Yes, I was also at Ho Chi Minh City’s 50th Anniversary parade yesterday for the Fall/Liberation of Saigon on 30 April 1975 - and took pictures too, but I’m still mulling over what to say, especially about all those VC flags that appeared out of nowhere after 50 years. (Hmm. The Viet Cong didn’t do so well either after the war.) Plus, everyone’s really happy! So while I think what to say, let’s go back 50 years after my landing on that US Navy ship in the South China Sea after fleeing Saigon the day before and what was happening out there.

So here’s another (relatively short) excerpt from my unpublished work from 10 years ago and illustrated with photos I took at the time, but only realised I had - or forgot I had - as I was writing this. (This then is a continuation of The Bite of the Lotus: an intimate memoir of the Vietnam War which you can now read in its entirety, well almost all, by Subscribing and scrolling down through when I began in August 2024.)

Everyone who escaped during Operation Frequent Wind has their own personal story and this is mine, one of 1,373 US citizens who officially left Saigon by helicopter that day, so a rather small cohort of escapees.

That night and subsequent ones aboard the USS Mobile, I crashed on a couch in the captain’s quarters while Ann Mariano, wife of ABC newsman Frank, slept in his cabin. (He was reputedly a submariner who preferred a more confined sleeping space up on the bridge.) I wasn’t hanging out with the other journalists on board but a couple with whom I’d previously had a nodding acquaintance drifted into our space over the next day or so, Arnold ‘Skip’ Isaacs of the The Baltimore Sun and an Australian named Bruce Wilson from the Melbourne-based Herald & Weekly Times Group.

I didn’t have much money and Bruce kept me stocked with packs of Camel Plains after my last Saigon-made Bastos ran out. We ate meals in the galley and I had a paperback of James A Michener’s dreary The Drifters, a tale of dropped-out hippies from this now terminal era. (I never did finish that damned book.)

On board the small landing craft carrier USS Mobile, we were in a vacuum with no news. A couple more helicopters landed. But out on deck all through the night, we could see and hear them overhead and landing on larger vessels further down in the flotilla. (Most journalists ended up on the USS Okinawa, a helicopter carrier, and then transferred to the USS Blue Ridge.)

At dawn on Wednesday, the 30th of April, everything was eerily quiet. I could see Vinh and Phuong’s (who’d been taken away from me the night before, see previous post) freighter nearby. We had breakfast and wondered what the day would bring.

Accompanied by my Third Force friend Ly Qui Chung (R), the Minister of Information, South Vietnam’s barely-inaugurated President Duong Van ‘Big’ Minh is led to his surrender by victorious North Vietnamese soldiers in what was then the Presidential Palace, today’s Reunification Palace in Ho Chi Minh City. A sad and tragic moment. (AP photo)

In the late morning, Ann told me the latest news. South Vietnam’s President Duong van Minh, “Big Minh,” whose inauguration I’d attended only two days ago had gone on Radio Saigon and ordered a complete surrender. North Vietnamese troops were moving into Saigon. Everything was over.

Choking back tears, I walked upstairs past the bridge and then outside as high as I could climb just below the USS Mobile’s mast and funnel. I tried making out the Long Hai Hills behind Vung Tau. A last glimpse of Vietnam. But nothing. Just grey everywhere. Slumping down on the rough metal stairs, I felt horribly alone. Lost. I broke down and cried. Lunch. A fitful nap. That boring novel. Another hit of smack.

Then as dusk settled over the evacuation flotilla, at least 25 South Vietnamese air force helicopters suddenly appeared out of bases in the Mekong Delta which, unlike Saigon, had not yet fallen to North Vietnamese troops.

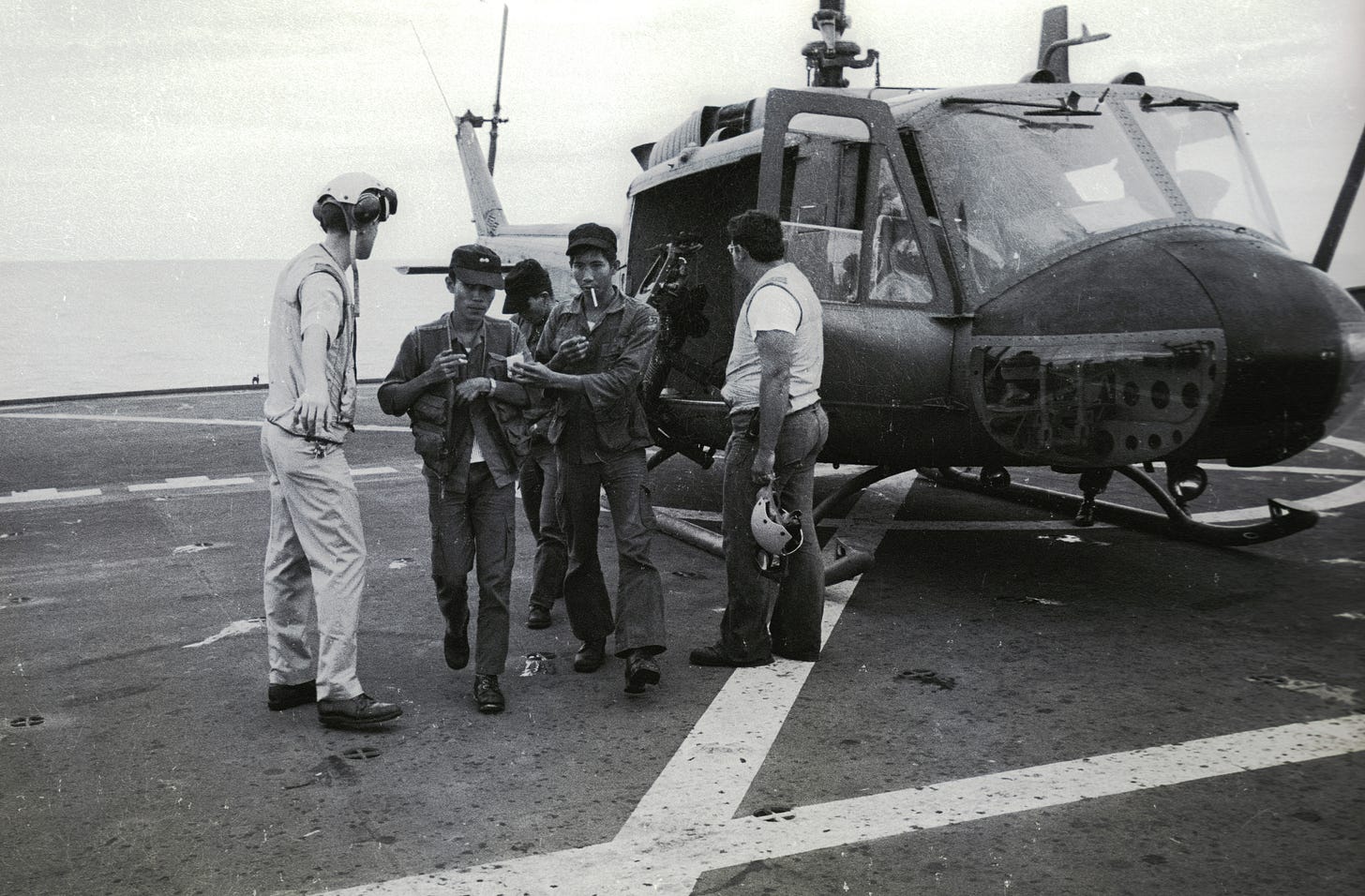

And dying for a smoke too, a VNAF (South Vietnamese Air Force) helicopter crew out of the Mekong Delta which landed on the USS Mobile, one of over a couple dozen who appeared over the evacuation fleet on the day of Saigon surrender.

“Our president said not to fight anymore,” one young US-trained pilot told me. “So we threw away our guns and flew away.” Some had time to pick up their families but others took off leaving them behind.

The flotilla had already cut back from the previous day to only a score and most of the VNAF choppers landed on the USS Midway, converted from a regular to helicopter carrier for the evacuation. The crews were disarmed and their aircraft tossed into the South China Sea.

When a South Vietnamese helicopter gunship settled down onto the USS Mobile’s landing pad, a flak-jacketed US Marine approached with shotgun upright on his shoulder. The crew simply smiled and handed over their personal weapons. Several minutes later, the chopper and its expensive US-made mini-guns and rocket pods went over the side.

Then other airmen and families arrived from the Midway and after American-style Chop Suey & Rice were transferred to Vinh and Phuong’s freighter still a short distance away.

The end of this story for AP included an advisory to NY that I’d be at sea at least a couple more days before heading to Subic Bay. I also included a personal note to Bangkok to advise Kim-Dung about my forced separation from her brother and niece but they were in good hands with Colonel An and heading to Guam.

I advised her to stay in Vientiane until I disembarked in the Philippines. “Greatly saddened no more of family could depart,” I ended in wire service lingo, “as everything turned out so wrong and fast. Love, Robinson. Endit. AP.”