1974: South Vietnam Loses the Paracels as the Khmer Rouge Tighten the Noose.

GRUMPY OLD VIETNAM HAND.

As I said at the end of my last excerpt from The Bite of the Lotus: an intimate memoir of the Vietnam War, “It seemed the world simply wasn’t very interested in Vietnam anymore.” As the first year of the Paris Peace Agreement drew to a close in January 1974, we were scrambling to find enough stories to keep AP’s already cut-back Saigon staff occupied.“ But then, I was spending more time on the road, especially in Cambodia, where the Khmer Rouge - with U.S. air attacks now banned by Congress - were tightening the noose around Phnom Penh. I was now writing as well as shooting photos as the situation worsened.

The Quaker-run Quang Ngai Rehabilitation Centre for civilian war victims. (Photo by Phillip Jones Griffiths.)

After the busy pace of the war before the ceasefire, we were now scrambling to find enough interesting features for the wire – and to justify our continued presence in Saigon. I travelled with Denis Gray up to central Quang Ngai Province, a grimly cold and drizzly place, for a feature story on a rehabilitation centre for civilian war victims. It was run by Quakers, kind Americans who reminded me of missionaries in the Congo where I’d grown up. And then it was back to Cambodia for a year-end feature on Indochina’s continuing internal refugee problem, a three-part double by-line project with Tad Bartimus.

Our Christmas of 1973 was my most pleasant in years, as Kim-Dung baked a turkey dinner – her first ever – which we shared with my freelance photographer friends John Giannini, who was staying with us, Yves Billy and his girlfriend, Francoise DeMulder, down from Laos, and Denis from the office. My folks gifted me I’m OK, You’re OK by Thomas Anthony Harris, a popular self-help book using the author’s ‘transactional analysis’ approach to solving life’s problems. Like many such books, it had some kernels of wisdom.

We then headed up to Hong Kong on another R&R with the kids for New Year’s Eve, and back through Bangkok. Photographer Neal Ulevich was away covering Japanese prime minister Kakuei Tanaka’s visit to Indonesia, and things were busy, especially in Cambodia. Already a morose and unlucky fellow, Giannini took a round through his left hand after returning there to freelance.

Just before the first anniversary of the ceasefire came another Tết on 23 January 1974, the Year of the Tiger, and I headed down to Gò Công on the eve of the lunar new year for just an overnight stay with the family.

China also chose that moment to attack and occupy the South Vietnamese–held portions of the Paracel Islands (Hoàng Sa) in the South China Sea, roughly 200 nautical miles east of Danang. News of the ensuing naval battle on the remote archipelago, which we barely knew as part of South Vietnam, was slow getting out. But when I returned to the office in the early afternoon of the first day of Tet, AP Bureau Chief George Esper was in a panic. He had an urgent story on the battle and the office’s teletype operator was nowhere around.

No doubt the operator had left to spend time with his family at Tết; when his replacement arrived a few minutes later, George tore into him. The neatly dressed man wordlessly took the copy George was waving about, sat down and started punching away at the teletype machine.

I felt totally sorry for the guy. George was married to a Vietnamese woman, and had spent years in the country – didn’t he know anything about Vietnamese customs? Everything you say and do on the first day of Tết determines the year ahead. My respect for Esper dropped a lot after that incident.

And then all those dreadful one-year anniversary pieces on the Paris Agreement – how I always hated those editorial contrivances – before the overnight Khmer Rouge shelling of Phnom Penh’s Pochentong airport took me back into Cambodia to conduct a ‘workshop’ on night picture techniques for our little army of freelance photographers, mostly locals.

M79 Grenade Launcher & Proximity-Fused Rounds—The M79, nicknamed “Thumper,” fired 40mm grenades with a proximity fuse, designed to detonate upon nearing a target. Widely used in Vietnam and Cambodia.

One day our Cambodian reporter, Chhay Born Lay, heard about a Cambodian Army soldier with an unexploded M79 round stuck in his jaw. The damned thing could blow at any moment, but a gutsy military doctor was planning an open-air operation the next day. Would I be interested in covering it? Sure.

We drove down to a military hospital inside Phnom Penh’s Olympic Stadium, a grandiose structure from Sihanouk’s glory days, and grabbed a hasty quote from the poor fellow, who, unlike others in the crowded wards, had his own room and was shaking in fright. We wished him the best for the operation, and returned the next morning to see a heavily sandbagged makeshift operating platform set up in the middle of the playing field. A sand-filled bucket stood to one side.

With great care, the unfortunate soldier was brought out on a stretcher and set down on one side of the wall of sandbags. As hundreds of hospital staff and patients looked on from a safe distance, the solitary doctor – wearing a flak jacket and full operating regalia, including gloves and mask – walked out and took his position on the other side. I crept as close as I dared with my cameras.

The only sound was blowing dust and sand as the doctor’s hands moved through a hole and he began the operation. After several long minutes, the doctor suddenly leapt to his feet, holding the unexploded round in the air. The crowd burst into applause as he ran for that bucket of sand, shoved the round inside and then stood back, clasping his hands together in the Cambodian style and bowing. What a performance. And I had pictures too!

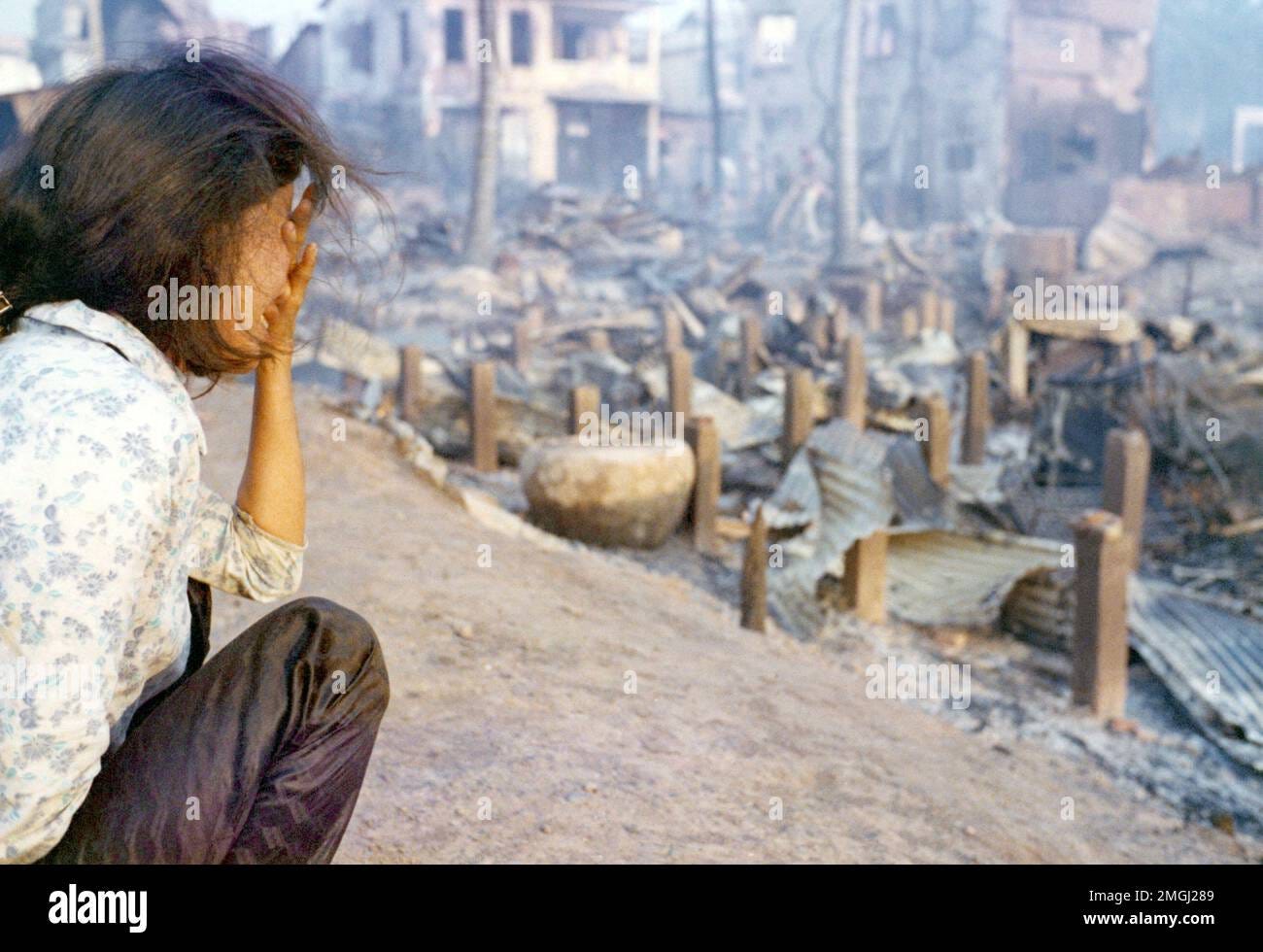

Back at Le Phnom before lunch, I was about to write the story and find a ‘pigeon’ to carry the film to Saigon when the familiar sound of incoming artillery shook the ground. Everyone rushed outside, jumped in cars and headed towards the sound. The entire southern edge of Phnom Penh was ablaze, a tightly packed and highly flammable bidonville of refugees from the surrounding countryside. A few old French-built fire trucks had shown up but could do little as flames leapt high into the sky, followed by thick black smoke, as thousands of Cambodians fled towards us in panic. What a disaster. I wandered into the wreckage, shooting both in black and white and colour.

At one point I saw a couple of colleagues helping Dennis Cameron, an American freelance television cameraman, out of a water-filled crater, but I didn’t think too much about it until I heard later that he was medically evacuated to Bangkok. The water in the crater was boiling hot and he’d been horribly burned.

The aftermath of the huge fire that swept through the shanty town of southern Phnom Penh after a devastating Khmer Rouge attack with captured US artillery. The Cambodian capital was now effectively surrounded.

We completed our story on the Khmer Rouge’s worst-ever artillery attack on Phnom Penh, estimating that about 200 civilians had been killed and at least 300 wounded, and shipped out the film, including those of our freelancers. An area the size of four football fields had been turned to ashes, and the injured were being stacked up on cots in already overcrowded hospitals.

We dropped around to the American Embassy to receive a background briefing from the US Ambassador, Thomas O. Enders, though it was on such deep background that we couldn’t even attribute it to Western diplomats.

The Khmer Rouge had captured several US-made 105-mm artillery pieces from fleeing Cambodian troops, and had turned one of the guns onto Phnom Penh. The first rounds fell near more-or-less legitimate targets – like Lon Nol’s presidential palace and the US Embassy. But when the gun rotated to its furthest point and stopped, the Khmer Rouge had simply fired off all their remaining rounds, pummelling the city’s tightly packed slum district and touching off that conflagration.

Sitting at his desk in his air-conditioned office, the tall and bespectacled ambassador was regarded as sophisticated and intelligent. But when one of the correspondents asked why the Khmer Rouge would deliberately target civilians, he said Cambodians had a ‘different view towards life’ – a variation on the old cliché that ‘life is cheap in Asia’.

I seethed in anger at his callousness; my New York Times colleague Syd Schanberg, later the inspiration for The Killing Fields, recalled years later how my knuckles turned white as I gripped the arms of my chair.

Where had those damned guns come from in the first place? Who was really treating life cheaply here? Fucking bastards.

Thanks for that. I assume the photos without attribution are your own.