Vietnam's 50th - Stuck in the South China Sea on the USS Mobile, and then a medical emergency.

GRUMPY OLD VIETNAM HAND.

I left my personal memories of 50 years ago down in the South China Sea where I heard of the Fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975 aboard a US Navy ship after the previous day’s now-famous helicopter evacuation, found a quiet place and cried. Just like this year, the 30th was a Wednesday and our ship remained off the coast until the weekend picking up the first Boat People before we were finally transferred to Operation Frequent Wind’s command ship, the USS Blue Ridge, and finally by chopper into Clark Air Base in the Philippines. But hardly to safety as my life now quite literally collapsed around me. A personally tragic time.

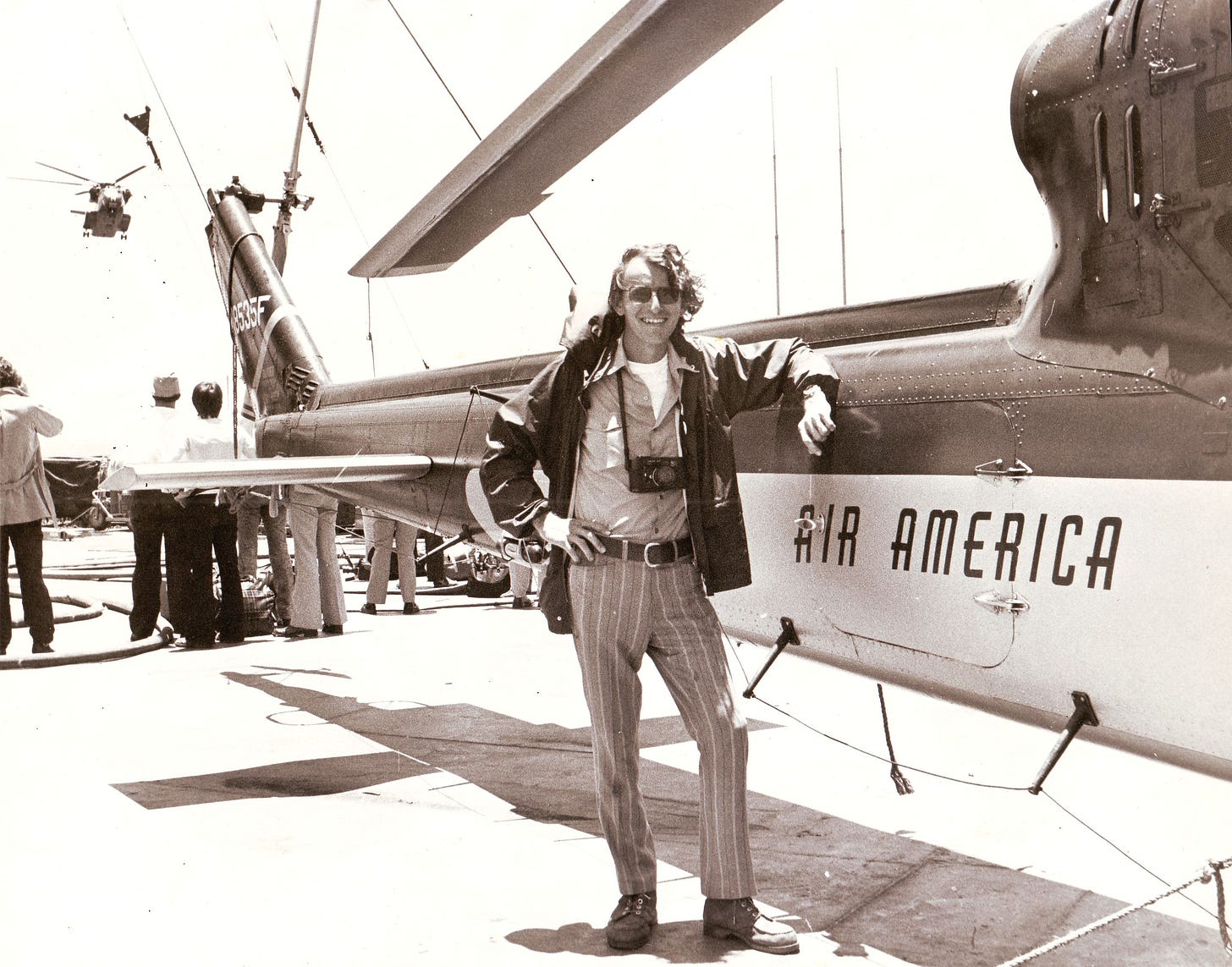

As phoney a smile as one could imagine as I waited aboard the Command Ship USS Blue Ridge for CH-53 helicopter east to Clark Air Base in the Philippines, now five long days since my evacuation from Saigon and its fall on 30 April. I had no idea of what lay ahead in my life. And do pardon those trousers! That was the style and all I had fleeing Saigon.

And so now more excerpts from those days of anguish from my unpublished memoir about my life after The Bite of the Lotus: an intimate memoir of the Vietnam War which ends my helicopter escape from Saigon on 29 April 1975 and excerpted here on my Substack. (Still to come, excerpts from chapters of the 1973-75 Ceasefire Period in South Vietnam, including explaining - I hope understandably - the addiction to which I refer so openly below. Those were them days back then.)

I woke up the next morning after 30 April 1975 overwhelmed by depression. I didn’t want to talk to anyone. What was there to say? Eleven years and a whole life down the gurgler. No messages arrived. I’d smoked my last Bastos and now on those Camel Plains I’d bummed off Bruce Wilson, an Australian correspondent with The Herald & Weekly Times. My stash was running out. I was going off Cold Turkey, not just the heroin but Vietnam too. The stomach cramps. Sweats. A general malaise.

And the USS Mobile wasn’t going anywhere. For the next couple days, we lingered off the coast picking up the first “boat people” fleeing the communist take-over. Looking out from the back deck, the entire horizon was filled with vessels of all shapes and size, but mostly small fishing junks, making their way towards us where they were met by the Mobile’s landing craft, scuttled and their passengers transferred onto now a half-dozen freighters a bit further away. The Task Force’s radio net crackled with pleas for rescue and asylum, including a barge with 600 South Vietnamese paratroopers on board.

Aboard the USS Mobile was quite a large contingent of foreign correspondents, including in foreground NYT’s Malcolm Brown and Fox Butterfield with Arnold ‘Skip’ Isaacs of the Baltimore Sun to the left. The first Boat People were pulling up alongside our landing craft carrying freighter who were offloaded and their boats set on fire.

The journalists on-board the USS Mobile were becoming increasingly impatient and demanded a helicopter over to the fleet’s command ship, the USS Blue Ridge. But with the Philippines still way out of chopper range and the carriers – with some journalists on board - already heading east, I couldn’t understand the rush. But for a laugh and mild-mannered protest, Skip Isaacs (Baltimore Sun)and others bought and distributed white t-shirts from the ship’s on-board PX with the felt-tip slogan, “Free the Mobile 13!”

Late on the Friday as the setting sun reflected bright orange off a soaring cumulus cloud to our north and a pod of dolphins skirted up incongruously alongside, we finally headed east leaving behind just a couple other US Navy ships to pick up more refugees.

In one last story from the USS Mobile, I described the past couple days off the coast and noted early estimates that 20,000 Vietnamese had fled and were now also on their way east. I’d also determined that the freighter USS Sgt Andrew Miller with (brother-in-law) Vinh and (niece) Phuong on board was heading to Subic Bay, not Guam.

In an urgent message to Kim-Dung, I advised her to leave our children Laura and Alexander with brother Richard in Vientiane and fly to Manila, head over to Subic Bay and stop her brother and niece from entering the refugee pipeline to Guam. I estimated my own arrival in Subic aboard the USS Mobile a couple days later, or mid-afternoon on Sunday.

Operation Frequent Wind’s command ship USS Blue Ridge was a hustle of activity after those slow days aboard the USS Mobile. Not all helicopters were dumped into the South China Sea, including a couple from Air America and South Vietnamese Air Force (VNAF). We overnighted here before a CH-53 run east to Clark Air Base in the Philippines.

And then came another change of plans as a helicopter finally arrived the next afternoon and transferred our handful of foreigners over to the Blue Ridge. But only a few of the fleeing journalists who’d crowded the ship immediately after the evacuation of Saigon – and monstered a totally dejected US Ambassador Graham Martin in a disastrous press conference a couple days before - were still on-board.

After rolling the remnants of my smack into one last hit, I called Dennis Troute, an NBC Radio journalist with whom I’d always been friendly, onto an outside deck under the ship’s lifeboats as dusk settled over the South China Sea.

We shared our evacuation stories – his out of the already-infamous chaos of the US Embassy in downtown Saigon – and, in a moment he’d remember years later, I confessed my heroin addiction of the past two or three years. I was now going full-blown Cold Turkey.

After cruising eastward through the night, the Blue Ridge was close enough to the Philippines by mid-day Sunday - or a full five days after I’d flown out of Saigon – to “launch” us back onto solid ground but, in another change, now into vast US-run Clark Air Base north of Manila.

Pissed off was more like it. I refused to stand in line and shake hands with America’s last ambassador to South Vietnam, Graham Martin, and the commander of the Frequent Wind operation. What next in my life?

As we gathered on the command ship’s rear deck for the CH-53’s to arrive, the last American Ambassador in Saigon, Graham Martin, suddenly appeared along with the Task Force commander and began shaking hands and chatting with the waiting journalists. No way, I thought angrily, I’d rather throw the bastard overboard into the South China Sea. I moved away and parked myself glumly under the shade of an Air American “Huey” chopper until they’d moved along.

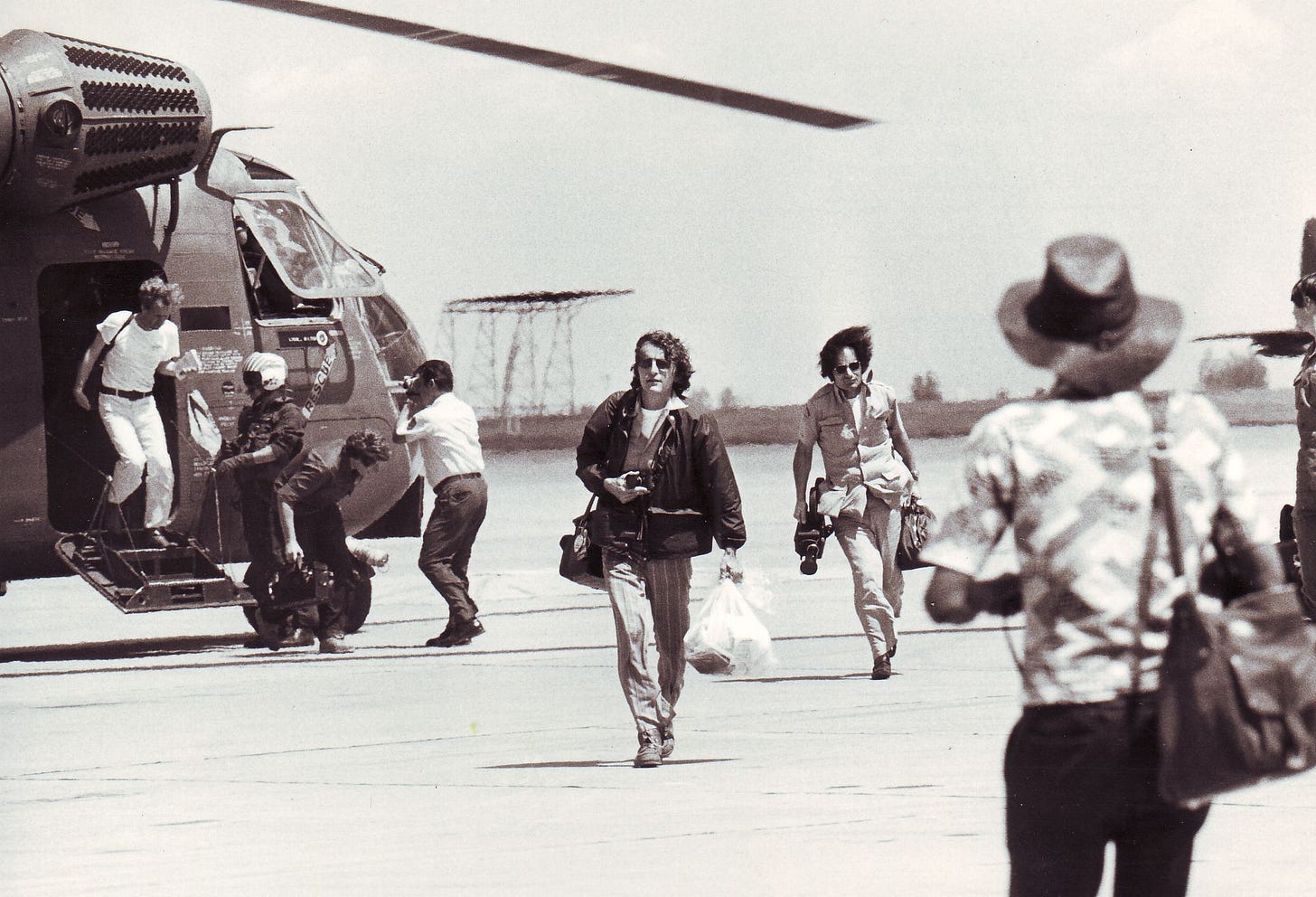

Finally, our CH-53 fluttered onto the deck and we boarded up for the hour or so run into Clark Air Base. My mind was a total blank. And then we were finally on the ground and I disembarked with my camera bag and a plastic bag of clothes and warmly embraced by Max Desfor, AP’s Tokyo-based photo editor, and Peter O’Loughlin now based in Sydney, Australia. What a relief!

Landing at Clark Air Base after my evacuation and the Fall of Saigon, now five days later on a Sunday, I only had my camera bag and a plastic bag of clothes and papers. Everything else was lost. My Vietnam Life left behind me.

All I wanted was a slice of apple pie a la mode. But when I asked my colleagues about those stories I’d filed from the USS Mobile – and especially those urgent messages for Kim-Dung – I was told they’d never arrived. Oh, damn! My wife had no idea what’d happened to me and her family.

A few hours later down in Manila, a city I’d never visited in my long years in Asia, I got through to Kim-Dung at Bangkok’s Montien Hotel where we always stayed on R&R. She only knew that I’d got out on the choppers but nothing further, not even a call or visit from the nearby AP office to see how she was doing. Zilch!

She’d gone into a total mental collapse and only thanks to a kindly room boy our two children continued to be cared for and fed. (She’s never forgotten, much less forgiven, AP’s treatment during those dreadful days.)

For the first time, Kim-Dung heard that her family were unable to escape before the Fall of Saigon but that I’d brought out Vinh and Phuong from whom I was then separated. My plan was to head down to Subic Bay the next morning, pull them off their freighter, get them travel documents and together head over to Bangkok to continue working for AP out of there.

No way was I heading back to the US. In the meantime, I told her to send Laura and Alexander up to the supposed safety of Vientiane in Laos with my brother Muk and join me in Manila.

At mid-morning the next day, now Monday, a Filipino driver in a black four-door late 50’s Buick picked me up at my Manila hotel and we headed west toward Subic Bay, a good three hours away. The city gave way to open rice-growing country with a distant backdrop of volcanic hills. I’d known and worked with a lot of Filipinos back in South Vietnam but felt little fascination with what I was seeing.

Sure, I’d heard plenty of yarns of raucous Manila R&Rs from colleagues and followed the rise of the country’s youngish-looking dictator Ferdinand Marcos and his colourful wife Imelda, but my knowledge of the Philippines was more simply historical. We were following the route of the famous Bataan Death March as thousands fled Manila following Japan’s surprise December 1941 attack on this then-American colony.

By early afternoon, we were heading down the main street of Olangapo with its colourful girlie bars, massage parlours and restaurants on a plateau with glimpses of vast Subic Bay below, its steep walls reminding me of a flooded cordillera. At the entrance to the huge US Navy base, I showed my passport and was directed to a press information centre set up inside the main officer’s club with spectacular view out over the entire facility, harbour and mountains beyond.

Considering how little clothing I had on fleeing Saigon, I was neatly dressed but left my heavy three-quarter Hush Puppies behind in favour a pair of thongs. But as I walked towards the club entrance, I blew out one of my flip flops and staggered awkwardly – and embarrassingly - inside.

In the aftermath of the Fall of Saigon, the story now focused on the first Vietnamese refugees with the arrival of contracted freighters like the Sgt Andrew Miller who’d picked up thousands in the South China Sea over the past week, including Vinh and Phuong. Desperately, I hoped I’d beaten the ship to Subic Bay and could now pull them out of the pipeline before they were flown to the main processing centre on Guam, a long 2600km to the east.

The press centre was hardly busy and I wondered why they’d even bothered setting one up. But eventually a white-uniformed US Navy Public Information officer came out and agreed to track down the Sgt Andrew Miller and its passengers. At the bar, I bought a cup of tepid American-style coffee and sandwich and waited, staring blankly out through those huge picture windows at the lush tropical scene. Eventually, he returned and perfunctorily announced, “The ship arrived two days ago and everyone on board was flown to Guam. There’s no one left.”

The hopes that’d kept me going for days crashed in a heap. My gut was aching. I headed into the toilet but couldn’t shit. The pain got worse, now just below my belt on the right side. I staggered back out into the main room and must’ve looked a sight. I was pale and my eyes teary. With no haircut for the past couple months, my slightly-dishevelled hair curled down over my collar. A hippie. Someone directed me to the US Navy hospital and I headed back outside to the waiting Buick dragging my broken flip-flop behind.

Lying on a bed in Emergency, the same sense of urgency as up at the press centre prevailed as I curled up in pain, gritting my teeth and groaning quietly. Finally, a young medical officer arrived, stretched me out, poked and prodded. I decided to confess – Doctor Confidentiality and all – that I’d been addicted to heroin back in Vietnam for the past three years and just gone off the last of that only a couple days before. After keeping me under observation for another hour, the doctor returned and said, “We can’t find anything wrong. You’re free to go.”

Back outside, the pain wasn’t much better and the driver was now increasingly concerned. Rather than drive straight back, he suggested staying overnight in a hotel, more of a flop-house for short-timers having a fling with the bar girls next door. A sleepless night. At dawn, we headed back to Manila with me now stretched out across the Buick’s wide back seat. The journey seemed to take forever.

Pulling up at the AP’s downtown office, I staggered inside and - with barely a second look – Bureau Chief Arnold Zeitlin yelled for me to head right away to hospital. Kim-Dung had arrived overnight and he’d advise her where I was heading.

As I got out of the car at the emergency entrance to Manila’s Makati Medical Centre, medical staff quickly grabbed me, placed me on a trolley and wheeled me inside. My right side felt like exploding any moment.

And suddenly, Kim-Dung was walking by my side. I hadn’t seen her for more than a month. No tears, just heavily concentrated concern. That beautiful smile. All I could say was they’re gone. Vinh and Phuong are in Guam. I missed them at Subic Bay. You’ve got to find them. “Don’t worry,” she said, “you’re going into the Operating Room now.”

When I woke up everything was dark outside. I was in a dimly-lit hospital room and Kim-Dung was quickly next to me, holding my hand. “You had an emergency appendicitis operation,” she explained softly. “They caught you just in time.”

Damned lucky too. Imagine if the appendix had burst overnight or on the drive back to Manila. Or earlier on that damned ship. Peritonitis for sure. I swore at that damned US Navy doctor back at Subic. Judgmental Bastard. But confiding my heroin addiction to the surgeon at Makati worked a treat and, as he later told me, he adjusted the anaesthetic – an opium derivative, of course – upwards and I was now on extra pain killers.

Groggily, I told Kim-Dung again what happened with her family back in Saigon on that fateful Tuesday just one week ago and how her father had come up too late and without her family. But for the first time, I also sensed blame from her. It was my fault. I hadn’t done enough after she left for Bangkok with her strict instructions to get them out on that “secret airlift.” What was the point of repeating, as I had at the time, that leaving was his choice? His decision, not mine. Sure, I already felt guilt and I was about to get saddled with a lot more.

But my main concern now was finding – and stopping - Vinh and Phuong in Guam and still pull off my plan to hang around in Southeast Asia. We’ve got to find them, I kept repeating. The kids were safely up in Laos with brother Muk and I told Kim-Dung to book the next day’s Pan Am flight. The operation had really whacked me out.

Heavily-sedated, I slept through the day as my wife came and went and made travel arrangements through the AP office. Resting next to my bed on a lounge chair, she was quickly next to me as I woke up from my opiad-induced reverie during the long night. We kissed deeply and she quietly pulled the curtains closed and climbed into the hospital bed on top of me. We’d lost everything but still had each other.

The next morning, Kim-Dung was gone.