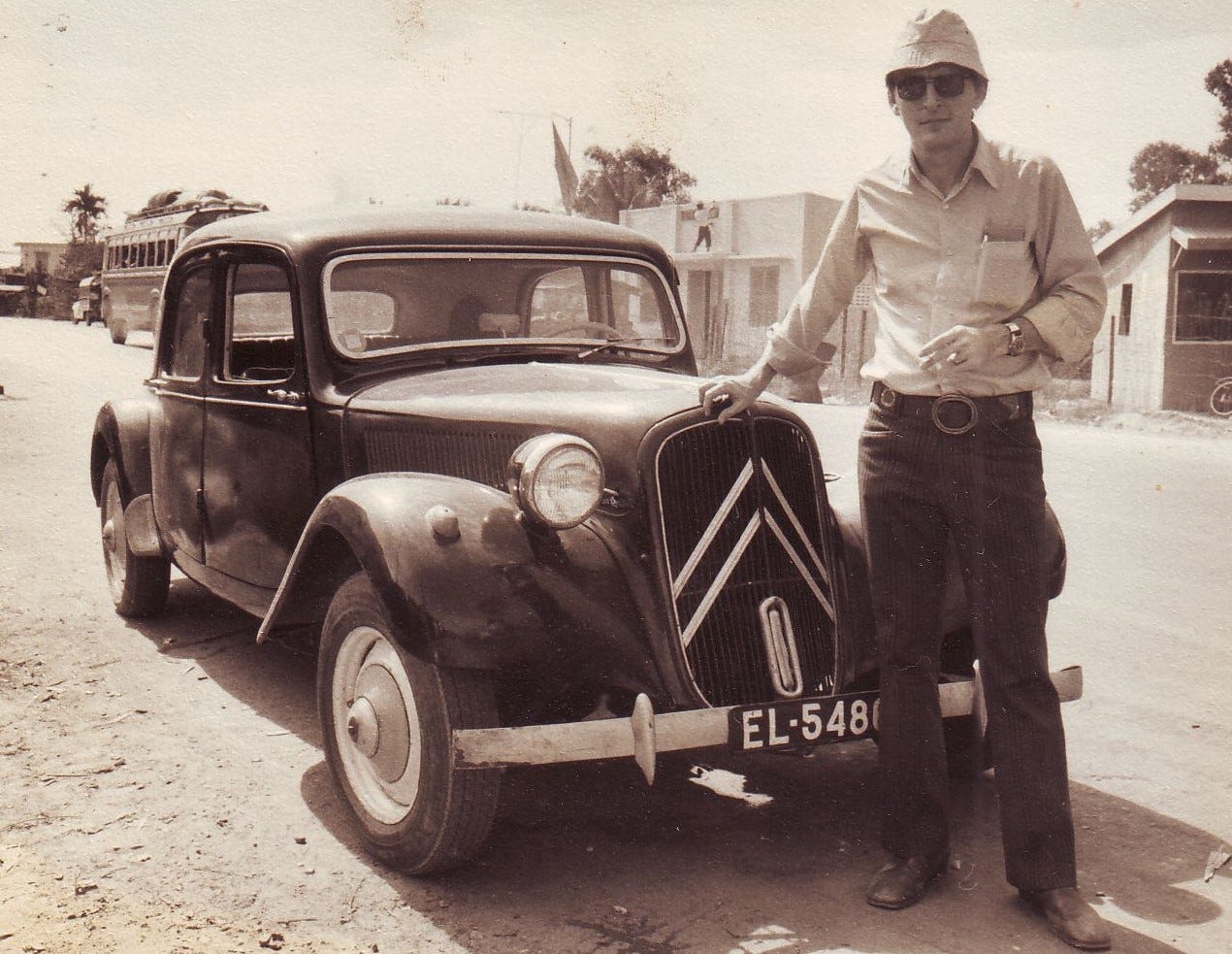

Everything went quiet for another Tet, and the Year of the Rabbit. Kim-Dung and the kids were already down in Go Cong, and on Tet eve I was working late but finally got away in the Citroen with Kim-Dung’s younger sister, Oanh, who was at school in Saigon. Concerned the ferry over the Vam Co River would be closed, I headed down the familiar road to Mytho, arriving there at dusk with Go Cong still 35 kilometres away.

I was the really proud owner of this Citroen 11N (my very first car, in fact) and loved squealing around the streets of Saigon after-curfew like in a French detective movie. (I had a special pass.)

During all my years in South Vietnam, I’d never driven on a road after dark, when government troops retreated into their fortified outposts and the VC owned the countryside. But this was Tết and I had to be with the family at midnight. With the Citroen’s wobbly headlights barely brightening the deserted road ahead, I pushed on to the Cho Gao Canal, its quaint old ferry now replaced with a high US-funded concrete bridge. I waved to some surprised soldiers at its peak, before the long, straight run into Go Cong.

Slightly annoyed at my lateness, Kim-Dung was happy that we were all together to welcome in one more year. And what would it bring? We sure didn’t see or hear any rabbits.

* * *

I’d barely got back to the office after Tết before I was rushed over to Phnom Penh, where things were rapidly deteriorating. The last river convoy had fought its way up the Mekong, its low dry-season waters overlooked by high riverbanks now crawling with well-armed Khmer Rouge guerrillas, who picked off the freighters and barges like sitting ducks.

The Cambodian capital was now encircled and under siege, with more captured artillery and rockets landing on the city. AP had four staffers on deck: me, Bangkok bureau chief Richard Blystone, stringer Matt Franjola and Saigon’s Denis Gray.

To keep the refugee-swollen city alive, a mini Berlin Airlift of rice, fuel and other essentials cranked up. An incredible assortment of propeller-driven aircraft dropped steeply into Pochentong, their cargoes were speedily unloaded beside sandbag revetments, and they roared off again. Ammunition arrived the same way.

An air of desperation gripped Phnom Penh. But every night, a hardy corps continued down to Chantal’s for a few relieving pipes of opium. To cut the edge during the day, I slipped into a rough den I’d found in Phnom Penh’s Chinatown for a few siesta hour pipes.

The conversation around the dinner table and the opium den was not so much about how much longer Phnom Penh would last, but who would replace the Lon Nol regime. The US embassy’s press office was flogging stories about how vicious things were in Khmer Rouge–controlled zones, which, of course, were increasing by the day. Summary executions, forced labour, fanatical child soldiers. But after all these years of official bullshit, most journalists didn’t believe them – or didn’t want to.

When Matt did write about real life in Khmer Rouge territory, supplemented by his own intelligence sources, the story got little play. Predictions of a bloodbath after a Khmer Rouge victory were vehemently denied by the exiled Sihanouk. But no one even knew for sure who was leading the Khmer Rouge, a faceless bunch the prince had once sent into exile. Things wouldn’t be that bad, we thought wishfully, when this horrible war in Cambodia ended. Surely, the still widely revered Sihanouk would fix things up.

With Phnom Penh now under siege, we were flooded by fact-finding congressmen and women deciding the fate of Cambodia & South Vietnam and whether to keep funding them or not.

With the US Congress now ostensibly deliberating on President Ford’s urgent request for Cambodia and South Vietnam, we were swamped with fact-finding congressmen – and even more colourful congresswomen, with the appearance, first in Saigon and then in Phnom Penh, of the perpetually broad-hatted Bella Abzug, a Democrat from New York, and the severe, pipe-smoking Millicent Fenwick, Republican from New Jersey.

The place was going down the gurgler, and now these clowns showed up? How seriously were we supposed to take them? Well, not seriously enough, apparently, as New York was soon badgering us about every bit of copy on the visitors, and coming down heavy when we lost play to UPI. Our morale plummeted.

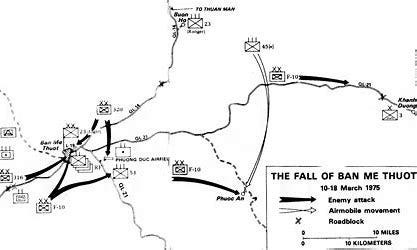

I’d been in Phnom Penh for three weeks in early March 1975 when Esper messaged for my immediate return to Saigon. The provincial capital of Ban Me Thuot in the southern Central Highlands, and another 130 kilometres north-east of Gia Nghia, was under massive NVA attack from across the Cambodian border. It sounded a lot more serious than the Battle of Phuoc Long.

(See my earlier ‘Vietnam’s 50th - a Missed Message’ post of 10 January 2025.)

Ban Me Thuot was the southernmost of the highlands’ three major cities, with Pleiku and then Kontum further north, both major targets in the 1972 offensive and their surrounds the scene of post-ceasefire fighting. No one expected an offensive that far south.

With seats now almost unobtainable on the few commercial flights still servicing Phnom Penh, Blystone called the US embassy and got me onto an afternoon Air America chopper heading back to Saigon. I hastily packed up and got a lift out to the unfamiliar military side of Pochentong, where the Cambodians based their handful of helicopters and propeller-driven bombers. A derelict Soviet-made Mig-17 from Sihanouk’s neutralist days sat nearby.

Saved by Air America. With South Vietnam’s southern highlands Ban Me Thuot now under NVA (North Vietnamese Army) attack, I needed to rush back to Saigon and what became the total collapse of the country over the next six weeks. (This is a file photo from inside South Vietnam.)

As we approached, we heard an explosion and then saw black smoke rising from one of the tile-roofed buildings. More incoming Khmer Rouge artillery. We stopped and waited for a second round. Nothing more. Approaching closer, I saw the grey chopper with its dark-blue Air America livery firing up outside an open hangar. I jumped out of the car, grabbed my bag and ran for it. I was the only passenger.

I hadn’t been on a chopper in ages – not since that crowded ride back down that steep-sided valley out of Khe Sanh as South Vietnam’s invasion of Laos was collapsing four years before. If you rode these critters long enough, you’d inevitably start wondering about the odds. I’d lost too many friends on them. The old Air America UH-1B rose higher and higher over Pochentong and Phnom Penh. I’d never been up this high. The pilot was clearly worried about Strelas, or Soviet-made shoulder-held SAM-7 rockets.

As we clattered along through the clouds, I could barely make out the familiar line of the Mekong River through the haze below. When we neared the South Vietnamese border, I wondered once again what’d happened to my friend Sean Flynn, who’d disappeared down there in 1970. Was he still alive somewhere? We landed in Saigon, and I hopped out, thanked the crew and hailed a taxi home without even getting my passport stamped. After quickly hugging a surprised Kim-Dung, I jumped on my Kawasaki and rode to the office.

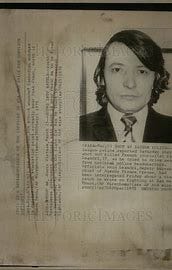

A horrible death for my AFP colleague Paul Leandri who was shot at South Vietnam’s Police Headquarters after he angrily left an interrogation and died in a hail of bullets driving away. I think him often when I pass what is now the southern police headquarters of the winning side.

The battle for Ban Me Thuot was still going, and things weren’t looking good. Only the day before, Paul Leandri, an AFP correspondent with whom I’d shared a few pipes over in Phnom Penh days before, was called to the South Vietnamese police headquarters to explain his story that dissident tribal Montagnards had joined the NVA attack. President Thieu was personally angry. Leandri refused to reveal his sources, trashed the office and, in a fit of anger – aggravated, I’m sure, by his edginess coming off the opium – jumped in his car and was shot to death while driving full-speed towards the entrance. What a shock – and hardly the PR the Thieu government needed.

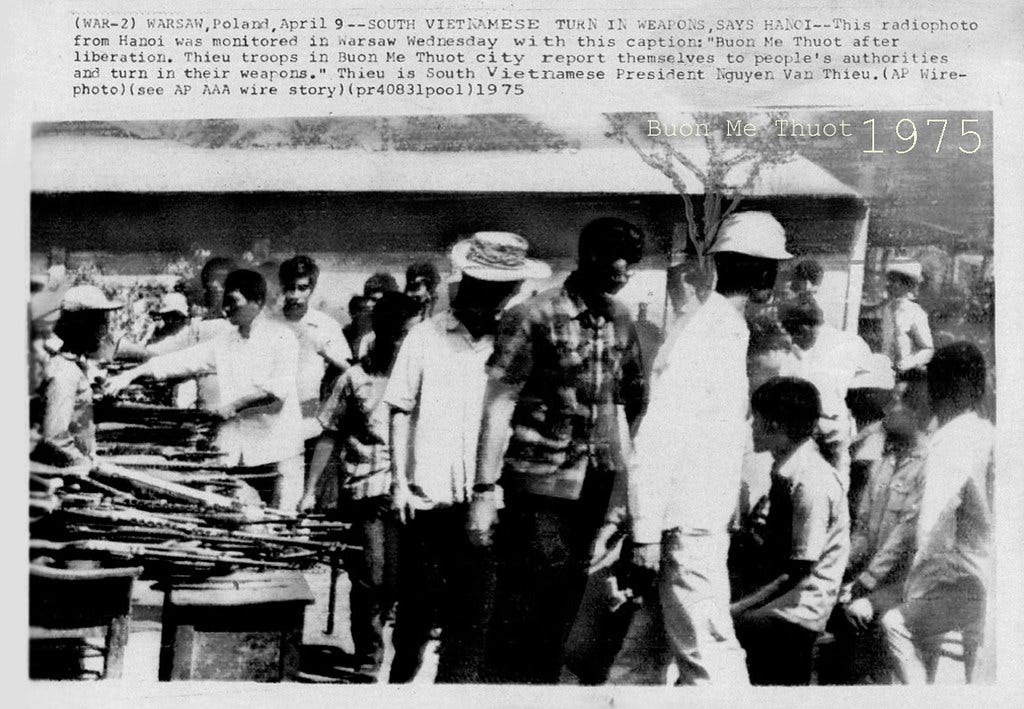

Now the penny dropped for me. That January attack on Phuoc Long was just a try-out by the North Vietnamese to see if the Ford administration would intervene militarily if hostilities resumed in violation of the Paris Agreement. Clearly, the Americans hadn’t responded, and the Democrat-controlled Congress was now more recalcitrant than ever. After Ban Me Thuot fell following several days of heavy fighting, the legislators rejected President Ford’s request for supplementary assistance for South Vietnam and Cambodia. The rout began.

For more, see Wikipedia on the Battle of Ban Me Thuot.

In later years, I always flared in anger when someone who wasn’t there says something like, ‘I always knew South Vietnam would fall.’ Yet for us, living and working through the next five weeks day by day, everything was incomprehensible. After so many years in South Vietnam, I simply couldn’t allow myself to acknowledge what was happening.

And so, just like Phuoc Long only two months before, Ban Me Thuot fell. This time the scale was even more dramatic, with the NVA – backed by tanks, anti-aircraft guns and long-range artillery – surprising and then overwhelming the South Vietnamese defenders. Many ARVN stood their ground, but more just upped and ran, concerned about their families. Civilians joined them. A counter-attack briefly raised hopes but then fizzled out. The Communists now boasted thousands of ARVN prisoners.

The southern Central Highlands were gone. We briefly wondered if the North Vietnamese were just improving their infiltration routes south along Route 14, closer to Saigon, and might settle for that. But Pleiku and Kontum further north were now isolated and cut off from the coast.

Thieu secretly ordered the evacuation of his major units from the entire Central Highlands. At the same time, even the northernmost region around Danang and Hue would be sacrificed with the withdrawal of the elite Airborne Division, in what the former general and now president called a strategy of ‘light at the top and heavy at the bottom’. The more densely populated Saigon and the Mekong Delta would hold on for one last fight.

But the Americans weren’t told of this plan, and we soon heard rumours of something dramatic happening up in the Highlands, especially around Pleiku. Air Vietnam flights were full. The VNAF was pulling out its families. Civilians were packing up to flee. And then growing numbers of military units began heading out. Wholesale panic grew.

With Route 19 to Qui Nhon on the coast blocked by the NVA, the columns headed diagonally down the little-used Route 7A, through the Phu Bon provincial capital of Cheo Reo. With Ban Me Thuot less than 100 kilometres south-west, and NVA troops now moving north along Route 14, the South Vietnamese hoped they might slip past before their escape was discovered.

Soon enough, however, the 180-kilometre run down to the coast at Tuy Hoa turned into what the South Vietnamese began calling ‘the road of blood and tears’, as the NVA discovered the ruse and wheeled around in pursuit, setting ambushes at critical pinch-points and bringing in devastating artillery fire.

The fate of the column of refugees was unknown for ten agonising days, before they straggled into government lines. Only 20,000 out of 60,000 soldiers survived, and 100,000 of the 400,000 civilians who fled Pleiku and Kontum. It was a gut-wrenching story, and the worst slaughter of the war.

A few years ago, I took a motorcycle down Route 7A - today’s Route 25 - from south of Pleiku to Tuy Hoa on the coast and could sense the ghosts of the thousands of South Vietnamese who died along this road fleeing the Central Highlands in March 1975. Quite an eerie experience.

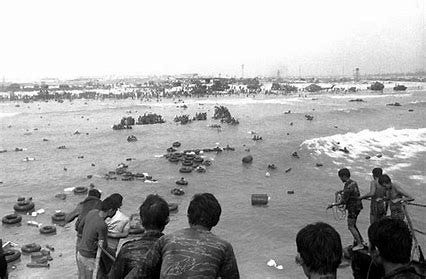

Meanwhile, the panic was on further north as the former royal capital of Hue was abandoned on 25 March virtually without a shot being fired. With a million refugees before them, the NVA moved quickly south over the soaring Hai Van Pass and brought the port city of Danang under artillery fire. Soldiers fled in panic, most famously on a World Airways Boeing 727 flown in by the company’s flamboyant owner, Ed Daly, with some clinging inside its wheel-well all the way back to Saigon.

At the port and nearby China Beach, thousands of military and civilians crowded onto huge barges and pulled out to US-chartered freighters off the coast. My AP colleague Peter O’Loughlin, flown up from Sydney, was on one of the ships as the rowdy and undisciplined mob were lifted aboard in cargo nets. Fights broke out in the hold, with grenades thrown. Plans were drawn up to drop the refugees from these and other fallen coastal cities on Phu Quoc Island in the Gulf of Siam, off the south-east coast of Vietnam; it had previously been a wartime POW camp for VC and NVA.

By 1 April 1975, just 20 days into the offensive, the NVA were roaring down coastal Route 1, with Binh Dinh and Qui Nhon fallen, and then, just after the escapees from the Central Highlands arrived, Tuy Hoa too. Over in Cambodia there was bad news too. The Mekong River town of Neak Luong fell, and President Lon Nol fled into exile, first to Bali and then Hawaii. The US embassy in Phnom Penh advised all Americans to leave.